COLUMBUS — K-12 schools are scaling back in-person instruction due to the worsening coronavirus crisis, announcing learning model changes against the backdrop of loudening calls from the political arena for schools to let students back into the classroom.

In the last couple weeks as the coronavirus crisis has spiraled, superintendents have announced controversial switches from in-person to hybrid learning, from hybrid to virtual, or postponing plans to shift to more in-person instruction.

Infections reported to schools are by and large occurring outside of the classroom, officials say. In Ohio, Dublin City Schools, which has reported 81 total cases out of its 23 schools, contact tracing has only linked one case to transmission inside the school, Superintendent Todd Hoadley said. In that case, a teacher is believed to have spread the virus to a student.

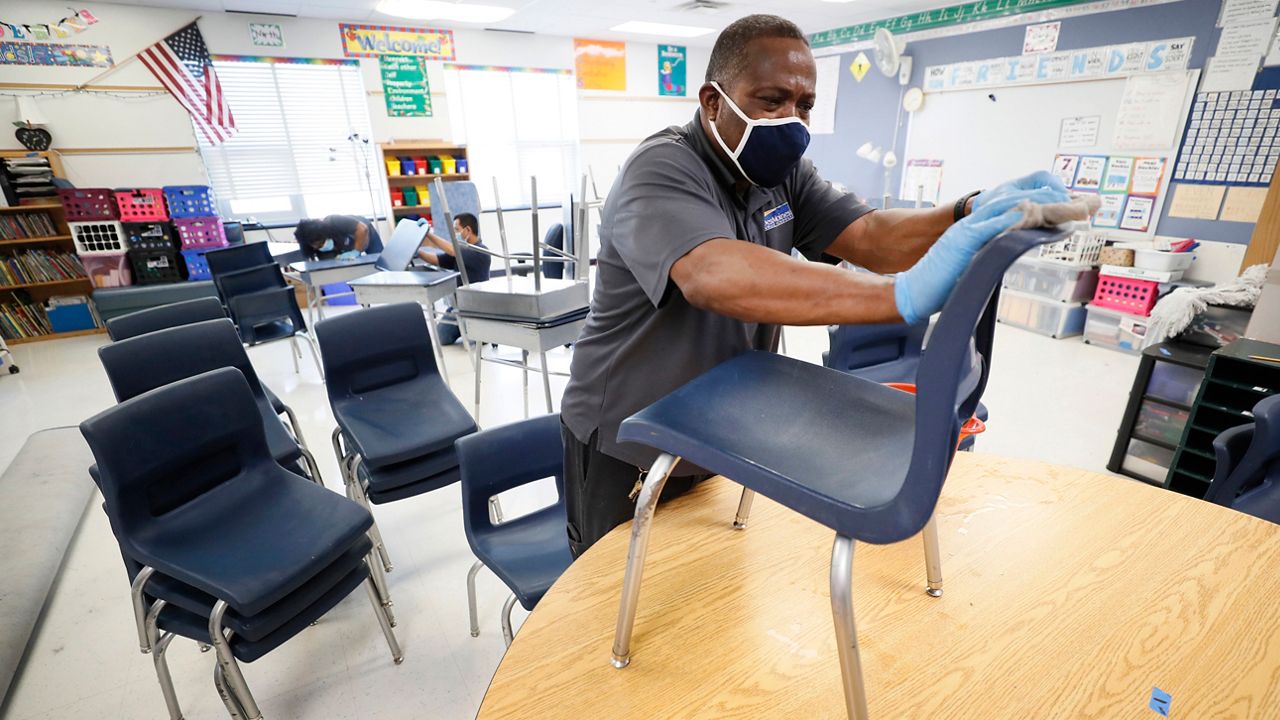

Hoadley said the district’s hybrid-learning model is keeping students safe at their schools. Nearly everyone is wearing masks, with a few exceptions for children with disabilities. The reduced class sizes allow for desks to be distanced.

So how is the virus spreading in school communities? School and public health officials say students are congregating without masks for birthday parties, sleepovers, and after-school hangouts, creating environments for transmission beyond schools' control.

In one instance, a Dublin family hosted a “pseudo middle school dance,” Hoadley said. They decorated their basement and hosted about 30 kids for a celebration and a sleepover with the girls. Another family hosted a homecoming gathering.

