CINCINNATI — Leaders in the greater Cincinnati region hope a cutting-edge approach to reducing carbon emissions will help them make major progress in efforts to battle climate change as early as next year.

What You Need To Know

- Cincinnati Parks and Great Parks of Hamilton County have unveiled a plan to begin jointly producing biochar, or biological charcoal

- The $1.1 million project aims to remove carbon from the atmosphere and improve regional resilience to climate change

- Plans call for use of the biochar on public property, but also for the sale of it to local farmers and organizations

- The goal is for the project to start no later than March 2024

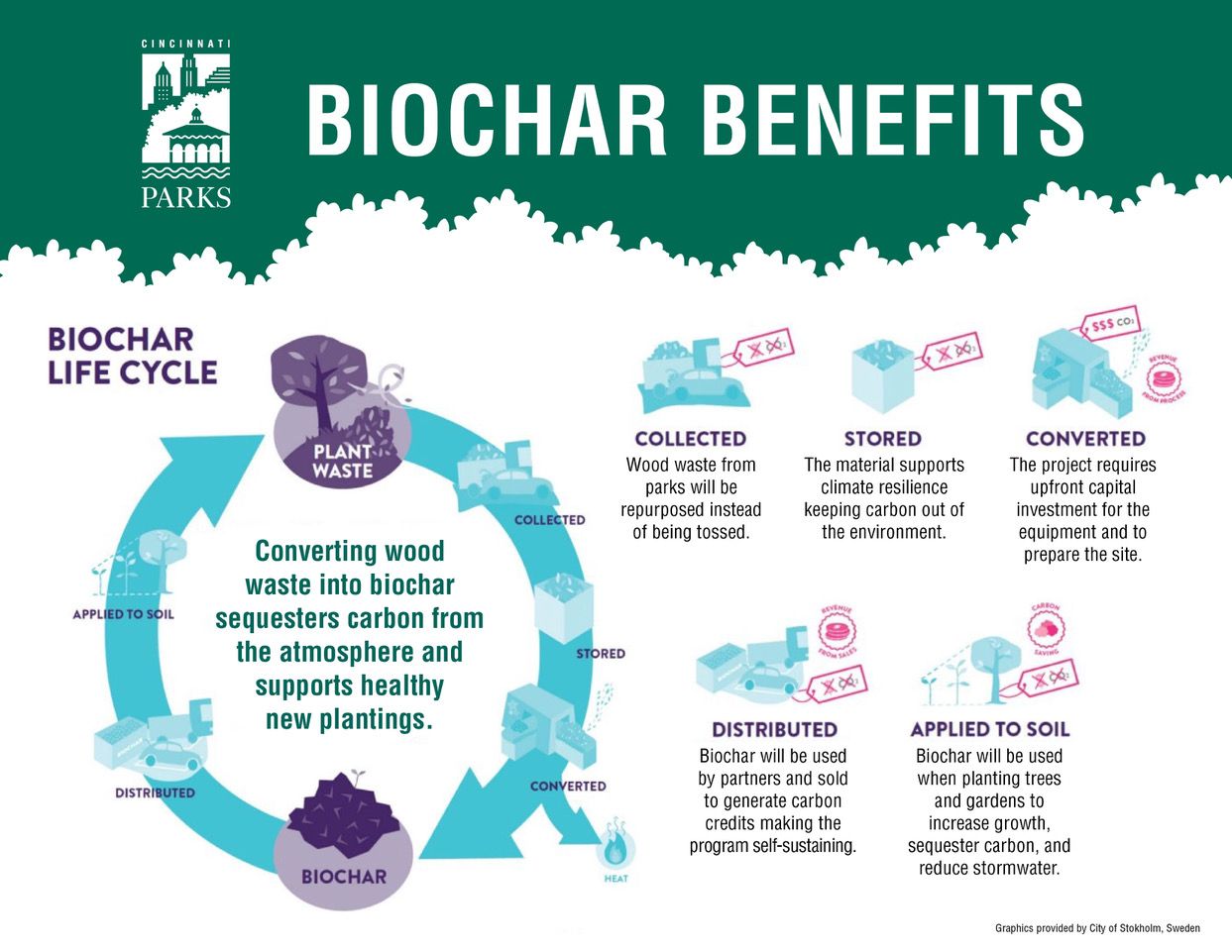

The boards for Cincinnati Parks and Great Parks of Hamilton County have unveiled a plan to begin jointly producing biochar, or biological charcoal, which is a byproduct of an environmental process that helps remove carbon from the atmosphere.

Including grants, the initial project commitment is $1.1 million.

Once the operation is up and running, the park systems plan to repurpose wood debris from tree maintenance operations into a special carbon-capturing, carbon-negative product similar to charcoal. They’ll do so by cooking it without oxygen, a process called pyrolysis.

The team wants to use the biochar as a soil additive to support the health of new tree plantings while also storing carbon to enhance climate resiliency.

Greater Cincinnati is one of the first areas in the United States to adopt this approach on a large scale, according to Cincinnati Parks. The model is a municipal project started in Stockholm, Sweden, a few years ago.

“Why would we continue dumping tons of wood waste into the forest to decompose when we have a chance to capture all that carbon and create a new super material allowing trees and plants to grow faster?” asked Jason Barron, director of Cincinnati Parks. “On both ends, we’re making a difference.”

Barron praised Great Parks and other project partners who “stepped up big” in this effort to lead climate resiliency efforts in Cincinnati.

