This is part three of a four-part series exploring the history and struggles Black Wisconsinites have endured. Read Part 1 and Part 2 here.

MILWAUKEE — Like in the rest of the U.S., the 20th century in Wisconsin was a time of major change — and major growing pains.

More Black residents than ever before would move into the Badger State during this era. But when they arrived, they’d find a place that still systematically denied them equal rights and opportunities.

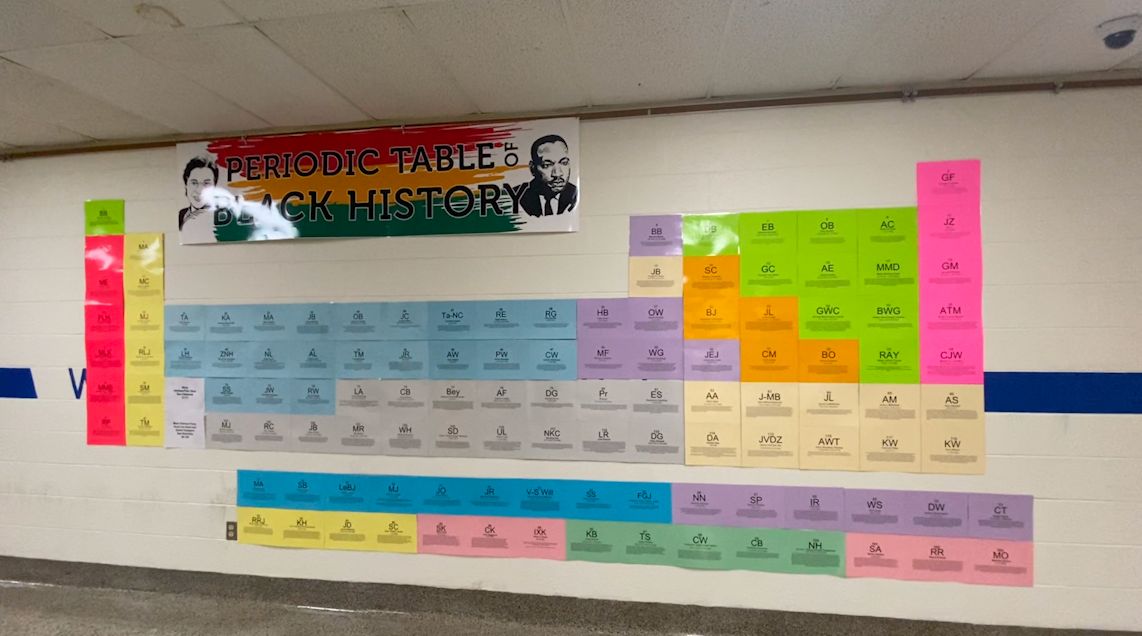

Over the course of the century, Black Wisconsinites would have to fight tooth and nail to earn the same rights that their neighbors were given freely. Here, we take a look at the persistent issues of segregation and prejudice that faced Black residents at this time — and the Civil Rights Movement that helped bring about hard-earned progress.

Change, and backlash

The early 20th century saw limited opportunities for Black Wisconsinites, even as a tide of migration brought more African-Americans into cities like Milwaukee.

Employment was hard to come by: Factories were segregated, farms weren’t hiring, and a lot of skilled jobs had already gone to earlier immigrants to the state, according to the Wisconsin Historical Society.

And while Black residents had won some important victories by this point, including securing the right to vote, prejudice and discrimination were still widespread. The Union’s victory in the Civil War and new rights for African-Americans across the country prompted backlash from some white Americans, said UW-Madison historian Christy Clark-Pujara.

“There are threats on their land, threats on their lives,” Clark-Pujara said. “By the time we get to the 20th century, we have well-known, well-established sundown towns throughout rural Wisconsin.”

The Ku Klux Klan emerged in Wisconsin starting in the 1920s, as WPR reports, targeting Black residents as well as Catholics, Jews, and other immigrants. A 1924 article in the Wisconsin State Journal describes a parade of around 1,300 Klansmen in Madison, where burning crosses and fireworks drew large crowds.

Of course, the beginning of this century was also defined by two world wars and an economic crash in the U.S. The Great Depression hit Black Wisconsinites hard: Nearly half of Black residents were unemployed as of March 1940, according to the Wisconsin Historical Society.

It was after World War II that the trickle of Black migration became a wave. Thousands of Black residents moved to Wisconsin from southern states, seeking out a growing range of industrial jobs in cities like Milwaukee, Madison, and Racine.

