MILWAUKEE — So, 2021 didn’t turn out to be the year we ended the COVID-19 pandemic.

As we head into the new year, the novel coronavirus is surging once again. Despite the deja vu, though, we’re not in the same spot as before: We’ve uncovered a lot about COVID-19 in our second year of living with it.

“I think we've accomplished a lot in 2021,” said Joyce Sanchez, an infectious disease specialist at Froedtert and the Medical College of Wisconsin. “We still have a considerable amount of work to do as we enter 2022 together.”

From alpha to omicron, vaccines to boosters, scientists have been working hard to understand — and hopefully bring an end — to the pandemic.

Last year, we took a look at the lessons from the pandemic’s early days. Now, we’re following up with Wisconsin experts to break down some of the biggest 2021 takeaways — and what could be coming our way as we head into 2022.

Where we’ve been

Thinking back to the start of 2021, UW-Madison epidemiologist Ajay Sethi remembers one big emotion.

“Around this time last year, I think there was a lot of hope,” said Sethi, an associate professor of population health sciences. “That the vaccines were approved, and the rollout was beginning, and that it was going to return us to normal.”

When the year kicked off, the U.S. was just starting to deliver COVID-19 vaccines to priority groups, like health care workers and the elderly. Over the first few months of 2021, more shots rolled in, and more people were able to roll up their sleeves. By April, the vaccines were open to the general public.

But after a few weeks of the initial rush, our demand hit a “brick wall,” Sethi said.

“Suddenly, it was very difficult to get people to get vaccinated,” Sethi said. “And I think that was quite a blow to the hope that people were having.”

For Oguzhan Alagoz, who’s been involved with modeling the spread of the virus, the vaccine rollout highlighted a big takeaway from earlier in our COVID-19 fight: Human behavior is key.

Even great science can only make a difference if the public is onboard, said Alagoz, an industrial and systems engineering professor at UW-Madison. Now, we’ve ended up with a “tale of two pandemics,” he said, with new surges hitting unvaccinated people the hardest.

“My first year sort of primary lesson was if you want to fight the pandemic, we’ve got to first make sure that the community is on the same page,” he said. “And the second year, we have seen that with vaccination, too.”

Another important lesson from the past year: The virus can, and will, keep changing on us.

From alpha to delta to omicron, new variants of the SARS-CoV-2 virus have kept experts on their toes throughout 2021. As variants have gotten more infectious and cut down on incubation times, they’ve challenged our ways of managing the spread, Sethi said.

With omicron, “there's this feeling of inevitability, that most people feel like they're just going to have to deal with a breakthrough infection at some point,” he added. “I don't think delta gave people that impression.”

Though some of our early-2021 optimism may have faded, Sethi said there are silver linings in the age of omicron. So far, research has shown that infections with the newest variant seem to be more mild, with less risk of hospitalization.

And even dealing with “bigger, badder variants,” vaccines have held their own against severe disease, hospitalization and death, Sethi pointed out.

This time around — unlike in earlier surges — many people’s immune systems have gotten the chance to build up their defenses to protect against the worst COVID-19 outcomes, Sanchez said.

In that sense, she said, “this gift of a year's time has been on our side, especially now, in the midst of an omicron firestorm.”

Where we’ve stumbled

There was a lot of progress in how we talked about COVID-19 in our second pandemic year, said Dominique Brossard, chair of the Life Sciences Communication department at UW-Madison. But some of her concerns from the early days still tripped us up in 2021.

“I was worried that COVID would become very polarized,” Brossard said. “Well, it did happen.”

Looking at vaccination as just a political issue — instead of addressing all the different reasons people might be hesitant — has been “really bad for the health of the nation,” Brossard said.

Misinformation is another big, disheartening piece of the puzzle, Sethi added. The vaccine rollout has run into problems here — not just with people who “live in a bubble” of incorrect news sources, but also with those who deliberately spread bad information, he said.

“That really just needs to be addressed,” Sethi said. “Otherwise, we're going to move forward in this purgatory of never being able to manage this pandemic.”

Generally, there’s a fine line to walk to keep people informed during the pandemic, and we didn’t always strike the right balance in 2021, experts said.

On the one hand, Brossard said, it’s not productive to only focus on the negative, like going back into “panic mode” with the arrival of the omicron surge.

Our “negativity bias” may come from “biology that told us we should run away from danger,” she said — but “we need to realize that that can also increase fear and panic and bad behavior.”

Still, tthere are risks with painting a too-sunny picture, too.

For example, Alagoz worries that we oversold how vaccines would bring a quick end to the pandemic. When we saw the super-high efficacy rates for the shots, we loosened up our precautions and got back to more of our lives, Sanchez pointed out — but later realized that the variants would put a damper on that efficacy and a hitch in our “new normal.”

“That's a lesson that has humbled us once again,” Sanchez said.

In the end, Brossard said, there’s still room to be more honest about the uncertain nature of our scientific process. Even large agencies, like the CDC or the WHO, have fallen into the trap of presenting COVID-19 science as more certain than it is, she said.

“People do not like the unknown,” Brossard said. “They do not like to find things out at the last minute. They do not like to feel that they've been lied to, or that people are hiding things from them. So, you know, it's much better to be transparent.”

Where we’re heading

With the added factors of vaccines, boosters and multiple variants going around, Alagoz said it’s gotten “exponentially more difficult” to model where our pandemic trends are going.