The Cincinnati Board of Park Commissioners and Great Parks each recently committed $300,000 to support the program. This is besides a $400,000 grant received this summer from Bloomberg Philanthropies and $100,000 previously committed by Cincinnati’s park board.

“This partnership creates an opportunity for our community to lead the way in conservation, not only by reducing our carbon footprint but also by providing a more sustainable solution to upcycle the substantial amount of natural waste generated within our parks and conservation areas,” said Great Parks CEO Todd Palmeter.

The biochar team is using the funds to get the project off the ground, said Rocky Merz, Cincinnati Parks’ spokesperson. He said the long-term plan is to offset the annual operating expenses, such as maintaining the facility and replacing specialized equipment, through the carbon credit sales and by selling some of its biochar supply on the private market.

“The first step will be to begin production for internal use, then (add) the sales piece,” Merz added. “A detailed timeline is being developed, but the goal is to make the program self-sustaining.”

Cincinnati Parks recently selected a consultant, Carbon Harvest LLC, to help plan the new biochar production facility in Cincinnati’s Mount Airy neighborhood, operate the biochar production and co-manage the project.

They’re locating the equipment at an existing facility on Diehl Road, Merz said. Currently, the site mainly houses maintenance workers and their tools, he added, but plans are for “long-overdue site improvements” as part of the construction of a new home for Cincinnati Parks’ Division of Natural Resources.

As part of Carbon Harvest’s contract, it will provide technical expertise and select a technology to actually create the biochar. Company founder Sam Dunlap said the project should be up and running no later than March 2024, but he’s hopeful it will be ready sometime within the next year.

For Phase 2, Carbon Harvest will operate the project, which will involve running the equipment, producing the biochar and facilitating the distribution and sale of the material.

The partnership with Great Parks of Hamilton County will add critical composting components to make the biochar shovel-ready for soil and sales to the public, per Cincinnati Parks.

They want to focus the sales of biochar to local farmers and organizations, Dunlap added, to reduce the environmental effects of shipping it elsewhere.

Once operational, it’s believed the program can repurpose thousands of tons of wood waste into biochar annually, keeping tons of carbon dioxide out of the local environment, according to Cincinnati Parks.

The aim is to align the program’s carbon removal targets with benchmarks laid out in the ongoing Green Cincinnati Plan update, Dunlap said.

Other partners include Bloomberg Philanthropies, the city of Cincinnati’s Office of Environmental Sustainability and the University of Cincinnati.

Ryan Mooney-Bullock, executive director of Green Umbrella, a Green Cincinnati Plan partner, said the concept of biochar has been around for “a really long time.” There’s evidence early farming civilizations used a similar approach, she said.

But seeing it implemented at a regional level is the type of out-of-the-box thinking needed to reduce carbon emissions in an impactful way, she believes.

“Biochar not only sequesters carbon and absorbs stormwater, but it solves waste issues by finding something useful to do with material that might otherwise end up in a landfill,” Mooney-Bullock added. “This is a great example of an innovative public-private partnership working together to combat climate change.”

Increasing growth while improving air in Cincinnati

While plants and trees produce oxygen, they also collect and store carbon throughout their lives. When they die, that carbon is released back into the atmosphere as it decomposes.

Carbon is a greenhouse gas, a main perpetrator in global warming and therefore climate change, Mooney-Bullock said.

Through the biochar process, instead of having all that carbon released into the air, it gets captured and transformed into a stable form of carbon resembling charcoal that has ecological benefits.

Cincinnati’s biochar material will be used in new tree plantings to increase survivability and canopy growth within communities, especially those most at risk from climate change, Merz said.

In the soil, biochar improves drought tolerance, promotes soil health, immobilizes contaminants, and reduces methane and CO2 emissions, Dunlap said. He stressed it can also help limit runoff, which has benefits for urban stormwater mitigation.

Once altered, biochar is composed of up to 75% carbon that resists decomposition, Dunlap said. He noted that biochar then safely stores the carbon for an average of 500 years, effectively removing it from the atmosphere.

Although technical aspects are still being developed, the groups will probably combine biochar and composting, Dunlap said. Great Parks’ Winton Woods features Parky’s Farm, which has several gardens, orchards and animals on its more than 100 acres of land. It produces about 900 tons of manure and bedding each year.

To be used in plantings, the raw biochar is mixed with compost to “charge” the carbon structure with nutrients, Dunlap said.

“Combining biochar and compost together is a common practice. Biochar can offer improvements to both the compost process and product,” he added. “The idea is that city’s parks will produce biochar and Parky’s Farm and Great Parks will produce compost, and they’ll merge the two to be a revenue-generating opportunity for both entities.”

The Cincinnati project is based on the success of a biochar program in Stockholm. It came about after the Scandinavian city won $1 million Bloomberg Philanthropies 2014 European Mayors Challenge to develop its biochar program.

Since opening its first of five planned biochar facilities in 2017, Stockholm has produced more than 100 tons of biochar and distributed it to 300,000 residents, per data from Cincinnati Parks. Dunlap said that’s the equivalent of removing the equivalent of 700 cars from city streets.

In addition to start-up funding from Bloomberg Philanthropies, the organization is providing the Cincinnati team with lessons learned from Stockholm’s experience.

“We hope to exceed the Stockholm numbers, and anticipate that impact will increase over time,” Merz said.