MADISON, Wis. — As students returned to UW-Madison’s campus last fall, in the midst of the ongoing COVID-19 pandemic, tensions were high.

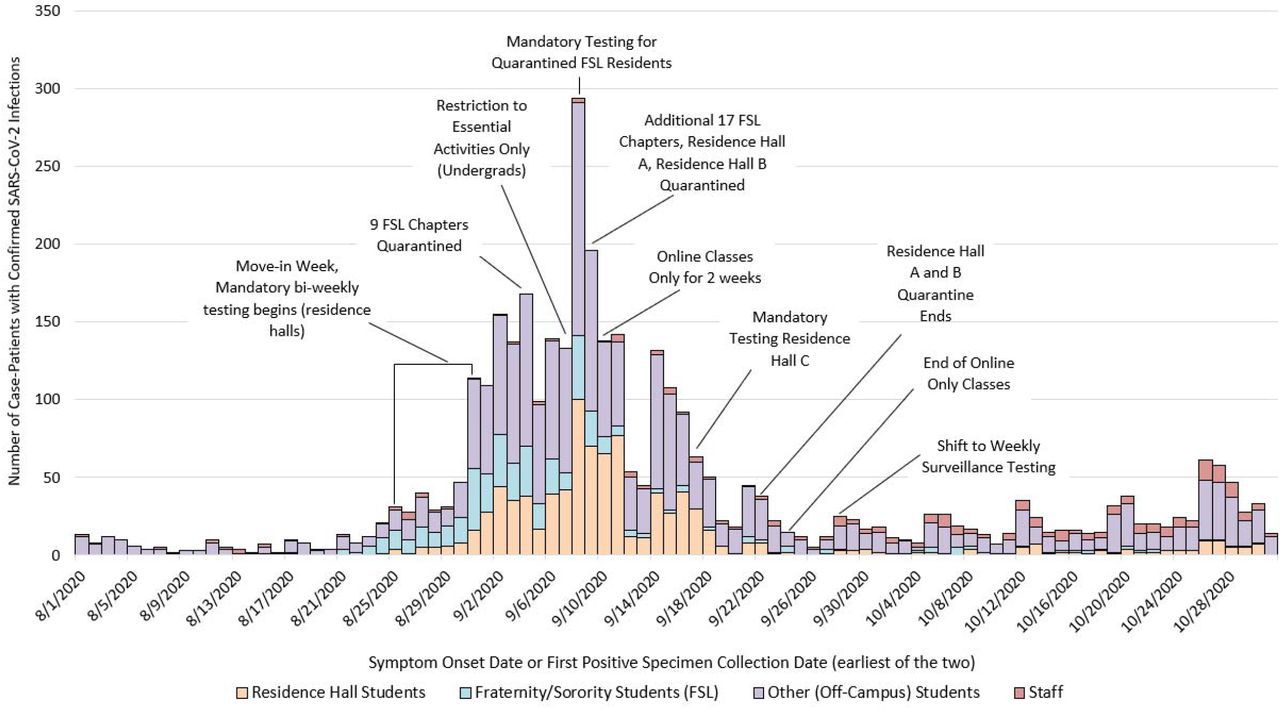

Cases quickly started to rise, especially in Sellery and Witte residence halls — the two biggest dorms on campus. With hundreds of students testing positive each day, residents feared the outbreaks would leak out into the surrounding community.

“Everything was really ripe for there to be this big spillover,” said Gage Moreno, a recently graduated Ph.D. student in virology.

But in a recent study — published online in preprint form last month — UW-Madison researchers, along with the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, came to a conclusion that surprised them.

The outbreak in Sellery and Witte, which infected hundreds of students and sent many more into quarantine, didn’t seem to spread into the wider Madison area, according to genome sequencing data.

“We've been conditioned to really expect the worst. And so before we started sequencing, all of us really thought, ‘Oh, God, this is going to be terrible,’” Moreno said. “The fact that we didn't see that happen was really shocking.”

Moreno worked as part of virologist Dave O’Connor’s lab, which has sequenced thousands of coronavirus samples since early on in the pandemic. From the swabs that go up people’s noses, the researchers extract viral RNA, convert it into DNA and then map out all the nucleotides that make up its genetic code — which for SARS-CoV-2 is about 30,000 letters long.

Because the virus is constantly mutating, each sequenced sample creates a “genetic fingerprint” with its own set of quirks, Moreno said. Scientists can then compare the fingerprints between infected people to see how closely linked their cases might be.

