MILWAUKEE — The battle over Wisconsin’s political boundaries has been years in the making. Republicans drew the lines in 2011, and several lawsuits by Democrats were unsuccessful until recently.

Challenges over what Democrats had long insisted were gerrymandered lines started to culminate in 2021 when Gov. Tony Evers vetoed the latest Republican-drawn maps and insisted the legislation amounted to “gerrymandering 2.0.”

That move led to even more lawsuits. Two years ago, the Wisconsin Supreme Court had sided with Evers only to reverse their decision after the U.S. Supreme Court struck down the lines based on the Voting Rights Act.

At the time, it was a victory for Republicans, who had a decent chance at winning a veto-proof majority in the Legislature.

However, just a year after all that unfolded, Democrats would get their victory by flipping the ideological balance of the state Supreme Court for the first time in 15 years.

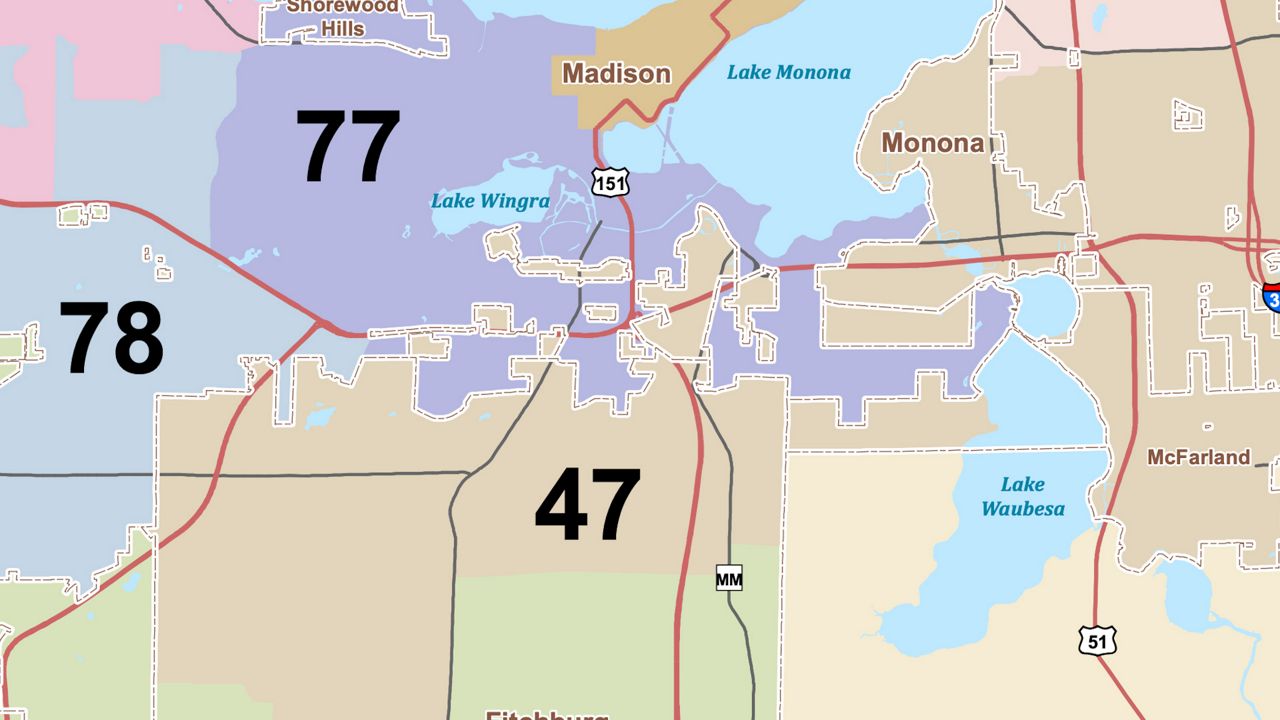

With liberal-learning Justice Janet Protasiewicz on the bench, a lawsuit was filed in August, that ultimately led to a 4-3 ruling in December in favor of Democrats who argued the GOP legislative maps were unconstitutional because districts weren’t contiguous.

About a month later, the Senate passed new maps, which the majority leader insisted were “99.7%” of what the governor proposed.

A day later, the Assembly followed suit, with all Republicans in support and all Democrats against. The governor, however, would go on to veto those lines, calling them “bastardized.”

Evers said the political lines weren’t his maps because Republicans had scaled back the number of incumbents in their party who would have to face each other in November.

It ultimately became a last-ditch effort on Feb. 13 as the Republican-controlled Legislature passed exactly what the governor had proposed, with the hopes of avoiding court intervention that could be even less favorable to their party.

Less than a week later, the governor signed those new boundaries into law. However, not everybody was happy—many Democrats saw it as a too-good-to-be-true moment and questioned whether Republicans had planned to take the battle to federal court instead.

Unlike in 2020, when the maps were drawn a decade earlier, Republicans had control of both the Senate and Assembly, as well as the governor’s office, which gave the party total power over the process.

Some Democrats said maintaining majorities got in the way of the goal: “one person, one vote.”

“I think the impact is seismic,” Dan Lenz, an attorney with Law Forward, said. “We haven’t had opportunities for both parties to compete on our maps for over a decade.”

The Madison-based firm is a nonprofit with the stated goal of protecting democracy. Last August, just a day after Justice Protasiewicz was sworn into the state’s high court, the firm challenged the existing GOP maps.

“This case tested new questions about what our state constitution had to say both, initially, about political gerrymandering, and then also about the meaning of our contiguity provisions and how our districts are supposed to look,” Lenz explained.

Under a new liberal-learning majority, the court agreed to hear the case, and while several claims were made, including a separation of powers violation, justices focused on contiguity—those detached pieces of territory.

“The contiguity issue was the fig leaf to cover up what the court really wanted to do, which is a dramatic redraw of the state,” Luke Berg, an attorney with the conservative Wisconsin Institute for Law and Liberty (WILL), countered.

Berg said that even though there is a contiguity requirement, and nobody disputes the existence of those disconnected pieces, previous state and federal court rulings have allowed those districts under certain circumstances—typically an effort to keep towns, cities, and villages with annexed pieces together.

“Law Forward filed this new case, and one of their theories was, ‘Oh, we’re changing our view on what contiguity means, and now we’re saying that you can’t actually have these islands’ even though they had just taken the position two years ago that you could have these islands,” Berg said.

“Folks have been challenging those maps, more or less, the whole time,” Lenz insisted. “It’s not as though anything was new here. I mean, the questions that we raised to the court were novel, but I don’t think anyone should have been surprised that there was going to be a challenge to these maps again.”

Berg believes there was a simple fix of just absorbing or connecting those so-called “islands” to surrounding districts, which are often sparsely populated.

“If you read the opinion, there’s a single sentence in there where the court says, ‘Oh, the contiguity problems are so pervasive in all the districts that it would be too complicated to resolve it by absorbing the islands’ and that’s just simply not true,” Berg added.

Lenz, however, said with more than half of Wisconsin’s districts violating that basic rule, something had to be done.

“In many ways, this is what our system is supposed to do,” Lenz stated. “We’re supposed to have, you know, meeting of the minds, some sort of compromise, so we’re very happy with that. The governor’s maps are fair maps. That’s what the consultants told us. That’s what we have said.”

In the end, Republicans who control the Legislature gave in, but Berg said that’s only because they were backed into a corner.

“The governor’s map was the least bad Democratic gerrymander, and so they just thought let’s adopt that because we might get a worse outcome if we keep going with the case,” Berg concluded.