LOUISVILLE, Ky. — Louisville became the epicenter of claims of racial injustice in law enforcement on March 13, 2020, when 26-year-old Breonna Taylor was shot and killed by police officers serving a no-knock warrant at her home.

Hundreds of thousands of marchers protested in Louisville during the summer months. Curfews were set, people were injured and arrested. Celebrities and athletes joined the calls for the officers to be arrested as Kentucky Attorney General Daniel Cameron and a grand jury took center stage in the aftermath.

Spectrum News 1 is offering a retrospective of the events, activism and reaction that have taken place over the year. We encourage you to watch our special, March Toward Racial Equality in Louisville above.

We have also broken down the segments into the following stories.

- Breonna Taylor's Case

- Protesters Reflect on Their Experiences

- The Progress with No-Knock Warrants

- The Fight for Racial Justice

Breonna Taylor's Case

It has been one year since Taylor’s death.

Wanton endangerment charges were filed against the former Louisville Metro Police Department officer Brett Hankison Sept. 23, 2020, in the March 2020 shooting that led to the death of Taylor.

Jefferson County Circuit Judge Annie O’Connell announced the findings of the Jefferson County Grand Jury. Three counts of first-degree wanton endangerment for Hankison -- none of those charges involve shooting Taylor, but are related to shots fired into neighboring apartments.

None of the officers face charges in connection with the death of Taylor.

The officers, who were not in uniform, were executing a no-knock search warrant at Taylor’s Louisville apartment for suspected drug activity. Taylor’s boyfriend, Kenneth Walker, and the LMPD officers exchanged gunfire. Walker said he believed the officers were intruders. The LMPD officers fired more than 20 shots, eight of which struck Taylor. LMPD Sgt. Jonathan Mattingly was injured by gunfire. No drugs were found in Taylor’s apartment.

Taylor was not the main suspect in the case, but was named on the warrant. Detectives said they witnessed the main suspect, Jamarcus Glover, arrive at Taylor’s apartment in January, go inside, and exit with a package. Police said Glover then got into his car and drove to an address that was a “known drug house,” according to public records.

Walker told police he and Taylor were in bed watching a movie when police began knocking on the apartment door. He grabbed his gun around the time the officers used a battering ram to break open the door and enter the apartment, at which time he fired one shot without knowing the men were police officers, he said.

Mattingly was shot in the leg and said in an interview he returned six shots. It was reported LMPD officer Myles Cosgrove fired shots from inside the apartment, and Hankison fired 10 shots from a patio outside the apartment, according to Hankison’s termination letter. Walker said when the shooting ceased, Taylor was on the ground bleeding.

Attorneys for Taylor's family claim 120 LMPD officers went to the complex in the hours after the shoting, but no one went into the apartment to provide aid to Taylor until Walker surrendered, according to the timeline. SWAT moved into the apartment after Walker surrendered to police and found Taylor unresponsive on the hallway floor.

Walker was taken into custody at the scene and driven to LMPD headquarters, where he was interrogated until around 5:30 a.m. He said he asked officers “a million times” during the interrogation why they were knocking on Taylor’s door and “no one had an answer.”

Walker, who was licensed to carry a firearm, was initially charged with the attempted murder of a police officer, but those charges were later dismissed.

The LMPD officers involved in the shooting were placed on administrative reassignment pending the outcome of an investigation by the department’s internal Professional Integrity Unit. The investigation’s findings were given to Kentucky Attorney General Daniel Cameron on May 20 to determine if any of the officers should be charged. Louisville Mayor Greg Fischer requested the FBI and U.S. Attorney’s Office review the findings. The FBI’s Louisville Field Office announced on May 21 it would also conduct an investigation. There is no body camera footage of the raid.

Officials Weigh In

Gov. Andy Beshear on May 13 responded to reports about Taylor’s death and said the public deserved to know everything about the raid. Beshear requested Cameron and local and federal prosecutors review the Louisville police’s initial investigation “to ensure justice is done at a time when many are concerned that justice is not blind.”

Fischer in early June called for Hankison to be removed from the Louisville Police Merit Board, which reviews appeals from police in disciplinary matters. Three months after Taylor’s death, Louisville Metro Police Interim Chief Robert Schroeder sent Hankison a letter stating termination proceedings against him had begun.

The letter said Hankison had violated departmental policies on using deadly force by “wantonly and blindly” firing into Taylor’s apartment without determining whether any person presented “an immediate threat” and if there were “any innocent persons present.” The letter also cited past disciplinary action taken against Hankison by the department, including for reckless conduct. Hankison was fired on June 23 and has appealed his termination. A hearing for the case has been delayed, pending the completion of the criminal investigation.

AG Meets With Taylor Family

On Aug. 12, 2020, Cameron and Taylor’s family, attorneys, and local community activist Christopher 2X from the Game Changers organization met to discuss the case.

Taylor’s mother, Tamika Palmer, was optimistic after the meeting.