As of 1910, there were fewer than 3,000 African-American residents in the state; by 1960, there were nearly 75,000.

Much of this migration was driven by economics, said Erica Metcalfe, an assistant professor of history at Georgia Gwinnett College. But other factors also played a big role, said Metcalfe, a Milwaukee native who has studied the city’s civil rights movement.

“They’re trying to get away from a lot of things,” she said. “They’re leaving the South. They’re trying to escape poverty and sharecropping. They’re trying to escape racial violence and lynching. They’re trying to escape disenfranchisement, not being able to vote.”

Separate and unequal

For incoming Black Wisconsinites, though, the place that was supposed to be their escape was itself far from perfect, Metcalfe said.

Housing segregation still ran rampant in cities like Milwaukee, even though it wasn’t codified in Jim Crow laws. This “de facto segregation” was built on things like racially restrictive covenants — in which homeowners explicitly agreed to never sell their real estate to Black people — and redlining, as well as plain old economic competition.

By the mid-20th century, Milwaukee was one of the most racially segregated cities in the U.S., with Black residents basically isolated on the Near North Side, Metcalfe said.

Schools were also highly segregated at the time, even after the Supreme Court ruled in Brown v. Board of Education that “separate but equal” wasn’t good enough.

Districts had neighborhood school policies so that kids would attend schools close to home, Metcalfe explains. But since neighborhoods were so segregated, their schools were too — and, as civil rights leaders would argue, the Milwaukee School Board drew boundaries to enforce those separations, instead of pushing toward integration.

In 1960, a survey by the NAACP found that 90% of students in central Milwaukee schools were Black, according to the Wisconsin Historical Society.

Plus, a practice known as “intact bussing” kept Black and white students apart even on the same campuses.

Per the school board’s instructions, classes from overcrowded schools — usually made up of Black students — would ride over to schools with more space. But they wouldn’t mix with the students in receiving schools; instead, they’d stick with their own segregated groups, and sometimes would even have to ride back to their regular schools to eat lunch.

In this way, Black Wisconsinites who had moved from the South were seeing many of the same injustices repeated in their new home, Metcalfe said.

“To come north, and to see the same issues coming back, where can you go?” Metcalfe said. “There’s no place that you can really go to escape. Instead of trying to continue to migrate, you have to fight back.”

