This story is part of our Climate Connections series, highlighting how a changing climate is affecting our state.

MILWAUKEE — Climate change wasn’t always the first thing on Rafael Smith’s mind.

“I always knew climate was important,” said Smith, who was born and raised in the Harambee neighborhood of Milwaukee. “But it was always a secondary issue when it comes to the immediate issues of shelter, food — those immediate needs that you have if you grow up in the inner city of Milwaukee.”

What You Need To Know

- Scientists predict Wisconsin's average temperature will rise by several degrees by the middle of the century

- Heat is already the leading cause of weather-related deaths, and experts are concerned it could become even deadlier

- Nighttime temperatures are rising especially fast, making it hard for the body to recover from hot days

- Milwaukee has some of the highest heat risk in the state, based on the urban heat island effect and vulnerable populations

These days, though, Smith believes that climate change is an immediate threat to his city. And, as the climate and equity director for Citizen Action Wisconsin, he spends a lot of time helping others see how a warmer world puts them at risk.

“I always compare it to blood pressure,” Smith said. “They call blood pressure the silent killer, because you really don’t show any symptoms of it, but it’s killing you from the inside.”

Climbing temperatures don’t just spell trouble for polar bears and icecaps. Hotter weather can have direct risks for our own health, said Caitlin Rublee, an assistant professor in the department of emergency medicine at the Medical College of Wisconsin.

Heat is already the leading cause of weather-related deaths in the United States, according to the National Weather Service. And even in a state like Wisconsin — which is better known for icy winters than burning summers — hot temperatures already send hundreds to the emergency room each year.

“We know climate change is here, and it's affecting people right now,” said Rublee, who is also on the board of directors for Wisconsin Health Professionals for Climate Action. “A lot of people talk about how it's making our planet sick. I think about how it's making our people sick.”

Since the 1950s, Wisconsin has already gotten warmer by an average of 2.1 degrees Fahrenheit, according to a report from the Wisconsin Initiative on Climate Change Impacts last year. The report estimates the state could see a rise of anywhere from 2.5 to 7.5 degrees Fahrenheit by the middle of this century, even if we lower our fossil-fuel emissions.

Those hotter temperatures spell out trouble for public health in the city — and especially for communities that are already vulnerable.

“High-heat index isn’t just a number,” Rublee said. “I hear all of the ambulance sirens, I think about all of the patients I treat, especially from specific ZIP codes within our city.”

Stressing the system

It’s easy for the human body to get stressed out when heat comes along.

To keep everything running well, your body needs to keep itself at a pretty consistent temperature, explained UW-Madison professor Jonathan Patz, director of the school’s Global Health Institute.

“We’re always trying to maintain a stable body temperature,” Patz said. “That’s important for survival, and important for brain function.”

When the outside conditions are hotter, your body has to put in more work to maintain that temperature, like by pumping more blood to the skin and producing sweat, which cools you down as the water evaporates.

And when there’s a lot of humidity in the air, that causes even more problems, since your sweat can’t evaporate easily to cool you off, Patz said.

Essentially, “heat makes your body feel like it’s running a marathon,” Rublee said. It acts as a stressor that can tire out specific organs, or the whole body — making it hard to move, think or even breathe.

When a heat wave hits the city, Rublee said doctors see some dramatic effects. People who come in with heat stroke — the highest level of heat-related illness — are “some of the sickest patients I will see in the hospital,” she said.

Even short periods of extreme heat can be devastating for communities, Rublee added. A 1995 heat wave in Milwaukee played a part in 91 residents’ deaths over 11 days, a CDC report found.

As the climate keeps changing on us, it’s likely that these kinds of extreme heat events will only become more common.

The WICCI report estimates that, by the middle of this century, we may see three times as many extremely hot days in Wisconsin. And the number of extremely hot nights is likely to quadruple in that same time period, the researchers found.

Those rising nighttime temperatures are especially concerning, said Margaret Thelen, climate and health program manager for the Wisconsin DHS. Usually, cooler nights give the body a chance to recover, but if temperatures don’t drop when the sun goes down, the body is “just constantly being stressed.”

Even though heat may not be as “flashy” as other weather events, like floods or hurricanes, Thelen said the warmer and wetter weather is a big problem for public health.

“A lot of people don't recognize when they are feeling the impacts of extreme heat,” Thelen said. “But when your body can't regulate that temperature, night after night, as the heat does not dissipate, that can be a really big danger.”

An uneven risk

People across the state may be feeling the heat in the coming decades, according to WICCI’s predictions. But some will be staring down a higher risk of health effects, especially in the Milwaukee area.