“I’m glad the attorney general asked for this meeting,” Palmer said. “He actually seemed sincere and genuine, which I appreciated. We let him know how important it was for their office to get all the facts, to get the truth, and to get justice for Breonna. We all deserve to know the whole truth behind what happened to my daughter. The attorney general committed to getting us the truth. We’re going to hold him up to that commitment. At the end of the day, we have to bridge the community and the police. That starts with the truth and justice. And, we have to make real changes to keep this from happening to anyone else. The attorney general didn’t say which direction he’s pointing to, and I could be wrong, but after meeting him today, I’m more confident that the truth will come out and that justice will be served.”

Taylor’s Family Files Wrongful Death Suit

Taylor’s family filed a wrongful death lawsuit on May 15. It states, among other things, Taylor and Walker thought their home had been broken into by criminals and “they were in significant, imminent danger.” The lawsuit alleges, “the officers then entered Breonna’s home without knocking and without announcing themselves as police officers. The defendants then proceeded to spray gunfire into the residence with a total disregard for the value of human life.”

Photos were released to the public on May 14 in The Courier-Journal by Taylor family attorney Sam Aguiar that show bullet damage in her apartment and the apartment next door.

Louisville Police Chief Steve Conrad announced his retirement May 21 after local and national criticism for the department’s handling of the case. Conrad was fired on June 1 after the fatal shooting of Black business owner David McAtee.

Fischer suspended the use of no-knock warrants on May 29 and it was announced on June 10 the LMPD would require all sworn officers to wear body cameras. The LMPD is also changing how search warrants are executed.

Protests

For months after the shooting, Taylor’s family, members of the community and protesters worldwide demanded the officers be fired and criminally charged. Protesters outside Fischer’s office on May 26 demanded the officers be arrested and charged with murder. Around 600 demonstrators marched May 28 in downtown Louisville, chanting, “No justice, no peace, prosecute police” and “Breonna, Breonna, Breonna.”

More than 100 people participated in the Youth March for Freedom on July 4 in downtown Louisville. The participants stopped at historic civil rights sites, and speakers called for an end to racial injustice and told the stories of the people affiliated with those sites.

The national social justice organization Until Freedom organized a march on July 14 of more than 100 people to Cameron’s house, where protesters occupied his lawn, demanding charges against the officers involved in the killing. Nearly 90 protesters were arrested and removed from the lawn.

Around 300 members of the Atlanta-based Black militia Not F—ing Around Coalition (NFAC) marched in Louisville on July 25 while the street was lined with local protesters. John “Grandmaster Jay” Johnson, the founder of the NFAC, gave a speech calling on officials to speed up and be more transparent about the investigation into Taylor’s death.

As of Aug. 10, LMPD officers had arrested 500 protestors over 75 days.

A four-month delay, a lack of fans, and Authentic's win against favorite Tiz the Law likely won't be the things people remember about this year's 146th Kentucky Derby as protests took place throughout Louisville on Derby Day in September, including outside and around Churchill Downs by multiple groups demanding justice for Taylor.

Sept. 13, marked the six-month anniversary of Taylor’s death. Members of the Kentucky Alliance Against Racist And Political Repression had a press conference that day calling for Louisville city and police leaders to address issues they have related to Taylor’s death.

On Sept. 23, the day of the grand jury announcement, two Louisville Metro police officers were shot during protests after the lack of charges against the officers involved in Taylor’s death. Officers were called at about 8:30 p.m. the evening of Sept. 23 to a large crowd in the area, where the two officers were shot. The injured officers were taken to University Hospital. One officer had surgery and both officers, who were not identified at the time, sustained non-life-threatening injuries, Interim Police Chief Robert Schroeder said. During a brief news conference the night of the shooting, Schroeder described the incident.

"I'm very concerned about the safety of our officers. Obviously, we've had two officers shot tonight and that is very serious. It's a very dangerous condition. I think the safety of our officers and the community we serve is of the utmost importance," he said. One person has been taken into custody. That person has not been identified.

Family Calls Out Prosecutor

Glover, Taylor’s former boyfriend, faced drug charges stemming from the case involving the search warrant of Taylor's home, and incidents leading up to April 22.

A plea deal for drug charges for Glover from March and April incidents was released by the Commonwealth's Attorney after the attorney for Taylor's estate took to social media to accuse the prosecutor of trying to name Taylor as a co-defendant and indict her in July, long after she died.

In a post on attorney Sam Aguiar's personal Facebook page, he wrote that a July plea deal names Taylor as a co-defendant of Glover's. Aguiar said, “Breonna Taylor is not a ‘co-defendant’ in a criminal case. She’s dead. Way to try and attack a woman when she’s not even here to defend herself.”

After that, Commonwealth’s Attorney Tom Wine released a copy of the plea deal he said was official, which did not involve Taylor. Wine says the document shown by Aguiar in his post was not an official court document and was a draft and part of pre-indictment plea negotiations between Glover and his attorney.

Kenneth Walker’s Breaks Silence In Lawsuit

Kenneth Walker stepped into the public eye on Sept. 1 after filing a lawsuit against Louisville Metro Government and the Louisville Metro Police Department more than five months after Taylor was killed by police.

Walker, who was with Taylor the night she died, was initially charged with the attempted murder of an officer after police burst through Taylor’s door.

“The charges brought against me were meant to silence me and cover up Breonna’s murder," Walker read from a prepared statement on the steps of Metro Hall. “For her and those that I love, I can no longer remain silent.”