Marching on Milwaukee

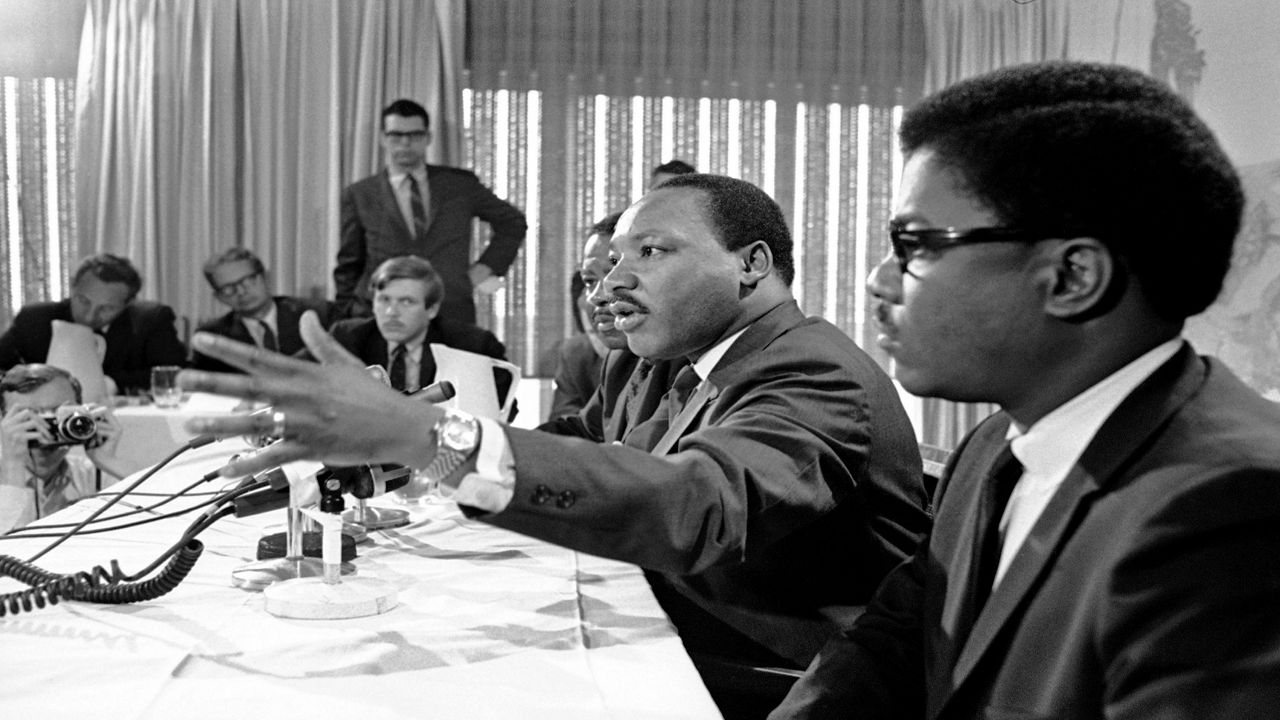

So, as the Civil Rights Movement swept the nation in the late 20th century, Wisconsin was no exception.

Milwaukee especially saw fierce fights for desegregation and equal rights. Metcalfe said one of the major sparks for the movement was the 1958 death of 22-year-old Daniel Bell, who was killed by Milwaukee police after a routine traffic stop.

After that point, she said, more and more groups started picking up the fight.

“It was just a matter of equality,” Metcalfe said. “That was what everyone was fighting for in the Civil Rights Movement — to have the same rights as everyone else, to not discriminate according to race.”

A lot of early efforts in Milwaukee centered on the issue of school segregation. Groups like the NAACP, the Congress of Racial Equality (CORE), and the Milwaukee United School Integration Committee (MUSIC) demanded that the school board work to truly desegregate classrooms.

Activists led demonstrations and a series of school boycotts. They set up “Freedom Schools” to offer kids a special curriculum during the boycotts, which drew huge numbers of Black students from across the city.

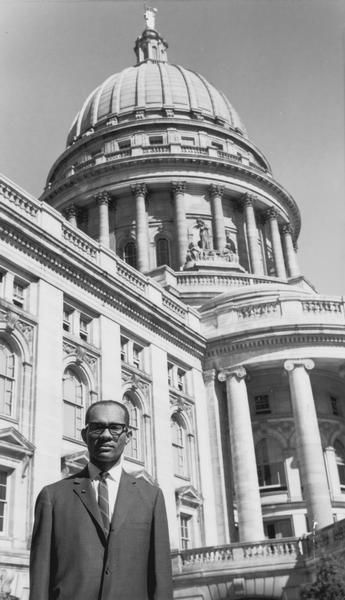

And, eventually, they took their efforts to the courts: Lloyd Barbee, an attorney and prominent civil rights leader, filed a federal lawsuit against the school board in 1965.

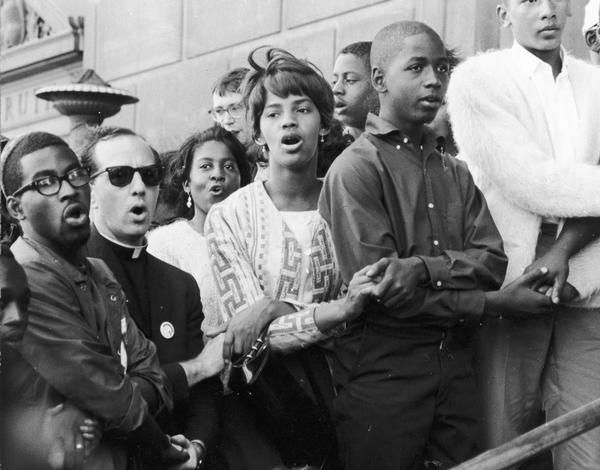

While Barbee’s case worked its way through the justice system, direct actions continued on the open housing front, Metcalfe said. One of the main groups leading the charge was the NAACP Youth Council, an organization of mainly teenagers and young people that was dedicated to nonviolent protest.

The Youth Council was a bit different from other groups across the Civil Rights Movement, Metcalfe said. Though there were mostly Black members, the group was integrated and welcomed white members, too. And, under the leadership of priest and activist Father James Groppi, it was one of the rare groups to be centered on the Catholic faith.

“They were determined to maintain their movement how they wanted it,” Metcalfe said. “To maintain an integrated movement, a nonviolent movement.”

The Youth Council held its first direct action campaign in 1963, protesting Marc’s Big Boy Restaurant for hiring discrimination. In 1966, they set their sights on the whites-only Eagles Club, picketing outside the houses of judges who were club members.

