MILWAUKEE (SPECTRUM NEWS) — In the 1930s, at the request of the federal government, the Home Owners’ Loan Corporation divided up America’s cities.

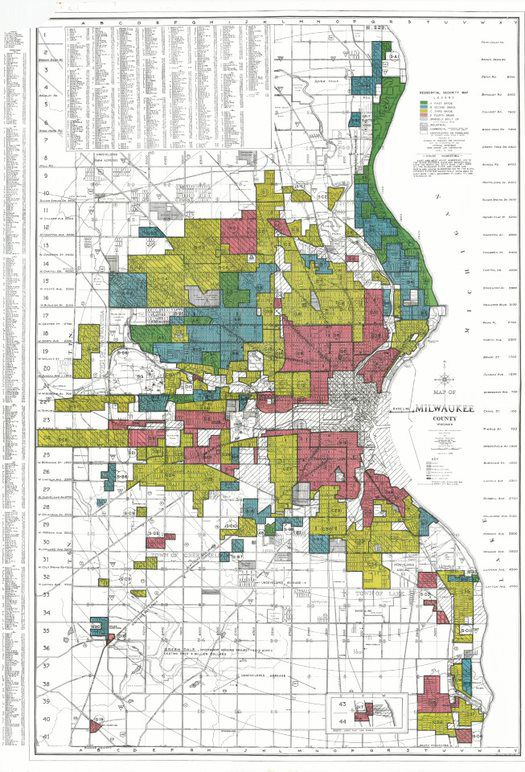

The goal was to help stabilize the housing market in the midst of the Great Depression. These HOLC maps provided a guide to where offering mortgages would be a safe bet — and which areas, shaded in red, were to be avoided.

Today, neighborhoods across the country are still feeling the consequences of that redlining process, which often relied on racial profiling to judge investment risk. And, in the midst of the COVID-19 pandemic, that decades-old red ink may be a matter of life and death, according to a recent study.