Walker was surrounded by his parents and two attorneys, Steven Romines and Frederick Moore.

“Kenny had never been in trouble in his life,” Romines said as Walker’s mother nodded in agreement. “And the police want you to believe that at almost 1 a.m. one evening he says, ‘My first foray into the criminal justice world, I’m gonna try and shoot a cop.’ It's a ridiculous position.”

Romines and Walker claim Walker and more than a dozen neighbors never heard plain-clothes LMPD officers identify themselves or give any warning before breaking into Taylor’s Louisville home. Testimony from multiple officers who executed the now-banned no-knock warrant claim they did announce themselves to whoever was inside.

Walker can be heard on a 911 call sobbing as he spoke with a dispatcher after the incident.

“I don’t know what’s happening. Someone kicked in the door and shot my girlfriend,” he said on the recording.

At the press conference announcing the lawsuit, Walker recounted that night.

“Breonna and I did not know who was banging on the door, but the police know what they did.”

In the lawsuit, attorneys cite alleged mismanagement, abuse, and improper interrogation carried out by LMPD detectives. They also pointed out a post signed by Ryan Nichols, president of the River City Fraternal Order of Police, to the order's Facebook page dated March 27.

At that time, Walker was still charged with the attempted murder of an officer and had just been released to house arrest – as hundreds of other inmates had either been moved or had their sentences commuted – to help stop the spread of COVID-19. In the post, Nichols condemned Judge Olu Stevens for allowing Walker to move home, writing, “This man violently attacked officers ... Not only is he a threat to the men and women of law enforcement, but he also poses a significant danger to the community we protect!”

Walker requested the court declare:

- He lawfully stood his ground when he fired a single shot at the doorway, believing an intruder was entering the home;

- He cannot be charged any further for what happened the night of the shooting;

- The metro government is not immune from liability; and

- He is owed compensation.

Neither the court filing nor Walker’s attorneys disclosed what they are seeking for compensation.

Tayor's Family, City Reach Settlement

Taylor’s family and the city of Louisville reached a $12 million settlement that also includes several police-reform measures, Mayor Greg Fischer announced at a Sept. 15 press conference where lawyers for the family and Taylor’s mother also spoke.

“As significant as today is, it’s only the beginning of getting full justice for Breonna,” said Palmer. “It’s time to move forward with the criminal charges because she deserves that and much more. Her beautiful spirit and personality is working through all of us on the ground, so please continue to say her name: Breonna Taylor.”

Along with the monetary settlement, among the largest ever paid out for someone killed by police, the settlement includes several police-reform measures that Fischer said, “are needed to prevent a tragedy like this from ever happening again.”

The reforms include a requirement that a commanding officer approves all search warrants, new programs to incentivize police officers to live where they work, and a commitment to send social workers out on calls with police officers, when appropriate.

The city will also put in place a new system to monitor officer behavior and has pledged to include random drug testing of officers in its next contract with the FOP. The LMPD declined to comment on the reforms and the River City FOP did not return a request for comment.

Lonita Baker, an attorney for Taylor’s family, said that the settlement was “non-negotiable” without police reforms.

“It’s important for her family that they minimize the risk of what happened to Breonna Taylor happening to any other family in Louisville, Kentucky and we’re going to continue that fight beyond the city of Louisville, Kentucky and through this county,” Baker said.

Taylor’s family filed a wrongful death suit in late April. It accused Louisville police of failing to identify themselves before entering Taylor’s South Louisville apartment early on March 13. Taylor’s boyfriend, who later said he thought an intruder was entering the home, shot once, hitting Sgt. Jonathan Mattingly in the leg. Mattingly and two other officers — Myles Cosgrove and Brett Hankinson — then “proceeded to spray gunfire into the residence with a total disregard for the value of human life,” the lawsuit said.

The $12 million settlement is the largest the city has ever paid out, surpassing the $8.5 million paid to Edwin Chandler in 2012. Chandler served more than nine years in prison for a murder he didn’t commit. In June, former LMPD Det. Mark Handy pleaded guilty to perjury for his testimony that helped convict Chandler.

