This is the last of a four-part series exploring the history and struggles Black Wisconsinites have endured. Read Part 1, Part 2, and Part 3.

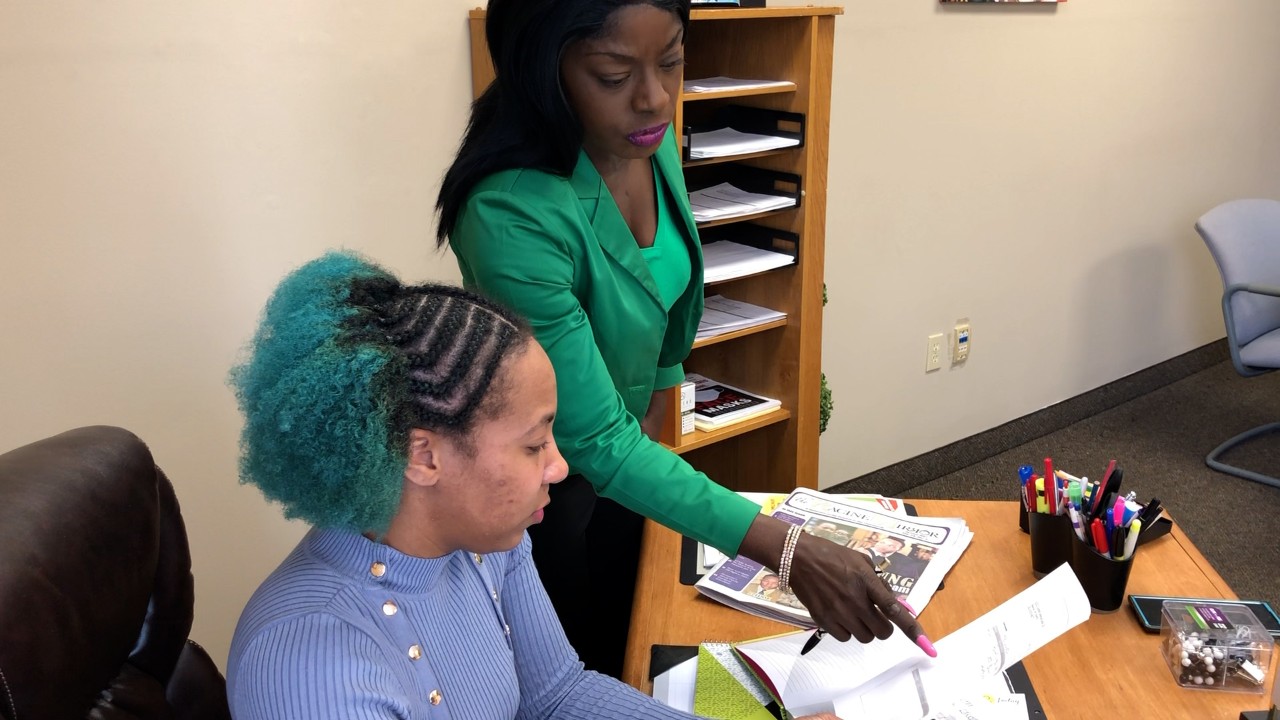

MILWAUKEE — Growing up in Milwaukee, community organizer Angela Lang experienced “a tale of two cities.”

Lang, the executive director of Black Leaders Organizing for Communities (BLOC), loved living in the predominantly Black Merrill Park neighborhood. “It’s where I feel at home,” she said.

But she also saw how other people vilified her community, and felt the deep racial divides that existed between different parts of Milwaukee — which remains one of the most segregated cities in the U.S.

Over the course of this Black History Month, we’ve explored some of the forces that shaped the Badger State since the 1700s. We’ve traced the thread of Wisconsin’s Black history, from the first African slaves brought here by fur traders through the trailblazers of the Civil Rights Movement.

As February comes to a close, we’re turning to look at the 21st century — the realities of our current moment for Black Wisconsinites, including the persistent legacies of segregation and discrimination, and leaders' hopes for shaping the years to come.

For her part, Lang still feels a deep connection to her city, despite its challenges. She’s spent her whole life in Milwaukee, and says there’s something beautiful about working in the community that helped raise her.

