LOUISVILLE, Ky. — Each day after she clocks in at a Central Kentucky clothing warehouse, and again before leaving, Caren Lamblin sanitizes her workstation. Even as safety protocols are relaxed — now that she’s fully vaccinated, Lamblin is allowed to work without a mask — it’s a ritual that lives on.

“It used to be, if you got a chance to wipe off your counter, great,” Lamblin said. “Now it’s the first thing you do and the last thing you do. It’s normal now.”

After nearly a year and a half of working under unprecedented pressure, essential workers are now experiencing a host of changes to their work lives. Employers are emphasizing cleanliness and offering higher wages, with workers gaining more power than they had before the pandemic. As the COVID-era starts to fade, along with the notion that front-line workers are “essential,” several Kentuckians who never stopped reporting to work during the pandemic told Spectrum News 1 that they hope many of these changes are here to stay.

“I do have a sense that the ball is starting to be more in the worker’s court, rather than the company’s,” said Mason Sims, who worked at Kroger throughout the pandemic. “But I don’t think we're fully there yet. We’re still struggling on the front lines.”

Throughout the pandemic, some companies helped ease that struggle by offering hazard pay and bonuses. Those eventually expired, but the idea that workers were worth more than they were getting did not. Soon, McDonald’s, Costco and Walmart were among the major employers to announce hikes in their minimum wage. Some other companies, including Louisville’s largest, UPS, followed suit as the labor market tightened this summer.

Sims, who recently left Kroger to take a higher-paying position doing the same work for a different company, said employees understand their worth better now than they did before the pandemic.

“No one is going to want to come back to a job that pays less than $15 an hour to be yelled at and treated like crap,” he said.

While some people move to better-paying jobs as essential workers, others have left the front lines entirely.

That’s what Noah Smith did. After several months last winter working the counter at Breadworks, a Louisville bakery, Smith began a job at the University of Louisville in February. It’s the type of position that doesn’t require confronting cranky customers or fighting for tips. “I will never, never go into a work setting like that again,” Smith said. “It's not worth it to me.”

Chris C., a former Amazon employee who asked that his last name not be used, also left the front lines. After working in a warehouse for several months this year, coming home each day with sore feet and frayed nerves, he moved to a new position in data analytics, the field in which he hopes to spend his career.

These two Kentuckians are part of a national wave of workers evaluating their jobs and deciding to move on. A record four million Americans quit their jobs in April, according to the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics. The number dropped to a still-high 3.7 million in May. Stats show that many of these workers are leaving the front-line fields that never stopped during the pandemic, with retail, warehousing and food services among the sectors with the most departures.

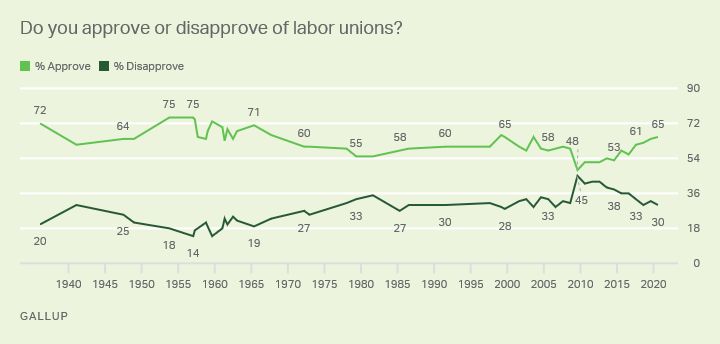

Union membership in the U.S. fell once again in 2020, the continuation of a decades-long trend. But due to higher job security for union members, the share of all workers who were in unions increased.

Now, some experts think the pandemic will lead to an increase in overall memberships. “The minimum wage remains at a measly $7.25, and the pandemic revealed that neither Federal or State OSHA are staffed and equipped to ensure the safety of workplaces,” said Ariana Levinson, a labor law scholar at the University of Louisville Brandeis School of Law. ”When workers are working in unsafe conditions for low wages, there will be an increase in unionization.”

Nonunion workers also saw unions step up for those on the front lines in the early days of the COVID outbreak. Before the pandemic was a month old, the United Food and Commercial Workers negotiated higher pay and improved benefits for meatpacking workers. Within days of the COVID’s arrival in the U.S., the Teamsters reached an agreement with UPS to provide sick leave to workers. By late summer, a Gallup survey found support for labor unions growing, with 65% of people saying they approve, the highest number in two decades.

None of this was enough for the most high-profile pandemic-era union drive to succeed, though. In March, workers at an Alabama Amazon warehouse launched a union drive that failed in its ultimate goal but inspired some Amazon employees in Kentucky to think about how a union could help them.

Few essential workers experienced the pandemic like nurses, who remain on the front lines as the Delta variant drives cases upward. Now, many are considering leaving the job behind. In April, a poll from Vivian Health, a job marketplace for health care workers, found that 43% of nurses are thinking of leaving the field in 2021.

Carolyn Tinsley, a nursing instructor at Murray State University who worked in a COVID-19 ICU last year, has some insight into why. Tinsley said her COVID-19 patients were “the sickest people I’ve ever seen in my life.” Treating them was grueling, she said, and required nurses to make great personal sacrifices.

On top of the physical and emotional toll, she felt like people weren’t listening to nurses. That's something she hopes changes in post-pandemic America.

“Nurses can help to teach the public,” she said. “Nurses are good at communicating and I think people trust nurses more than other people.”

In the early days of the pandemic, celebrations of essential workers were largely ceremonial. Now some states are celebrating these workers with programs that aim to improve their lives.

In recent months, several states have enacted measures aimed at rewarding essential workers for their sacrifice. Michigan’s Futures for Frontliners program provides free community college tuition to front-line workers who worked outside of the home between April 1 and June 30 last year. In New York, essential workers can apply for child care scholarships.

Kentucky, meanwhile, has not enacted anything similar. But that could change early next year when Gov. Andy Beshear has said he will encourage the General Assembly to pass an "essential worker bonus."