Oprah, Professional Sports Teams Weigh In On Case

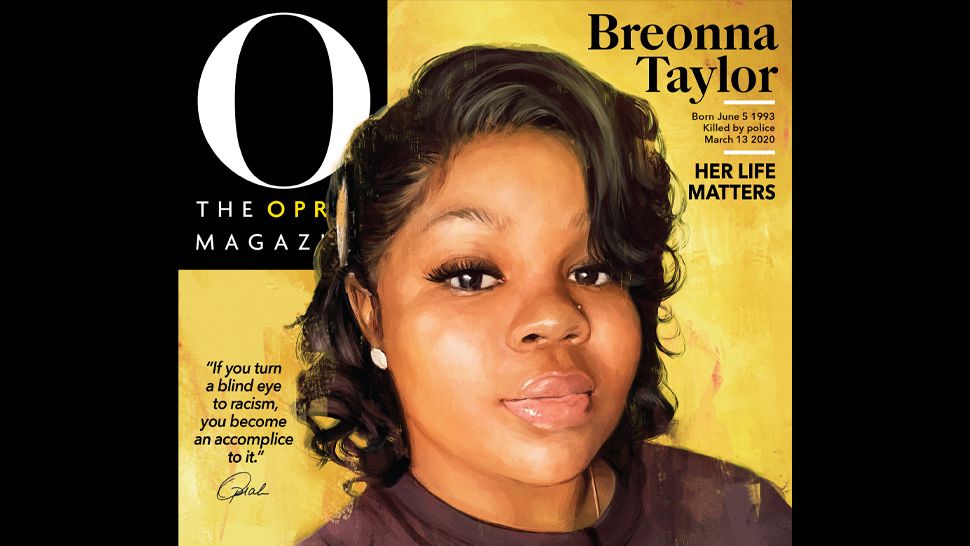

The September 2020 edition of “O” magazine featured Taylor on the cover instead of the usual image of Oprah Winfrey as a way to honor “her life and the life of every other Black woman whose life has been taken too soon.” It was the first issue in the magazine’s 20-year history that did not have Winfrey’s image on the cover. Twenty-six billboards – one for every year of Taylor’s life – were put up around Louisville paid for by Until Freedom and "O" magazine. Winfrey released a video 150 days after Taylor’ s death calling for the officers to be arrested.

Several professional sports teams and individual athletes are honoring Taylor. Before the 2019-20 NBA season restarted, the Memphis Grizzlies wore shirts with Taylor’s name and “#SayHerName” as they arrived at the arena.

Reaction to the Grand Jury Decision

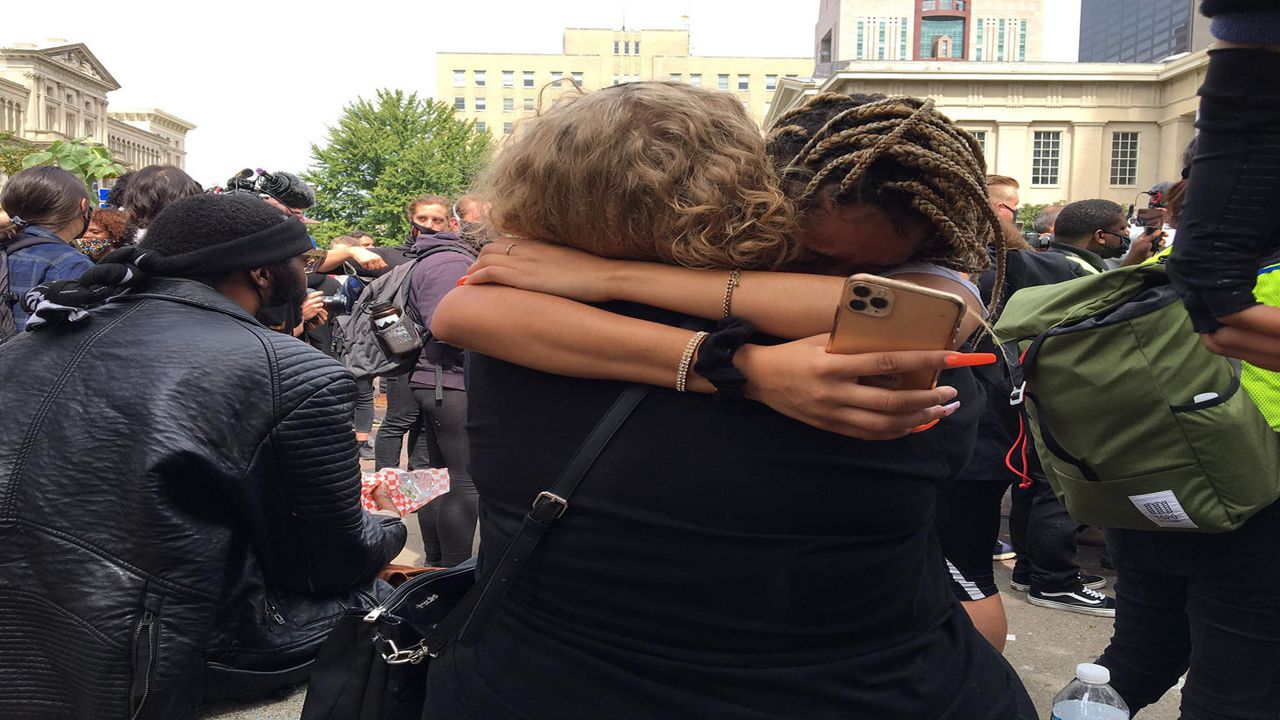

A crowd gathered at Jefferson Square Park on Sept. 23 in anticipation of the historic grand jury announcement. Once the indictment in the Taylor case was handed down, there was grief and outrage. People hugged, cried, shouted, and stomped. Hankison was the only one indicted, charged with three counts of wanton endangerment.

Kentucky’s congressional delegation also reacted to the decision.

"The grand jury does its job. The judicial system does its job. Our job here is to make sure that we advocate for police reform that addresses legitimate grievances from the African-American community while at the same time supporting community policing and responsible policing," said Rep. Andy Barr, R-KY.

Members of Kentucky's Congressional delegation were measured in their reaction as they said they wanted more time to look at the indictment before offering a lengthy response.