“There's a lot of pain and grief and trauma,” Lang said. “There's also a lot of beauty and passion and dedication in our community. And so, I always think about how our community is full of complexities, but at the end of the day, we tend to find joy, and laugh, and try to find ways to support each other.”“There's a lot of pain and grief and trauma,” Lang said. “There's also a lot of beauty and passion and dedication in our community. And so, I always think about how our community is full of complexities, but at the end of the day, we tend to find joy, and laugh, and try to find ways to support each other.”

Deep divides persist

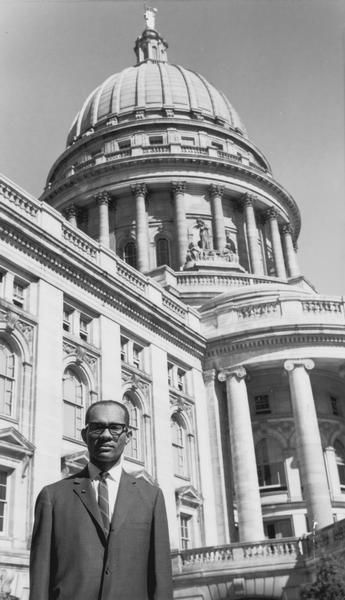

During the Civil Rights Movement, Black Wisconsinites fought fiercely to change laws and practices that kept them separate and unequal.

By the time the 21st century kicked off, school segregation and housing discrimination had both been officially banned. But equality is about much more than the letter of the law, pointed out Rev. Dr. Alex Gee, the founder and president of Madison nonprofit Nehemiah.

“Laws have changed, so we're appreciative of that,” Gee said. “But laws don't change attitudes.”

Long after the federal Fair Housing Act passed in 1964, racial segregation has persisted in Wisconsin. A recent WalletHub data analysis ranked Wisconsin as the most segregated state in America.

In particular, Milwaukee — which was home to 200 consecutive nights of open housing protests in the 60s — continues to see sharp racial divisions between different parts of the city.

As researchers from the UW Applied Population Lab found, current Milwaukee neighborhoods still have a lot in common with the redlined maps that cut up the city into demographic chunks in the 1930s. And as of last year, Milwaukee had the second-lowest rate of Black home ownership of any large metro area in the country.

“It feels that Milwaukee will always be kind of segregated,” Lang said. “A lot of times, we don’t cross those bridges.”

Even though housing segregation is no longer written into laws and policies, it’s still upheld by social and economic inequalities.

The same trends show up in employment, wealth, health care, and education: While the Civil Rights Act tried to level the playing field for African-Americans, huge discrepancies still exist in the Badger State. A 2019 report found that Black Wisconsinites were more likely to be unemployed, less likely to hold a bachelor’s degree, and on average, made less than half of their white counterparts’ income, among other disparities.

Gee said it’s important to recognize the remaining legacies of systems that were built to exclude Black people, and the hurdles that they still have to jump in order to succeed.

“To whatever degree the Black community is struggling,” Gee said, “it's because the nation as a whole is struggling to allow all of its residents to have the same access to resources, and opportunities, and education.”

The COVID-19 pandemic has highlighted these disparities and, in many cases, turned racial inequality into a matter of life and death.

In Wisconsin, Black and indigenous residents have gotten sick and died from COVID-19 at higher rates than white residents, according to DHS data. Even so, as COVID-19 vaccines have rolled out in the state, white Wisconsinites have gotten access to the shots at higher rates than Black residents.

Beyond the disease itself, Black communities have also suffered from the pandemic’s other challenges, Lang pointed out — from domestic violence to mental health challenges to economic anxiety.

“We know that communities of color tend to be the most disproportionately impacted by COVID and all of the side effects that come with it,” Lang said.

Crime and punishment

In recent decades, the criminal justice system has also had a huge, and hugely disproportionate, impact on Black Wisconsinites.

As of the 2010 census, Wisconsin was locking up Black men at the highest rate of any state, as Bloomberg CityLab reports. And Milwaukee’s 53206 zip code — a predominantly Black neighborhood — is known as the most incarcerated zip code in the country.