“Each individual’s virus is unique in a specific way,” Moreno said. “When they look very similar, we can say, ‘Hey, those are linked by a transmission chain. They're transmitting to one another.’ But if they look really different, we're like, ‘Oh, those are two different outbreaks.’”

For this study, the researchers looked at 262 samples from campus and 467 from the rest of Dane County taken between August and October.

Around two-thirds of the sequenced samples from Sellery and Witte shared a particular mutation on the virus’s spike. That mutation hadn’t been seen before in other Dane County samples, Moreno explained — so if it showed up in cases later on, it would be a telltale sign that the campus outbreak was the source of spread.

But even after months of continued sequencing, the team didn’t see the dorm outbreak’s signature mutation crop up in the wider community.

The genome sequencing confirmed what researchers had already seen in the case data, said Brian Yandell, a UW-Madison statistics professor who also contributed to the study.

Yandell, who’s been helping advise the campus COVID-19 response team, said that in the weeks after the dorm outbreaks, they didn’t see a huge explosion of cases in the broader community.

So, looking at the case counts and the genetics, “we can say with relative confidence that the dorms, Sellery and Witte, did not contribute to the outbreak here,” Moreno said.

The campus’s quick response may have helped keep the outbreaks from spreading beyond the dorms, Yandell said. As cases skyrocketed in Sellery and Witte in September, the school ordered everyone in those residence halls to quarantine in place for two weeks and put in-person classes on hold.

“By putting those infected in isolation, and those who were exposed in quarantine, they were able to basically shut off the track of infection,” Yandell said.

But Moreno pointed out that some of it just comes down to chance: All the conditions were there for the dorm outbreak to break loose into the community, he said.

“I think that there was a really big component of luck,” Moreno said.

It’s hard to generalize these findings to other campuses, he added. Every campus is different: In Madison, for example, the campus is mainly downtown and separated from other parts of Dane County that skew toward older residents, while students at other schools may interact with the community in different ways.

Even within UW-Madison, the findings were pretty specific to students living on campus, said Paraic Kenny, the director of the Kabara Cancer Research Institute at Gundersen Medical Foundation in La Crosse.

Kenny has also been running genome sequencing on coronavirus samples in his community. And in a study last fall, his team found that cases among college students living off campus — including those from UW-La Crosse — did lead to other infections in the area, including in local nursing homes.

Compared to students in relatively contained dorm settings, off-campus students might actually be “a bigger reservoir of risk for the surrounding community,” Kenny said.

Still, he said his research and the UW-Madison are generally in agreement: It’s important to take seriously how specific outbreaks can put the whole community at risk.

“Our broad conclusion is that when COVID-19 was allowed to get out of control in any setting — whether that was a university, a meatpacking plant or other settings — we’re all connected, and at some level of risk,” Kenny said. “In ways that, you know, were probably not very widely appreciated prior to the pandemic.”

The UW-Madison study also found that students with roommates were more likely to test positive, and a lot of the viruses between roommate pairs had identical genomes — suggesting that in many cases, one roommate infected the other, or they caught the virus from the same place.

And across Sellery and Witte, genetic sequences looked pretty similar, according to the study, so the outbreaks probably involved a lot of mixing between the two dorms.

Since those early days in the fall, the school has seen its case counts drop off significantly. In the last week of May, campus testing only returned one positive result, according to the university’s COVID-19 dashboard; the weekly positivity rate hovered below 1% for almost the entire spring semester, as the Wisconsin State Journal reports.

Yandell said a lot of effort went into building up the campus response, like ramping up regular testing for residence halls and increasing contact tracing capacity.

And Kenny said Wisconsin was lucky to have some labs that were equipped to help out with genome sequencing to fight COVID-19. Though genomic surveillance has ramped up across the country, early on in the pandemic there were “vast black holes” without any sequencing data to lean on.

Dane County, on the other hand, has been one of the most sequenced places in the U.S. over the course of the pandemic, Moreno said. Sequencing is an especially important tool when it comes to a virus like SARS-CoV-2, whose asymptomatic spread can make traditional contact tracing tricky, he added.

Even through the exhaustion and intense workload — his longest day was around 19 hours in the lab — Moreno said it’s been rewarding to serve as part of the public health effort. He’s hopeful that looking toward the future, genome sequencing can help craft a more targeted approach to tackling disease outbreaks.

“Now that there's sequencing, and a way to do this enhanced contact tracing, there's room for precision public health,” Moreno said. “Where you're able to really look at these tiny pockets of transmission, and act quickly to stop those outbreaks from getting bigger or spilling out.”