This is part two of a four-part series exploring the history and struggles Black Wisconsinites have endured. Read Part 1 here.

MILWAUKEE — As the 19th century rolled around, Wisconsin was just figuring out its future.

Well, technically, Wisconsin wasn’t Wisconsin yet — it was a chunk of land handed over to the brand-new United States. American settlers, including Black residents, were starting to flow into the future Badger state, seeking out land or opportunity.

These new residents would grapple with questions of freedom and abolition, civil rights and political power. Here, we take a look at how Black Wisconsinites navigated the 19th century in their young state — and the lasting, sometimes contradictory, effects of the era.

Slavery is banned, eventually

In 1787, the Northwest Ordinance, which set the standards for how Wisconsin and the surrounding Midwest would be brought into the new United States, banned slavery from the region.

But the rules didn’t translate into reality, says Christy Clark-Pujara, a UW-Madison associate professor who studies the history of African Americans in the Midwest.

“As historians have uncovered and continue to uncover, it wasn't worth the paper it was written on,” Clark-Pujara says. “In practice, slavery was happening throughout the Northwest Territory.”

In the 1820s and ‘30s, lead mining was a huge business in the land that would become the Badger State. Many of the white settlers, who flocked in to take advantage of the lead boom, came from slaveholding states, and brought enslaved African Americans with them.

Without any real enforcement of the ban, these settlers were still able to force slaves into the “excruciating, backbreaking labor” of digging up lead, Clark-Pujara says.

Henry Dodge, the first territorial governor of Wisconsin, was known to have five enslaved men — Toby, Tom, Lear, Jim, and Joe — working as smelters for him long after he promised to free them, as UW-Madison’s “Wisconsin 101” project explains. Military men at Fort Crawford also kept enslaved Black people to work as their servants and maintain the base, Clark-Pujara says.

“The fact that they were able to keep people in bondage illegally, with the consent of their neighbors, is very telling,” Clark-Pujara says. “It tells us how enshrined race-based slavery was in the nation, that it was practiced in territories where it was explicitly, legally banned.”

Slavery finally started to fall apart in the region when Wisconsin got its statehood. Wisconsin entered the union as a free state in 1848; by that time, former slaveowners had emancipated their slaves — people who should have never been held in bondage in the first place, Clark-Pujara points out.

So, while slavery was technically banned in Wisconsin early on, it took 60 more years for the institution to actually break down.

The number of enslaved people here was smaller than in the south, Clark-Pujara says. And there were free Black residents who thrived in Wisconsin at the time too, with some forming rural settlements in the Cheyenne Valley and Pleasant Ridge.

But the idea of slavery as something that only happened on cotton plantations is a myth, she says — and hundreds of Black Wisconsinites were still subject to the “violence, and force, and coercion, and degradation” of slavery.

Fighting for freedom

Even as some Wisconsinites were just freeing the slaves they’d kept illegally, others were speaking out strongly for abolition.

Accounts from the pastor John Nelson Davidson, published online by the Wisconsin Historical Society, describe how some churches spoke out strongly against slavery at the time — with one group of clergy declaring “American slavery is a sin,” and “a sin of such magnitude that all who practice it, or knowingly promote it, should be excluded from our pulpits and the fellowship of our churches.”

And, as Davidson writes, “deeds followed words”: Wisconsin’s abolitionists helped some slaves escape into Canada along the Underground Railroad.

In the first recorded escape, an enslaved teenager named Caroline ran away from St. Louis in 1842 and relied on the help of allies in Milwaukee and Waukesha to get out of her enslaver’s reach.