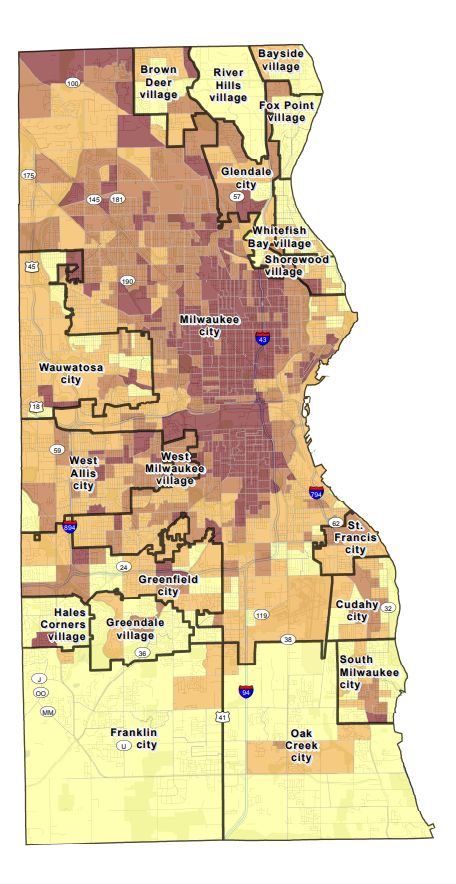

According to a Heat Vulnerability Index developed by researchers in the state, Milwaukee County is one of the most vulnerable spots for heat-related illness and death in Wisconsin. And, even within the Milwaukee area, certain neighborhoods bear a bigger burden, according to their analysis.

There are plenty of factors that lead to unequal risks from rising temperatures, Thelen said, many of which tend to be more concentrated in urban areas.

Young children, older adults and people with chronic health conditions are more sensitive to extreme heat. People who live alone might not have others checking in on them during a heat wave. Outdoor workers might not be able to cool down during the workday, and non-English speakers may not have access to important information about heat risks.

Some of that difference is also about geography: Milwaukee, like other urban areas, is subject to what’s known as the urban heat island effect.

Compared to rural areas or even suburbs — which have more greenery that uses up the sun’s energy — urban settings are full of materials that trap heat, said Elizabeth Berg, a doctoral student at UW-Madison whose research focuses on heat islands.

“Picture a grassy field — that's going to be cool overnight,” Berg said. “But an asphalt street, or parking lot that has been absorbing heat all day is going to be radiating heat upwards when the sun goes down.”

Temperatures in the city can be as much as 10 degrees Fahrenheit hotter than nearby rural areas. And the effect can create differences within a city, too, Berg said: Neighborhoods with a lot of tall buildings and paved surfaces would see a stronger heat island effect than areas with smaller houses and lots of trees overhead.

All of these factors make it hard to separate the city’s future heat risks from its historic inequities. Smith pointed to the northwest side of Milwaukee as a prime example of an area facing the heat island effect — and one where many Black residents of the city live.

“The lack of tree cover, the lack of shade, causes the temperatures in those areas of the city to be much hotter in the summertime,” Smith said. “And again, that is based on neglect.”

Historic redlining policies in Milwaukee “multiply the burden” of extreme heat, Rublee said.

A UW-Milwaukee study last year found that redlined neighborhoods still have higher rates of many health conditions, like asthma, obesity and mental illness — all of which are risk factors for heat-related illness.

And a study from local advocacy groups this year found that residents of redlined areas in Milwaukee already have a higher-energy burden, paying a bigger share of their income toward their energy bills. As temperatures rise and air conditioning needs grow, low-income families may be saddled with even bigger energy burdens, Rublee said.

For Smith, that unequal toll is an important reason to keep pushing for change.

“We’re frontline communities. We’re going to be the most impacted,” Smith said. “Poor communities of color, we don’t have money to build spaceships and go to another planet.”

Beating the heat

According to experts in Wisconsin and around the globe, there’s little question that the world will get warmer in the decades to come. But there are still ways we can protect against some of the worst effects of a hotter climate, experts said.

“I'm really optimistic,” Rublee said. “Despite a warming world and planet, my hope is that we can safeguard health and make sure people stay healthy.”

There are practical ways to prepare for extreme heat events, Thelen said. On the personal level, she recommended that people slow down, drink lots of water, know where they can go to cool down and check on their neighbors when the weather gets hot and humid.

Some urban areas of the state, including Milwaukee, have created heat task forces to prepare for extreme heat events, Thelen added. Past heat waves — like one in 2012 that led to 10 deaths in Wisconsin — were “big wake-up calls” that cities needed to have plans in place, she said.

Berg said that improving our heat advisory systems can also help people gear up for dangerously hot days.

She’s working with a team of researchers with the Wisconsin Heat Health Network on bringing other variables besides temperature and humidity into the heat wave equation. Other factors might help predict when hot conditions will be risky, she said — like looking at recent weather patterns, since “one thing that can make heat dangerous is if it’s a shock to your system.”

Of course, rising temperatures are just one piece of the climate crisis, Patz pointed out. Working to mitigate climate change as a whole — like by cutting fossil fuel emissions — is key to stopping the heat problem at its source, he said.

“What people need to realize is that, you know, you can't be can't just be mopping up the mess on the floor without thinking about turning off the faucet,” Patz said.

Smith is hopeful that moving toward a greener future can also help bring economic equity to his community.

He’s long been passionate about rebuilding the Black middle class in Milwaukee. Now, he believes that bringing green jobs like solar installation to the city can do just that.

“This is an opportunity to restore what was taken away from us,” Smith said. “So it’s not all doom and gloom.”

The human toll of a changing climate can be hard to grapple with. But advocates said those personal touches — the community members Smith meets through his organizing work, or the patients Rublee sees in her practice — keep them inspired, too.

“I think about practicing for the next 30 years, and how much death and disability I could see if we don't create these changes,” Rublee said. “And so, it really energizes me to say, 'Enough is enough. Now is the time. Let's do this.'”