When asked if federal police reform would quell the civil unrest witnessed across the country, Rep. Thomas Massie, R-KY, said, "The police are regulated by the states and the police report to the mayor so it's really not Congress' place to tell the mayor of Louisville how to run the police."

As the calls for equity and fairness continue, federal police-reform efforts have stalled. That’s due in part to disagreement on the core issue of what contributes to disproportionate police violence in communities of color. Many Republicans maintain it's an issue of a few bad actors in law-enforcement, while Democrats like Congressman John Yarmuth, of Louisville, recognize recent episodes as linked to systemic racism.

"Congress is only one small piece in society of what needs to be done to address systemic racism. It's something that pervades our police forces. It pervades our business world. It pervades our education system. There are a lot of people that are going to have to work together to finally deal with the systemic racism in this country," said Yarmuth.

Taylor's family spoke publicly for the first time on Sept. 25, after the grand jury announced its findings in the case emotionally demanding that the transcripts for the proceedings be released. Attorneys Ben Crump, Sam Aguiar, and Lonita Baker joined Taylor’s family in Jefferson Square Park that morning asking for the same. Protests the night before were largely peaceful.

Some members of Breonna’s family, including her mother, have taken to social media. On Instagram the day before speaking publicly, Palmer wrote, "It's still Breonna Taylor for me," followed by the hashtag #ThesystemfailedBreonna.

Taylor’s family and an anonymous grand juror also called on Cameron to release the transcripts of the grand jury testimonies. Jefferson County Circuit Court Judge Ann Bailey Smith ordered Cameron to release them on Sept. 29. The 15 hours of recordings were released on Oct. 2.

A Kentucky man who served on the grand jury said on Oct. 28 he felt police actions on the night of her death were “criminal,” but grand jurors were not given the chance to explore charges related to her shooting death by officers.

Two grand jurors, one a white man and one Black man, spoke out about the grand jury proceedings through statements, but have remained anonymous.

LMPD Sgt. Jonathan Mattingly, who shot during the deadly raid at Taylor’s apartment, filed a lawsuit in October against Walker claiming he is a victim of emotional distress.

The civil suit claims Mattingly "experienced severe trauma, mental anguish, and emotional distress" because of Walker’s actions, when he fired a shot that night, hitting Mattingly in the leg. Mattingly is seeking a jury trial and damages.

In December, a request by Palmer for the appointment of a new prosecutor in her daughter’s case was denied by the Kentucky Prosecutors Advisory Council (PAC), which said that it doesn’t have the authority to make such an appointment.

“The attorney general is the chief law enforcement officer of the Commonwealth of Kentucky and the Prosecutors Advisory Council's duties and responsibilities, as authorized under Kentucky law, simply do not allow for the Prosecutors Advisory Council to usurp the authority of the attorney general,” Christopher T. Cohron, the Commonwealth's Attorney for the Eighth Judicial Circuit and a member of the council, said at the meeting. “Quite simply put we do not have the legal authority to fulfill the request that has been submitted.”

The Officers Involved

Hankison was arraigned at 3:30 p.m. on Sept. 28 and entered a plea of not guilty to the three counts of wanton endangerment.

During Hankison's pre-trial conference on Oct. 28, Bailey Smith heard arguments about whether the court should reverse its order to place discovery for the case into the court file.

Ahead of the conference, the Kentucky Attorney General's Office, along with Hankison's attorney, Stewart Matthews, asked the court to reconsider its decision and instead keep the discovery sealed. The Courier-Journal, represented by attorney Michael Abate, motioned to intervene.

Hankison’s trial is set to begin on Aug. 21, 2021.

The LMPD on Tuesday, Dec. 30, issued a termination letter to Detective Joshua Jaynes, saying he violated two department standards when he lied on a search warrant used to raid Taylor's apartment. Cosgrove also received a pre-termination letter. Those two officers were officially fired on Jan. 6, 2021.

LMPD Major Kimberly Burbrink, who oversaw the officers involved in the raid of Taylor’s apartment, was demoted and reassigned by the new LMPD Chief Erika Shields.

Looking Ahead

The chants demanding justice for Taylor continue and the work of family members, activists, lawyers, and lawmakers show no sign of stopping.

Cameron has launched a review of Kentucky's search warrant process and a petition calling for his impeachment was filed in January as a result of his handling of the Taylor case. A bill to significantly limit when no-knock warrants can be issued cleared the Kentucky Senate unanimously in late February -- many criminal justice reform advocates called for a ban on such warrants after Taylor's death.

The Speed Art Museum announced its next exhibition, titled "Promise, Witness, Remembrance," will reflect on the life of Taylor, her death, and the protests that gripped Louisville over the summer. The exhibit will open to the public April 7 through June 6.

"The exhibition explores the dualities between a personal, local story and the nation's reflection on the promise, witness, and remembrance of too many Black lives lost to gun violence," according to a release from the museum.

Members of a "Breonna's Law" caravan went to the state capitol in Frankfort on March 3 to demand the legislature pass House Bill 21 into law. The bill has not been addressed since being filed on Aug. 13, 2020, by state Rep. Attica Scott, a Democrat from Louisville.