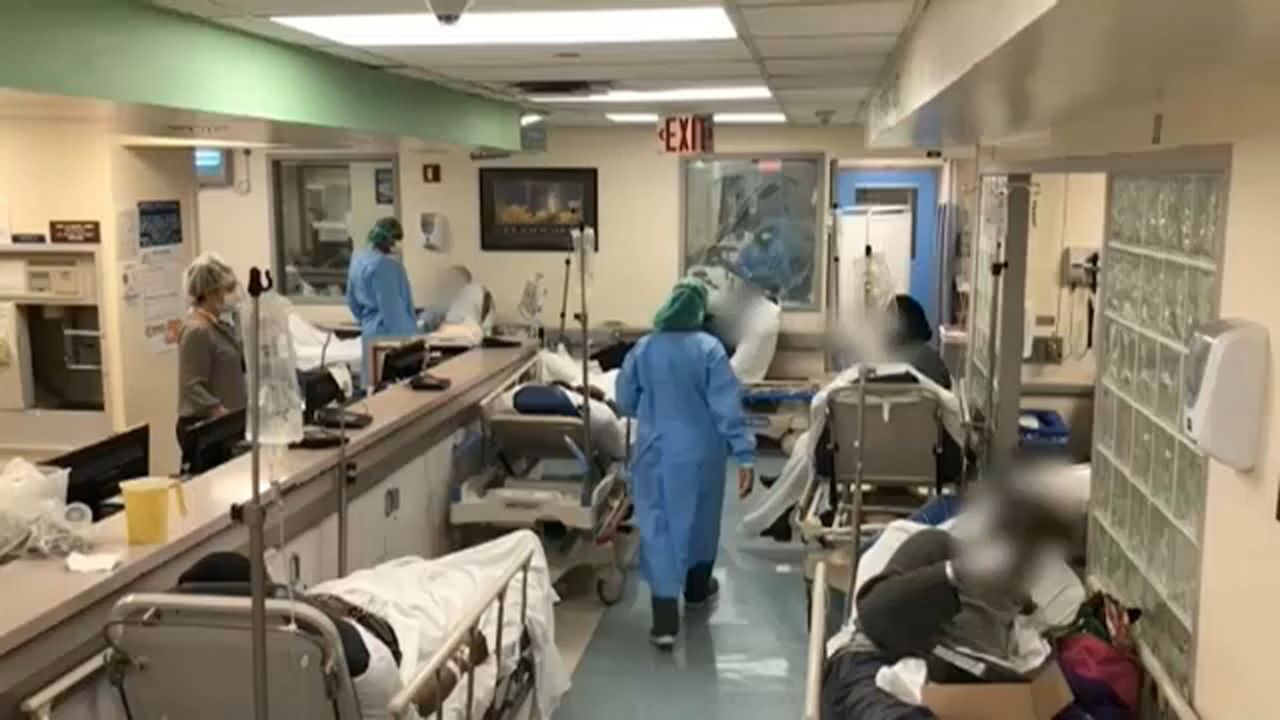

He’s definitely worried about the next few weeks, as we kick off 2022 with record case numbers and overflowing hospitals. But our steep climb in infections could be followed up by a quick dropoff — something that South Africa experienced with its own omicron wave.

“I am hopeful that after that, you know, things are going to be under control,” Alagoz said.

Of course, a lot of that future depends on what kinds of new variants we see emerging this year, Sethi said.

There’s a chance that new versions of the virus could push omicron out or spread alongside it, he said. And while the virus may become more endemic in the future, there’s no guarantee that every new variant will be less severe than the last, he explained.

“When it passes on to a new host, I don't think the virus, if it had feelings, would really care about what happens to the host it just infected,” Sethi said. “As long as it's able to pass from one person to the other.”

The variants’ huge effects have highlighted that our fight against COVID-19 needs to take place on a global scale, experts said. As long as the virus is still spreading in some parts of the world, it can keep changing and posing a threat to people all over, Sanchez said.

“It's just not enough to control disease in one part of the world and then forget about other parts,” Alagoz said. “Infectious diseases do not know borders, unfortunately, especially in a globalized world.”

Another finding from 2021 — that white-tailed deer can harbor the SARS-CoV-2 virus — means we should even be keeping an eye on other species, Sethi said.

There’s no evidence so far that deer can spread the virus back to humans. But if that turns out to be the case, that’s bad news for the idea of “herd immunity” against COVID-19, Sethi said, since animals could keep the virus circulating and mutating into new forms.

Even if we’re living with the virus for a while, Sethi said he’s hopeful that things will start feeling more manageable if we’re able to flatten the curve and protect our health care systems.

“Society won't feel normal if you need health care and can't get it because beds are full,” Sethi said.

That means finding new ways to break down barriers for those who are still vaccine hesitant, Sanchez said, and doubling down on the mitigation measures we now know well.

In some ways, we’re in a much better place today than in 2021, since many people are protected by the vaccines, Sanchez said. But health care workers have been in a state of chronic stress for a long time now, she pointed out, and suffered a lot of “moral injury” after another year with COVID-19.

People in general are dealing with a lot of pandemic fatigue, Brossard added. Heading into the future, we’ll need to pay attention to the toll these years have taken — even once the pandemic comes to a close.

“How can we build resilience again?” Brossard said. “How can we build a better future, a better community, a better society where we live together, when we move the page? Because we will.”