“We cancel homecoming, so 20 kids get together at somebody's house and have a homecoming dinner with no masks, no social distancing,” Hoadley said. “We had a student that should have been in quarantine go to this homecoming event. Four or five days later, like five of the students are COVID positive and the rest of the students, 15, are on a two-week quarantine.”

Concerned members of the school community send social media posts of the gatherings to the district. Hoadley says he calls the families and pleas for them to take the students’ safety seriously.

“I've got four children myself, and I understand the feeling like these are missed experiences for students. And as parents, they want to try to work to fill in the gap of something that was missed,” he said. “So we contact the parents and say, ‘Look, we need your help. We need you not to do this. We all have to work together.”

The district has been fortunate most the individuals who contracted the virus have fared well, he said. A senior in the spring became very ill due to underlying health issues, but now he is recovered and enrolled in college. Still, Hoadley said he worries about potential long-term issues for those who get sick, in terms of possible heart damage or lung damage.

Due to the rise of local COVID-19 cases in Dublin, the school recently postponed its plans to return to five-day in-person learning. While the cases in the school community are concerning, Hoadley said students are safe in the classroom with the precautions in place.

Less than a week from the election, the presidential candidates are offering competing messages on the issue of reopening schools, a key election issue for many voters.

President Donald Trump calls for local officials to “Open the schools” citing low transmittal rates to teachers. Under a Joe Biden administration, school districts would face less pressure to offer in-person instruction during the pandemic. The former vice president said he would issue national guidelines that tie school reopenings to local COVID-19 numbers.

Bill Wise, superintendent of the South-Western City School District which records 84 infections, shared Hoadley’s assessment of how students are getting sick. “In the vast majority of our cases, it's not occurring within the schools to the best of our knowledge,” he said.

While the district has the second most cases in the state, Wise said the return to in-person instruction with a hybrid model has actually gone better than he anticipated, stressing the rate of infection is minuscule with the infections coming from a student and staff population of about 25,000.

“We haven't seen significant increases. We've seen increases outside of our school community, but those really at this point haven't trickled into our school community,” Wise said. “Transmission student-to-student, our contact tracing would not support that that's a significant number by any means at this point.”

Amber Pasternak, a mother of twins in first grade, juggles her own job as a program manager at an Ohio State research center with the challenges of getting two little ones on-task with their virtual coursework.

In the mornings, her kids, who are students at Salem Elementary School in Columbus City Schools, log on for several hours of synchronous online learning with their teacher.

She structures her workdays so she can spend the mornings when she is supervising her kids’ virtual learning, working on things “that don't require heavy thinking,” like sending emails and responding to quick questions.

“First grade is rough. Getting them to focus and pay attention through the screen is a challenge, so I do think that at least some amount of in-person learning would be good for them, and me. But I also want it to be as safe as possible when they go back,” Pasternak said. “I look forward to a day where my kids could be in school at least part of the time, but I really don't want it rushed.”

For their asynchronous learning in the afternoon, her kids do not usually need as much oversight, so Pasternak uses that time to get deeper into work projects. If they do need help with the asynchronous work, she says they do it together in the evening, treating that time like how they used to do homework after dinner.

Columbus City Schools had planned to switch to a hybrid learning model in the fall after starting the term virtually. But record COVID-19 numbers in Ohio put those plans on hold.

Ohio schools have reported 5,058 COVID-19 cases this fall among students and staff. The numbers do not include students at virtual learning schools who were not on school grounds while they were infectious. On Oct. 29, the Ohio Department of Health reported more than 1,232 new school cases, the largest increase since the state’s dashboard was released on Sept. 17, and the second consecutive week with more than 1,000 cases.

Pasternak is exhausted from supervising school-from-home while working full-time, and her kids are not thriving in the virtual learning environment, though with the COVID-19 numbers in the past couple weeks she is not sure if Columbus is in a good place to go back to school.

Going back to school five-days a week in a district as dense as Columbus would be irresponsible, she said. However, some of her friends have kids in hybrid models and tell her it is going well. But how that would work in the state’s largest district still feels complicated.

“There obviously are districts that are making this work, and we don't hear about a lot of spread at school of the virus, so I think a hybrid model could be good. But I think also there needs to be a lot more communication about how the day looks like, you know, how are bathroom breaks handled? How is lunch handled? Are the kids really spending a whole entire day at one desk in the classroom? Is there time to go outside?”

And what happens when kids need help getting their shoes tied? Or putting their masks on, she wonders.