Protesters Reflect on Their Experiences During Summer Protests

- Watch Khyati Patel's story with four protesters who share their experiences

- The Progress with No-Knock Warrants

- The Fight for Racial Justice

LOUISVILLE, Ky. — Jefferson Square Park became the epicenter of the movement to call for justice for Breonna Taylor. She died on March 13, 2020, at the age of 26.

Hundreds of thousands of marchers took over downtown Louisville during the summer months. Curfews were set, people were hurt and arrested and at the heart of it, all protesters were heard.

One year later, we are speaking with four protesters who share their journey.

Night after night, the intense and sometimes shocking scenes caught on camera and broadcast live around the world unfolded on Louisville streets.

“It is lightweight traumatic to have to sift through all those memories to try to figure out which day to talk about because they weren't all good. They weren't all bad. Some days were graded. Some days both had good and bad,” said Carmen M. Jones, a 24-year-old protester.

Jones was there on day one and is among the first to call Jefferson Square Park home. She has the scars to prove it.

“I remember one time we were standing under the helicopter and the helicopter was inches from us like it was pretty low to the ground, and they deployed the tear gas and I still got the chemical burn of my neck. from the tear gas and it bothers me every now and then like, because like, it'll never be washed out of my skin, you know what I mean,” Jones said.

Blu Lewis, 24, rendered first aid during the demonstrations. In the protests, Lewis said she helped at least 10 people from passing out in one afternoon.

“People having anxiety attacks. ambulances had to be called. I was a street medic so I’m rushing to everyone, I’m checking people’s vitals, I’m trying to calm people down, get people’s eyes from rolling to the back of their head you know,” Lewis said.

Shaela Worsley, 20, said she took off work to march for justice and went back to her hometown of Richmond to spread the same message of "no justice no peace.”

“She should not have her, her life should not have ended that quickly. She had so much going for herself, you know. She wished for so much and it's sad that her dreams were cut short that her goals were cut short,” Worsley said.

She added, “We have to fight so much harder just to be heard, so they can just even see us."

By the end of September, Kentucky Attorney General Daniel Cameron released the much-awaited decision about charges in the death of Taylor.

“Of wanton endangerment for wantonly placing the three individuals in apartment three in danger of serious physical injury or death,” Cameron said on September 23, 2020.

Louisville erupted.

“Everyone was out here, you know, watching it on their phones and stuff and listening into, you know, see what the news was going to be. That hit home that that really made us like we physically felt that,” Lewis said.

Pastor Tim Findely Jr. of the Kingdom Fellowship Christian Life Center shared his reaction to Cameron’s decision.

“When they essentially said that concludes today, it was an absolute shock. That shock went to grief and sadness which immediately gave way to anger. It's one of those days that I'll never forget. I'll never forget that moment, that it felt crushing. It felt hurtful,” Findley said.

He said that moment reaffirmed his commitment to the fight for justice.

“I think we as people have to realize the power of unrest, the power of protest, it doesn’t stop there because there has to be a pivot from protest to policy. But there is power in the collective voice of individuals coming together and putting demand on government, putting demand on officials but there has to be change,” Findley said.

He remains an outspoken agent for change.

“Last year 2020 was about bringing a spotlight to the inequities in our criminal justice system here in Kentucky,” Findley said.

Findley’s message to his large following in Louisville is consistent.

“Don't stop protesting. Don't stop demanding. Don't stop demonstrating. Don't stop highlighting what's going on. But you’ve got to get to the table,” Findley said.

For now, the chants continue and the work for these protesters will not stop.

“You know, we still need our voices to be heard, we still need to fight for Ms. Breonna Taylor, you know it might just be a year later, but she's still gone. You know she was still someone's child. She was still someone's friend, but most importantly, she was still a person,” Worsley said.

The No-Knock Warrant: Progress Still Being Made One Year After Breonna Taylor

- Watch Ashleigh Mills' story abut the state of No-Knock warrants in Kentucky

- The Fight for Racial Justice

LOUISVILLE, Ky. — One year since that fateful morning when the Louisville Metro Police detectives killed Breonna Taylor, protest ensued, and a national spotlight was put on the no-knock warrant. For years, no-knock warrants allowed police to make quicker entries without announcing or knocking, during raids.

Even one former Louisville Metro Police Department (LMPD) officer scrutinized how officers carried out the raid on Taylor’s apartment.

"It’s hard to second guess those officers,” retired officer Andre Bottoms admits. He explains how he claims his platoon could have handled it, based on how they usually served warrants.

“We tried to limit the warrants we did at night, do ‘em a lot earlier. We watched ‘em, and grab ‘em, and take the key and go back and open the door, you know, with them -- catch them coming and going. You know, and hindsight is 20/20," Bottoms offers.

In Taylor’s case, LMPD and Kentucky Attorney General Daniel Cameron maintain the warrant was not served aKs a no-knock.

“Evidence shows that officers both knocked and announced their presence at the apartment,” Cameron said during his September 2020 press conference to announce the grand jury’s decision. It did not indict three officers involved in Taylor’s death.

When questioned in May by the LMPD Public Integrity Unit, Sgt. Jon Mattingly said, "I knocked on the door. (I) banged on it. We did announce the first couple because our intent was not to hit the door."