And in 1967, the group kicked off a massive open-housing campaign with a dramatic protest: Hundreds marched from the Near North Side to the city’s heavily white South Side, crossing over the so-called “Mason-Dixon Line'' of Milwaukee. Thousands of white counterprotesters gathered to face off with the marchers and throw bottles at the crowd.

“It was definitely a scary situation. There were a lot of a lot of injuries when they returned from the south side,” Metcalfe said.

But despite the backlash, the Youth Council continued to march for 200 more consecutive days.

And, as their direct actions gained national attention, the groundbreaking Vel Phillips was also fighting for fair housing in the City Council. Phillips repeatedly brought up open-housing legislation in the council for years after first introducing it in 1962.

Finally, the tides started to turn: In 1968, the U.S. government passed a federal open-housing law in the wake of Dr. Martin Luther King Jr.’s assassination. A few years later, in 1976, a federal judge ruled that Milwaukee’s schools were illegally segregated, handing Barbee a win in his long-running case.

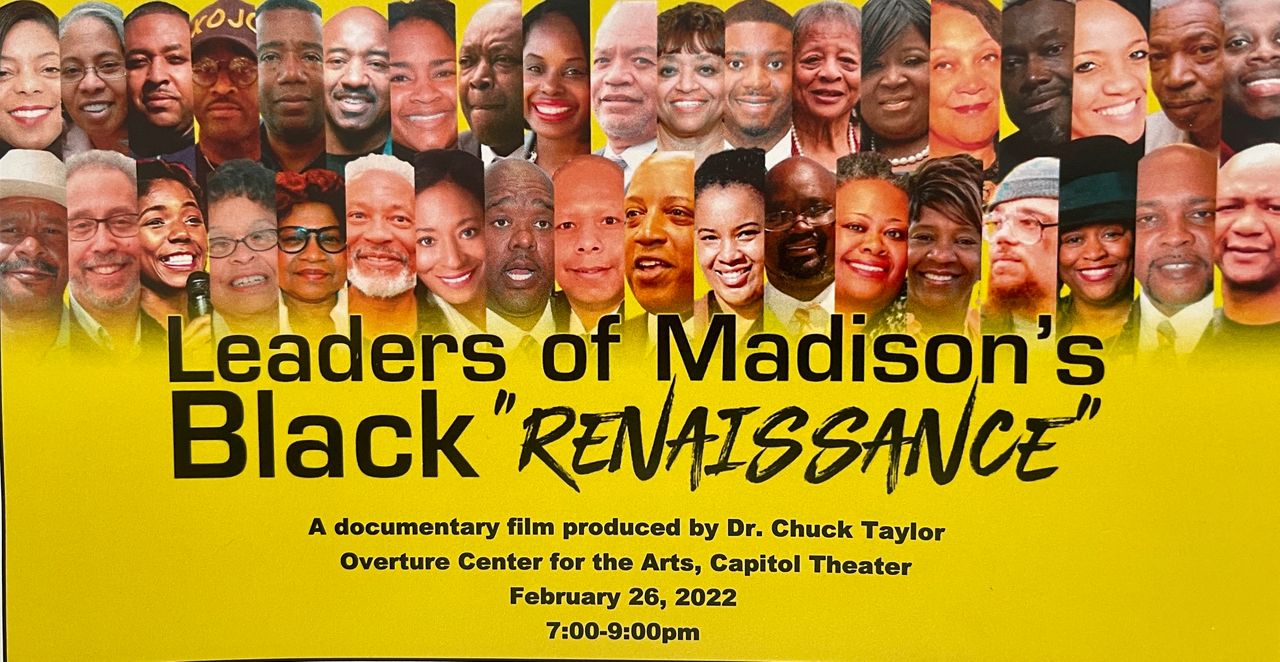

These moves didn’t immediately solve segregation, of course, Metcalfe said. But eventually, they would lead to some important changes, with a stronger Black middle class emerging and getting access to new opportunities.

As the 20th century came to a close, then, there was certainly some hard-won change for the better. And yet, new issues were emerging too, Metcalfe points out, from economic downturn to rising incarceration and the influx of the drug trade.

“There are some things that have improved, definitely, but there's still a lot of issues that need to be addressed,” Metcalfe said.

To this day, we’re still facing some of the same problems that activists like Barbee, Phillips, and Groppi were fighting. Metcalfe said that’s one reason to pay attention to the history of their efforts, and understand what lessons they hold for our future.

“If we look at history, and look back at where we’ve been — what worked, what didn’t work — it would make it a lot easier to move forward,” Metcalfe said. “You know, people always say: ‘You don’t know where you’re going until you know where you’ve been.’”