“I do think that there are kids, mine included, who aren't excelling, necessarily, in the virtual environment. As long as it seems like being home is the best option, I'm willing to keep doing that. But whether it's because of learning differences or family situations, virtual isn't necessarily working for everybody.”

Cathy Felty, a multiple disabilities teacher at Oakmont Elementary School in Columbus, said many students can learn well virtually and are thriving in this environment, but other students, particularly those with different learning styles, are having a difficult time. Many of her students really need “paper and pencil” instruction.

“They are hands-on concrete learners, and they learn best in the classroom,” she said. “But you have to balance that with the safety of the students.”

Teaching young students with learning challenges, the biggest struggle can be the use of technology and oftentimes it takes parents sitting next to their kids for instruction in the virtual model to be successful.

Each Friday, Felty and her instructional assistants pay visits to all their students’ homes to drop off packets with learning materials for the following week. More than 24 years into her career teaching, this is her first in Columbus, and seeing her students in-person, if only briefly, helps build relationships that are otherwise maintained only through the lens of a camera.

As the coronavirus outbreak worsens, Felty said all she can do is take it one day at a time.

“We don't know what's going to happen tomorrow, we can only plan for the information that we have today. And we just have to go day-by-day and see, just keeping foremost in our minds that the education of our students is a priority and the health and safety of our students is a priority.”

Columbus’s case occurrence is considered “high incidence,” but it is now in the bottom half of Ohio’s 88 counties as infection rates have become more concerning rurally. Asked why Columbus postponed its return to a hybrid-learning model, Health Commissioner Mysheika Roberts acknowledged “the data does show that kids are safe in the classroom,” but said district officials consider it a challenge to safely move 50,000 students back to school due to the size of the district’s operation.

Hoadley said he believes hybrid learning could work anywhere, as evidenced by the lack of infections in his district’s classroom despite spread in the community, but he acknowledged that he has not worked in a big urban district. And while he feels it is safe from a health standpoint, hybrid learning is quite demanding of teachers, he said.

“We're working people like crazy right now. My biggest fear is how sustainable this would be. I think we can get through a school year, but we're going to lose people just to exhaustion,” he said.

Gov. Mike DeWine says it should concern all Ohioans that so many schools are online, an environment he says is less conducive to effective learning for many students, especially for Ohio children in poor households.

According to an Oct. 21 Spectrum News/IPSOS Poll, 46% of Ohioans say children have fallen behind in school due to COVID-19 and more than half, 54%, believe their child would be safe to attend school in-person.

School officials have crunched academic testing numbers for the South-Western City School District, finding that virtual learning has caused students to fall behind the most in mathematics, Wise said.

Fall diagnostic testing showed virtually no change with language arts as compared to expectations from previous years, he said, a sign that spring virtual learning was effective in those areas. That was not surprising because online learning can tend toward a text-based and writing-based curriculum, he said.

“Our results for language arts were within 1% of where they were a year ago. We didn't make growth, but we didn't lose much ground either. In the area of mathematics, it was different, we saw roughly a 9.4% decrease in the skills for our students this fall, from the previous fall. And we do think that was in large part because of the fact that we weren't able to work with students individually. It's just much harder to see the mistakes and listen to them as they mentally process in a virtual world than in a classroom.”

In Dublin City Schools, Hoadley said it is art, music, and physical education, which are being offered virtually, that have been set back the most with their hybrid-learning model. For elementary students, the district is using an “a.m./p.m.” model, in which students are in the classroom for core academic subjects for half the day in one of two sections, and online for the other half, rather than a 2-2-1 model where students are on campus for particular days of the week.

“We are shortchanging those related arts, so our well-rounded education is getting a big dent in the side of it. But as far as the core academics at the elementary, I think we're more than getting the job done there,” Hoadley said.

For middle and high school students, mental health has become an area of major concern in Dublin. Those older students are struggling with the lack of personal connections and the lack of connectedness with school, he said. Grades are also a source of heightened stress, especially for students trying to bolster their resumes for college while only getting half as much in-person instruction as normal. Two days a week of learning when you are taking multiple AP classes is just not enough, he said, and that's causing a lot of anxiety.

“We are maybe treading water, maybe,” Hoadley said. “But the long term learning gaps in K-12 scare me to death right now. I am really worried what the lives of some of our children that, right now, are just not getting the education they need, where will they be in 10 to 15 years because of just not having the foundational skills for success?”