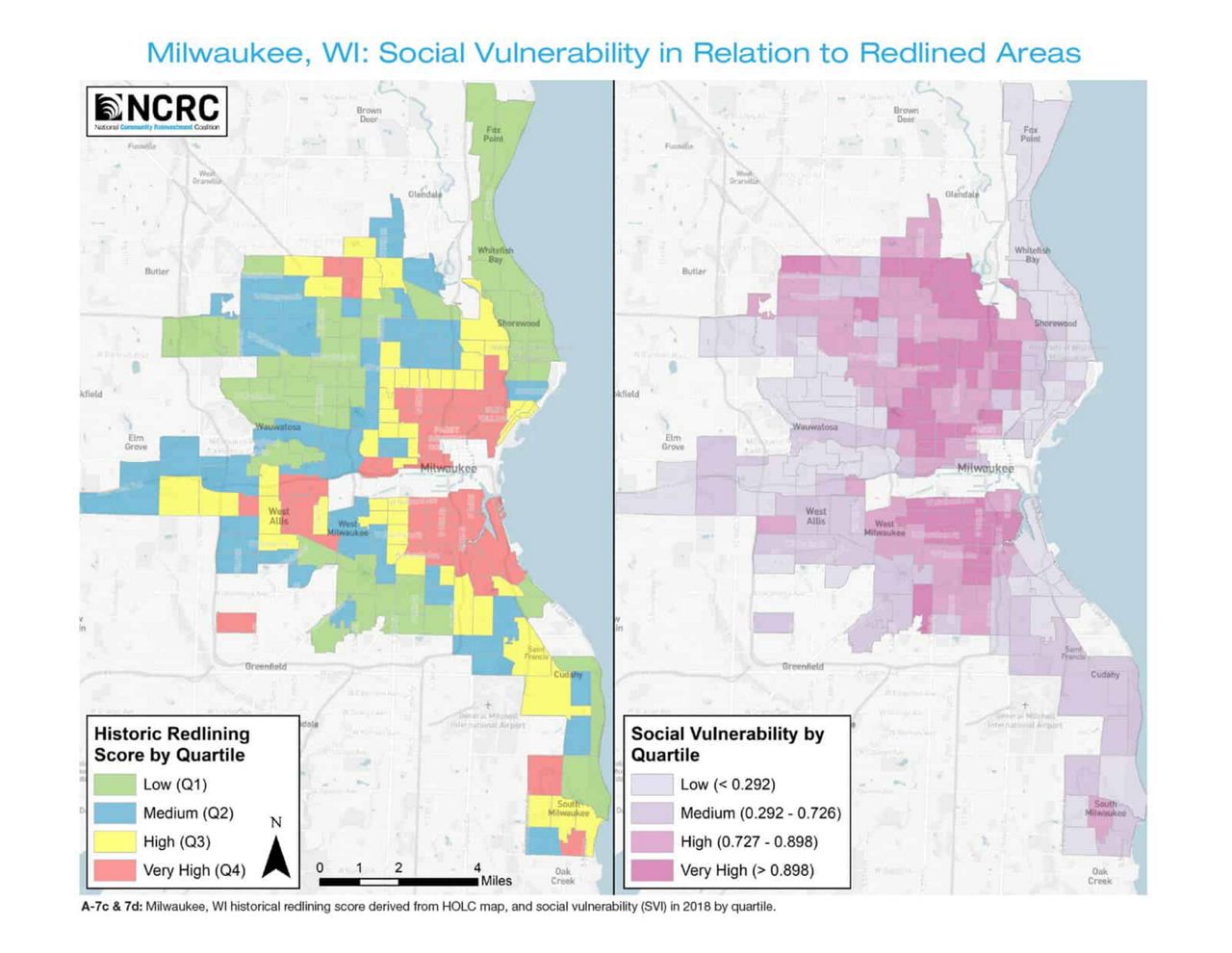

A report from the National Community Reinvestment Coalition, which included work from Wisconsin researchers, found that across the U.S., census tracts with a history of redlining were tied to worse health outcomes for residents.

“Tracts that were subject to greater redlining had higher poverty, greater social vulnerability, were more likely to be majority minority tracts,” says Helen Meier, an assistant professor of epidemiology at UW-Milwaukee who worked on the study. “We also saw associations between greater redlining and higher prevalence of chronic diseases like diabetes, COPD, and asthma.”

The findings were concerning on their own, Meier says. But they’re even more striking with the continuing threat of COVID-19, a disease that tends to hit harder when people have underlying conditions.

And for Meier, whose work has long focused on how social factors impact health, the disparity wasn’t at all surprising.

“It was utterly predictable, and horrific,” she says.

Color-coded outcomes

Though they’re now almost a century old, the HOLC maps are still highly relevant to understanding how neighborhoods compare today, the study’s authors say.

Recently, a team at the University of Richmond digitized the maps, bringing online more than 200 cities’ worth of risk analysis. The maps lay out — in bright reds, yellows, blues, and greens — the “residential security” grades assigned to various neighborhoods.

Though the maps take into account factors like building quality and location, they also frankly discuss the racial demographics of different areas. And, as the NCRC study describes, “neighborhoods in which minorities lived were almost always downgraded to the lowest of four classification grades — ‘hazardous.’”

One map’s notes describe a section of Milwaukee’s west side as a “slum area” with many Jewish and Black residents. Madison’s assessors talk about the most immigrant-heavy section as the “most troublesome area in [the] city”; in Racine, they write, “Only foreign element will buy any property in this area.”

Even after the Fair Housing Act of 1968 made it illegal to discriminate in home sales or rentals, the preconceived notions about different neighborhoods — formalized in the HOLC maps — didn’t go away, the researchers say. Lower perceptions of neighborhood value led to disinvestment and made it harder for residents to get home loans, which in turn stifled access to wealth, education, and other resources, the study’s authors write.

Today, when it comes to the struggles of many historically redlined communities, “you’re looking at the intersection of race- and place-based discrimination,” says Emily Lynch, a population health service fellow at UW-Madison who worked on the study.

Lynch, who was Meiers’ research assistant at the time of the study, says the two of them were interested in actually measuring the health effects of redlining in a quantitative way.

Because the 1930s maps don’t exactly match up with current census tracts, they averaged out the HOLC grades to create a “historical redlining score” for each tract. From there, the researchers sorted tracts from 142 cities across the U.S. into four quartiles.

They then compared social and health outcomes in the highest quartile (as in, the ones with the most redlining) to the lowest quartile (the areas with the least redlining and more favorable HOLC scores) — and the differences were stark.

On a national scale, areas with the most redlining had 28% of people living in poverty — twice as many poor residents compared to the least redlined tracts, per CDC data.

In the most redlined quartile, average life expectancy fell to 75.8 years, down from 79.4 in the least redlined quartile. And more redlined tracts faced higher rates on a slew of health conditions: asthma, diabetes, hypertension, kidney disease, obesity, stroke, and mental health issues.