However, in police recordings, some neighbors cast doubt on that. One witness said, “No. Nobody ever identified themselves."

Another, said, "Nothing was said, that they just beat on the door."

The identities of the witnesses have been kept confidential by police.

In June, Louisville Metro Council responded unanimously, banning no-knock warrants in the city, in the landmark ordinance called "Breonna’s Law." The state is considering a statewide mandate.

State Representative Attica Scott (D) has a bill with the same name, which is House Bill 21 (HB 21) The name, "Breonna’s Law," is important to her.

“It will be the first time in the history of the Commonwealth of Kentucky that a piece of legislation would carry the name of a Black woman," Scott remarks.

However, another piece of legislation that made more progress than hers has: Senate President Robert Stivers’ bill, Senate Bill 4 (SB 4), made quick progress through the Senate.

When asked why Stivers' bill progressed further than hers, Scott said, “I understand institutional systemic racism and how it works, and the legislative body is no exemption to that reality.”

Stivers' said, “It wasn’t anything intentional or unintentional. Well, I guess it’d be unintentional. This was a thought process that I had formed over years of practice and years of experience here. There was nothing about it that was intentional. It was just (what) I was bringing to the table and what I felt I could do discussing with other individuals about the bill.”

There are some key differences between the early versions of the two pieces of legislation. Each bill would restrict the no-knock warrant, and require officers doing search warrants to wear body cameras.

The early version of HB 21:

- Requires police wait at least 10 seconds after knocking, before forcing in

- Requires police activate body cameras at least five minutes before and after the warrant

- Require drug and alcohol tests for officers involved in deadly encounters

On the notice, it provides people within the house or apartment, Scott said, "within 10 seconds you can get into that house or that apartment and get to someone before they flush (evidence) down the toilet."

There are some exemptions to knocking and announcing in Stivers’ early version.

The early version of SB 4 requires no warrant for entry without notice, unless:

- Responding to a violent crime

- Knocking and announcing could endanger a person’s life

- Knocking and announcing could allow the person inside to destroy evidence to implicate them in a violent crime

There’s now no chance of Scott’s Breonna’s Law passing. It’s too late in the legislative session, and the bill didn’t get far enough. However, there is a chance of Stivers’ bill passing. It could get some of those things from Scott’s version added to it.

Attorney Ted Shouse works in criminal justice and has volunteered to do pro bono help with The Bail Project in Louisville. The Bail Project offers free bail assistance to thousands of low-income people. Shouse has helped bail out protesters in last summer's protests including Rep. Scott.

Shouse feels those exceptions in Stivers’ version, though, render the bill useless.

“If you’re always concerned about the destruction of evidence, then you're always going to have an exception to the rule,” said Shouse. “Bottom line is, that Sen. Stivers' bill flew through the Senate, and Representative Scott's bill languished."

He believes Scott deserved more of a chance than her legislation had. But Shouse is hoping for change beyond banning the no-knock statewide.

“Obviously, the problems are systemic, but it’s how entrenched they are. So when you suggest even these minimal reforms, the push back is tremendous,” Shouse regrets.

He wants the entire search warrant process to be overhauled. That includes changes to how judges approve search warrants.

“As I’ve said publicly before, if I could pick the judge for every single one of my cases, I would. I don’t get to do that. My judges are randomly assigned,” Shouse said.

He wants judges randomly assigned for approval or disapproval of search warrants, instead of officers choosing. He also wants records kept of when a judge denies a warrant.

Meanwhile, Louisville has seen some change. As part of the $12 million settlement between Taylor’s family and the city, warrants now must be approved first by a commanding officer at LMPD. There’s also a new form to submit them through. The people pushing change are hoping that the officers are following this.

A Year After Breonna Taylor's Killing, the Fight for Racial Justice Continues

LOUISVILLE, Ky. — At the start of last summer’s protests against the police killing of Breonna Taylor, the list of demands made by those resisting in Louisville’s streets was short enough to fit into a hashtag: #JusticeforBreonnaTaylor.

As the summer went on, the scope of their demands grew. Along with pleading for a direct response to Taylor’s death at the hands of the Louisville Metro Police Department (LMPD), activists and organizers began discussing a fundamental restructuring of police, economic justice for historically marginalized groups, and other steps on the road to racial equity in Louisville.

Last June, the Louisville Metro Council enacted a tangible, policy-based response to Taylor’s killing when it passed a ban on no-knock warrants. The city later established a civilian review board for its police department and agreed to a series of police reforms in a $12 million settlement with Taylor’s family.

But upon the one-year anniversary of Taylor’s killing, the fight is far from over, local Black leaders told Spectrum News 1. Reforms in direct response to Taylor’s killing are still needed, they said, along with broader efforts to reduce inequity for the 150,000 Black people who call Louisville home.

“There has to be a complete tearing down of this racist structure and building something that’s equitable for everyone,” said Pastor Timothy Findley of Louisville’s Kingdom Fellowship Church. An active participant in the summer protests, Findley said addressing racism and racial inequities requires more than police reform.

“It's housing,” he said. “It's education. It’s poverty. I say all that to say, it’s the structure.”

