This is part one of a four-part series exploring the history and struggles Black Wisconsinites have endured.

MILWAUKEE — The record of Black history in Wisconsin starts with a tragedy.

In 1725, a chief of the Illinois Indians gives a speech. He reports that a warring tribe has killed a group of people up in Green Bay: Four Frenchmen and a Black slave “belonging to Monsieur de Boisbriant.”

It’s the earliest-ever mention of Black residents in the land that would become the Badger State, according to the Wisconsin Historical Society.

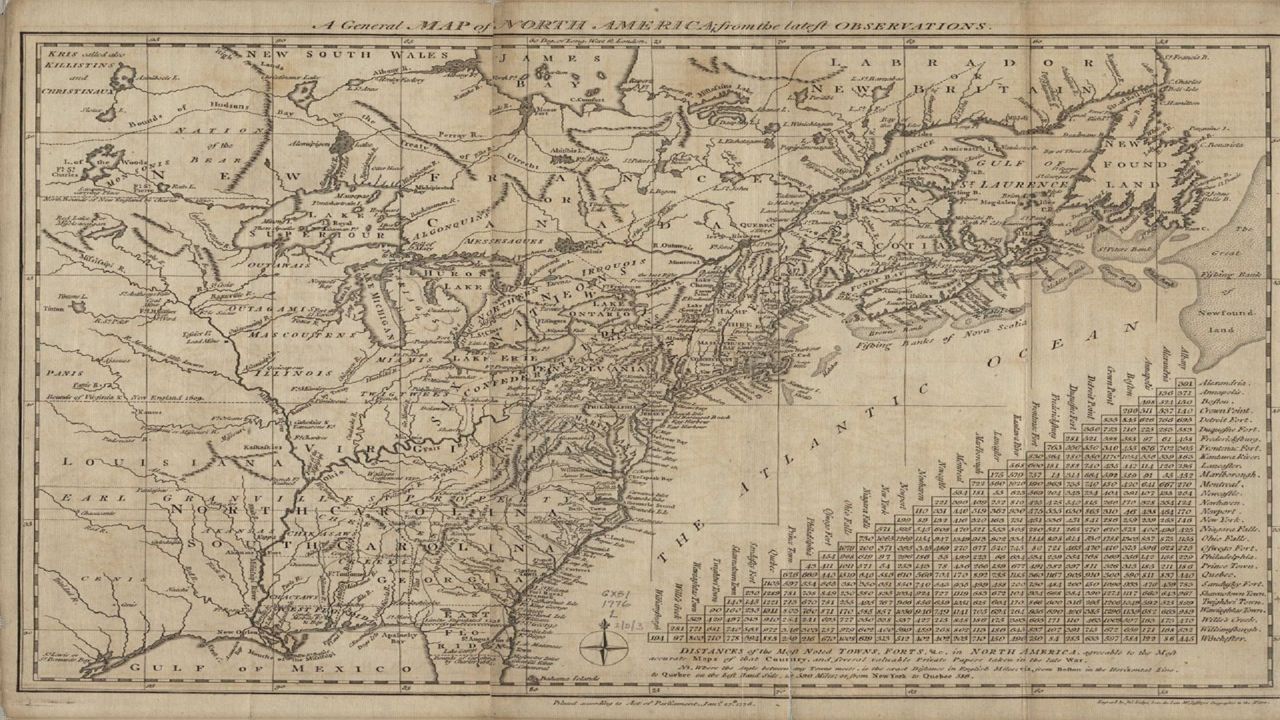

Records like this show that, as is the case across the country, the first Black people didn’t come to Wisconsin by choice. Most were slaves brought by Europeans, including the French fur traders who ranged across the Great Lakes before the U.S. was born.

The story of Black Wisconsinites has come a long way since then.

Over the course of this Black History Month, we’ll be unpacking that story in a four-part series — one for each century that Black residents have been part of the state’s historical record. We’ll track some of the major trends, events, and figures, from the battles over suffrage and segregation all the way through our current moment.

For those early days in the 18th century though, records of Black Wisconsinites are somewhat sparse.

In his recollections from the early days of Wisconsin — published online by the Wisconsin Historical Society — the French fur trader Augustin Grignon makes several mentions of Black residents in the area.

There were some free Black traders who made waves in the Midwest at the time: Grignon recounts that two Black traders set up shop in Marinette in the late 18th century. And the Black pioneer Jean Baptiste DuSable would become known as the “Father of Chicago” after building a successful trading post on the shores of Lake Michigan.

But most of the recorded Black Wisconsinites at the time were slaves in the service of European merchants and military men.

Grignon’s records talk of one French captain who was known to have a Black servant, “who I presume was a slave,” he writes. Grignon adds that another trader at Green Bay bought a young Black boy — “a mere lad, not over half a dozen years of age” — as a slave, and proceeded to be “inexcusably severe in punishing him.”

In 1760, the French, who originally claimed the land, were preparing to surrender the region to Great Britain after years of conflict. According to Grignon’s account, the terms of surrender allowed the French to keep their Black and Pawnee slaves — although any slaves taken from the British would have to be given up.

Of course, the British wouldn’t keep their claim for too long: Once the American Revolution ended in 1783, they’d turn Wisconsin and the rest of the Great Lakes over to the newly-minted United States.

And in 1787, an important document would leave a lasting mark on Wisconsin’s history. The Northwest Ordinance, which set the ground rules for bringing the Midwest into the new union, established the rights of the new Americans in the region, including freedom from slavery.

“There shall be neither slavery nor involuntary servitude in the said territory,” the document proclaims. (Though there were some exceptions: Escaped slaves from other states “may be lawfully reclaimed,” and servitude was still OK as a punishment for convicts, according to the ordinance.)

With this promise, Wisconsin and its neighboring states declared a ban on slavery early on, nearly a century before the 13th Amendment did the same for the rest of the country.

Still, for Black Wisconsinites, the fight for true freedom was far from over. In fact, their story was just getting started.