The results confirmed that, almost a century later, those neighborhoods shaded in red by the HOLC still showed worse overall health outcomes. And, as the study puts it, the residents of these areas became “pockets of the population vulnerable to public health crises” — like, for example, a global pandemic.

The pandemic’s added strains

On the south side of Milwaukee, Molly Cousin says she’s seen firsthand how certain groups have to take on greater COVID-19 risks.

Cousin works as a pediatrician at Sixteenth Street Community Health Centers, which serve two of the most populous zip codes in Milwaukee County. Many of their patients are essential workers who can’t do their jobs from the safety of home; many of them also live in close quarters in multigenerational homes, where one COVID-19 infection can quickly multiply.

“That's one of the things that we've seen, and we've kind of seen from the get-go: One person in the household will get it, and then everyone in the family will get it,” Cousin says. “And then all the relatives upstairs who were trying to help out, taking care of someone, they get it.”

The neighborhoods served by Sixteenth Street have largely Hispanic residents, who make up around 16% of the population in Milwaukee County but around 24% of its COVID-19 cases, according to county data.

Similar patterns have emerged across Wisconsin and the entire U.S. as minority groups — particularly Black, Native, and Hispanic/Latino communities — have seen disproportionate impacts during the pandemic.

“COVID has just revealed existing inequities and exacerbated them,” Lynch says.

Interestingly, these racial groups that are bearing the legacy of redlining today aren’t always the same as the ones who were shut out by the HOLC maps in the first place, Lynch points out. In Milwaukee, many of the neighborhoods deemed “hazardous” were home to mostly Jewish and Eastern European immigrants in the 1930s.

But when more Black and Latino residents started moving into the city, they became the “newest, unfortunately lowest rung on the ladder,” Meiers says, and were in turn relegated to these less desirable neighborhoods. (Milwaukee’s HOLC map describes the south side as a heavily Polish area, with a growing influx of Mexican immigrants listed as a “detrimental influence.”)

In this way, while the demographics have changed, the inequities have persisted, the researchers say. Formerly redlined areas still have less access to “health promoting resources” like quality food or healthcare, while also bringing more exposure to “health damaging threats” like pollutants or, right now, infectious disease.

Cousin says at Sixteenth Street, 80% of patients are either on Medicaid or uninsured. They don’t have a “social safety net” to protect them. And the chronic stress of living in a vulnerable social position can take a toll on health too — it can even change your genes, she says.

All of these factors mean that some communities face a “double whammy” of increased COVID-19 risk, as infectious disease expert Anthony Fauci has said: They’re more likely to catch the virus, and more likely to face severe outcomes if they do.

“What COVID-19 is doing is shedding another bright light on a systemic problem that has been with us for a very long period of time,” Fauci told the American Journal of Managed Care.

Closing the gap

So, what will it take to fix these disparities? “If you know that, you win a Nobel Prize,” Meiers says.

Because there are so many factors tied up in the legacy of redlining — from housing to education to employment to wealth — there’s no easy solution to make health more equitable, she says.

And the pandemic’s toll seems to only be widening these disparities, Cousin points out. She’s especially concerned about the growing educational gaps that are leaving some minority students behind in the COVID-adapted school year.

“This is changing the outcome of what kids are going to be able to do in the future for the rest of their lives,” Cousin says. “And that's just terrible. It's just really frustrating.”

Lynch says the study highlights the need to invest in communities of color that were denied the opportunity to build wealth — since, as Meiers says, “we know that wealth and health are just inextricably linked.”

In the current COVID-19 crisis, some experts have also singled out vaccine distribution as a way to help the communities that have been hit hardest.

An expert panel from the National Academies recommended that in each phase of the vaccine rollout, priority should be given to the most socially vulnerable areas. And Wisconsin’s State Disaster Medical Advisory Committee — which lists “mitigating health inequities” as one of its guiding ethical principles — also advised considering socioeconomic status when dividing up the doses.

In any case, making lasting changes to the wide gaps found in this study will require some heavy lifting, Lynch says. There’s no one move that will make these disparities go away; we have to look “upstream” to address the underlying systems, she says.

“We kind of have to have a mind shift where we have to invest in each other, and we have to value everyone equally,” Cousin says. “And yeah, it takes more money up front to fix these problems. But it's worth it.”