Justice for Breonna

One year later, the response to Taylor's killing is not yet complete. The FBI is still investigating the possibility of civil rights violations as well as the process of obtaining the search warrant on her home. And many Louisvillians are still waiting for justice, Louisville Urban League CEO Sadiqa Reynolds said. She pointed out that no one involved in Taylor’s killing has faced criminal consequences for her death.

“Justice is very slow when it comes, if it comes at all,” she said. “That’s a real challenge for our entire community."

Detective Brett Hankison is the only officer who was charged in connection with Taylor's killing. He will go on trial this summer on three counts of wanton endangerment stemming from shots he fired the night of Taylor's death. The charges, however, relate to bullets that entered other apartments, not Taylor's.

While a host of policy changes have been proposed in response to Taylor’s killing, including a statewide ban on no-knock warrants, only a few have actually been implemented.

The settlement between Taylor’s family and the city of Louisville included several police reform provisions, including measures to ensure a commanding officer approves all search warrants, new programs to incentivize police officers to live where they work, and a commitment to send social workers out on calls with police officers, when appropriate. A short-term police contract approved late last summer, included only one of these.

State Representative Attica Scott has introduced Breonna’s Law, which would ban no-knock warrants in Kentucky and institute several other police reform measures. After months without action, the House Judiciary Committee announced plans last week to give the bill a hearing before the end of the legislative session. It’s passage appears unlikely.

In addition to her own law, Scott said there are other measures that she would like to see become law in response to last summer’s protests. “We shouldn’t be militarizing police against their neighbors,” she said. “We shouldn't have police targeting live streamers.’

Referencing her own arrest during the protests, which lead to her being charged with felony rioting, she said, “We need to clearly define clearly in statute what we mean by riot.”

But Scott also said the mission is much bigger. “We have to address economic and social issues. Pay people a living wage. Address the fact that Black women are three to four times more likely to die in childbirth than white women. Address education equity. There’s so much more that we have to do that is beyond policing, but policing has to be addressed because we’re paying people to murder us."

The many forms of justice

At Broadway and Preston Street, Kingdom Fellowship Church is a little over a mile away from Jefferson Square Park, the epicenter of Louisvlle’s protests last summer. Pastor Tim Findley knows the path between the two sites well.

Last summer, he hosted press conferences, provided parking and shuttles to protests, and was even arrested in the streets. Months later, he told Spectrum News 1 that the work he is engaged in is about changing “more than just policing.”

“We're coming together and saying, ‘We're getting hit on every side. We're getting hit in every category. There's something that has to be done,’” Findley said. “Enough is enough. We have to have wholesale change. There has to be a complete tearing down of this racist structure and building something that's equitable for everyone.”

Findley said that will include addressing issues of inequity in housing, education, economics, and health care, which he’s gotten a first hand look at in recent weeks. “We were a vaccination site a week ago,” he said. “We had over 1,000 people come to these doors.”

When he asked those who showed up at Kingdom Fellowship for a vaccination why they hadn’t gone elsewhere, he did not hear concerns about vaccine safety, but complaints about accessing vaccination sites. “It’s been hard to get to, and we made it easy,” he said.

Economic justice has been a recent focus of the Louisville Urban League, which recently opened a 24-acre sports and learning complex in the Russell neighborhood. Reynolds said the goal is to bring more economic activity to the area, creating jobs and raising property values. The challenge, she said, is ensuring that the benefits flow to those who have called that area home for decades.

“We have the challenge of making sure that as development happens in the West End of Louisville and other poor zip codes, that the people who have really had their backs broken by policy aren't just pushed out,” Reynolds said.

Looking to the next generation

As local leaders envision a more equitable future for Black people in Louisville, they speak often of children who are currently attending underfunded public schools and living without the many advantages of their wealthy peers.

“Having a computer shouldn't be a luxury in the technology age,” Reynolds said. “We have to make sure that all of our children have those things.”

Local nonviolence activist Christopher 2X also emphasized the importance of working with young children, especially after the record number of homicides Louisville saw in 2020. The 173 homicides in Louisville last year were up substantially from the previous high of 117, set in 2016. Public health experts have struggled to pinpoint the cause of the rising violence, but some have suggested the economic distress created by the pandemic, the gun boom of 2020, and a lack of trust in police, leading people to take problems into their own hands.

2X said reversing the trend requires reaching children at a very young age. “The model of trying to do intervention by the time kids get in high school is out the door. It’s gone,” he said. Instead, his organization, is working with children under 10 to instill an early appreciation of physical safety.

“The goal is to teach them about the anatomy of the body,” he said. “Let them know about the body and the organs and then segue that conversation into discussing how, besides diseases and viruses hurting the body, gun play is hurting the body.”

Young people are also vital for turning cries for justice into practical change, as they ascend into positions of power and influence. Shameka-Parrish Wright, an organizer of protests over the summer, is running for mayor and Findley told Spectrum News 1 he will soon be sharing his intentions. Jecorey Arthur, an activist and educator who talks explicitly about working toward equity rather than equality, was elected to Metro Council last fall.

“I’m excited about the empowerment that I see and the voices that are being raised and what they’re saying,” Reynolds said. “I think that’s very important for us and I’m hopeful about our future.”

?wid=320&hei=180&$wide-bg$)