High incarceration rates and long sentences are, in part, a spillover from the “tough on crime” rhetoric and policies of the late 20th century, said Jerome Dillard, the executive director of Ex-Incarcerated People Organizing (EXPO).

“Truth-in-sentencing” bills cut down on parole processes so that incarcerated people were serving out longer sentences. And the 1994 crime bill sent correctional systems “through the stratosphere,” Dillard said, escalating the war on drugs and providing more funds to police and prisons.

Dillard himself served time in federal prison, and said he saw firsthand the effects of these policies.

“What really touched my heart and saddened me was all the times that I watched busload after busload of young, predominantly Black men coming into that prison,” Dillard said. “Coming into those prisons with 25, 30, 40 years for drugs.”

As the Black Lives Matter movement swept the U.S. in recent years, Wisconsin has also faced its own reckonings with police brutality.

The police shooting of Jacob Blake in August sparked huge protests in Kenosha and garnered national attention. Before Blake, other Black Wisconsinites had become tragic rallying cries for police reform — from Alvin Cole to Isaiah Tucker to Dontre Hamilton.

For Dillard and Lang, the way forward for Wisconsin’s justice system should involve reinvestment in Black communities.

Lang believes providing for people’s basic needs is a more effective way to prevent crime, instead of increasing police presence or opening more prisons.

“Something that we've been working on pretty much since day one is having the conversations around divesting from the justice system and investing directly into our community,” Lang said.

Dillard said he’s been proud to see many of the people he met in the prison system return to their communities. But he stressed that the reentry process requires support too — and organizations like EXPO are still fighting for fair housing, living wages, and voting rights for formerly incarcerated Wisconsinites.

“We're in a time and an era where those wrongs need to be righted,” Dillard said. “There needs to be an investment in the communities and these individuals who make up the vast population of our prison system.”“We're in a time and an era where those wrongs need to be righted,” Dillard said. “There needs to be an investment in the communities and these individuals who make up the vast population of our prison system.”

Building power, and finding joy

Though many challenges remain, these Black leaders say they’re hopeful about the chance to create a more equitable future.

“Where we are right now is understanding that we really can't continue to ask for permission to speak, to think, to organize, to create wealth,” Gee said. “Because we've been at this for 400 years on this soil, and what we're understanding is equality has never just been handed to us as a right.”

Lang says in recent years, she’s seen more and more people get involved with organizing in the community. And she’s been inspired by growing representation among the state’s elected officials, like Lt. Gov. Mandela Barnes and Milwaukee County Executive David Crowley, who are the first Black people to serve in their respective roles.

Working with BLOC, Lang hopes to keep growing that civic engagement in her community. Right now, the group is working to advocate for justice reform and pandemic relief, as well as generally giving everyone the tools to make their voices heard.

“It's unfortunate that we have to organize around so many different issues,” she said. “But I'm glad that we're slowly building that infrastructure and that power here in Milwaukee to tackle those things.”

When it comes to the future of Wisconsin’s criminal justice system, Dillard said he’s feeling “optimistic” for the first time in many years.

He said he’s been excited to see a push for reform start to come to life, and wants organizations like EXPO, whose members have firsthand experience with incarceration, to be at the table.

“One of my visions is that those who are impacted by this — those who are closest to the problem — are able to be part of the solution,” Dillard said.“One of my visions is that those who are impacted by this — those who are closest to the problem — are able to be part of the solution,” Dillard said.

Gee also stressed that creating a brighter future will mean working in solidarity with other communities. His organization, Nehemiah, works to help give Black residents the tools to thrive, while also training allies to speak out against racism.

Nehemiah is working to raise funds for a physical Center for Black Excellence and Culture — a place for people to connect, learn, and thrive.

For Gee, moving forward means recognizing the struggles that still exist for African-Americans today, while also celebrating the rich cultural legacy they share.

“My dream is that my race does not hinder people's perception of me, nor does it hinder access for me,” Gee said. “But at the same time, I do not want my cultural heritage ignored, because it is beautiful. It's fantastic. And for 400 years, it has not been able to be beaten out of us.”