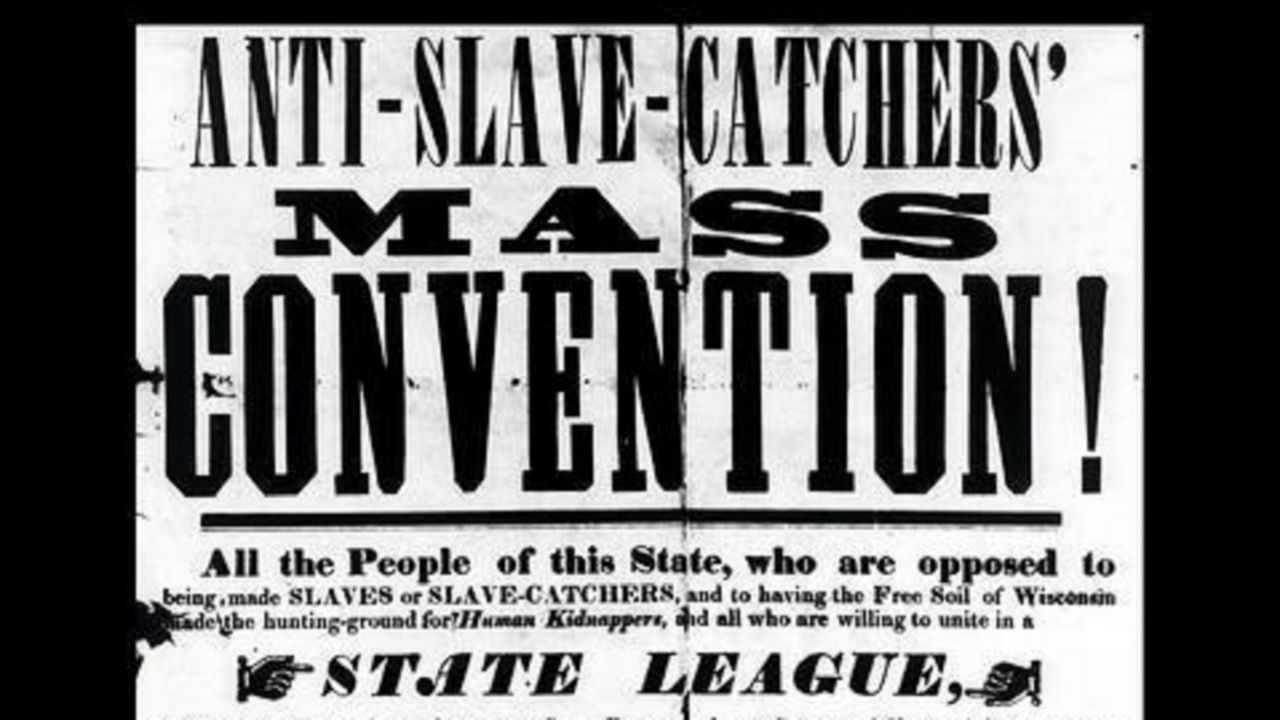

And in probably the most well-known story, a crowd of abolitionists — both Black and white — broke down the doors of the Milwaukee jail to free Joshua Glover, a fugitive slave who was being held there.

When the leader of the mob was later arrested himself for the breakout, he argued that the Fugitive Slave Law, which allowed for escaped slaves to be captured and returned, was unconstitutional. The Wisconsin Supreme Court agreed, taking the stance that “they won't be the slave catchers of the federal government,” Clark-Pujara says.

In 1861, of course, such conflicts — of states’ rights and of slavery — came to a head as the Civil War broke out, with Wisconsin on the side of the Union.

At first, Clark-Pujara says, the war was seen mainly as a fight to keep the country together. It’s only after Lincoln makes the Emancipation Proclamation in 1863 that “the Union Army becomes an army of liberation, and emancipation becomes part of that project,” she says.

After that point, hundreds of Black soldiers from across Wisconsin joined up to fight in the war — after originally being barred from enlisting in the Union Army.

“Oppressive and progressive”

Black Wisconsinites were fighting another important battle in the 19th century: They wanted the right to vote.

The original 1848 constitution that made Wisconsin into a state only granted suffrage to white men, which Clark-Pujara describes as “specific and clear exclusion of Black people from political power.”

In 1849, when the issue of Black suffrage was put up to a vote in a statewide referendum, the majority of (white, male) voters didn’t answer the question.

Election officials chose to count every abstention as a vote against Black suffrage, and so the measure failed. Years later, in a follow-up referendum, most white men decided against allowing Black Wisconsinites to vote.

But “free Black people weren’t about to accept that,” Clark-Pujara says. Black Wisconsinites and their allies started pushing back and organizing.

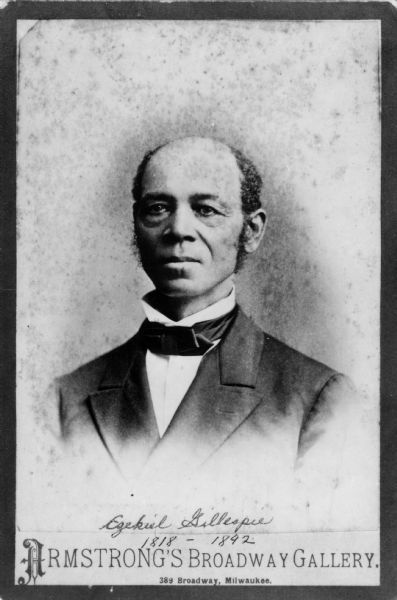

Finally, in 1866, Ezekiel Gillespie, a Black leader in Milwaukee, sued the state for his right to vote after being turned away from the ballot box — with abolitionist lawyer Sherman Booth strategically in tow.

Gillespie won his case, with the state Supreme Court ruling that the original referendum should have passed instead of counting abstentions as “no” votes. From that point on, Wisconsin became the first state in the Midwest to give Black men the right to vote.

But the struggle over suffrage shows that even after the war, and even with the stories of fervent abolitionists helping slaves to freedom, Wisconsin’s treatment of Black residents in this era was complicated at best, Clark-Pujara says. As she describes it, the Badger State managed to be both “oppressive and progressive” at the same time.

“A Black person that’s escaping slavery and running through Wisconsin, they can expect to find help,” Clark-Pujara says. “But then a Black person who wants to settle and live their life there, they find themselves on the margins.”

So, as the 19th century came to a close, Wisconsin’s Black residents were faced with a duality that was being repeated all across the country.

This period saw the end of the Civil War, the passage of the 13th Amendment, and, in Wisconsin, the establishment of Black suffrage. But, as the Wisconsin Historical Society describes, there were also lynchings, segregation, and efforts to stop Black people from moving into the state.

Even with some struggles won, others were just beginning.

“Black people in America after the Civil War find themselves in limbo,” Clark-Pujara says. “Not in slavery this time, but not as protected citizens. And so, while the right to vote was relatively sure for Black men [in Wisconsin], Black people's acceptance into society, whether it be social, political or economic, didn’t happen.”