Ohio is one of the most interesting states to forecast the weather for. While there are many meteorological factors to consider, one geographical one that can truly change things is Lake Erie.

What You Need To Know

- Lake-effect snow is a common occurence in the wintertime

- Lake-effect rain, while rarer needed more instability in the milder months

- Ice over Lake Erie can inhibit snow band development

- Warmer observed lake temperatures means increased snow potential

In the summer, cool breezes off the lake will keep the temperatures down in places like Sandusky, Cleveland and areas far north and east like Ashtabula. This influence of cooler, Canadian air makes resort towns and lake-side getaways ideal for those in the surrounding areas that can experience hot and more humid weather.

But in the winter, those colder breezes can create massive amounts of lake-effect snow that can shut down cities and create traffic nightmares. Let's start with the basics:

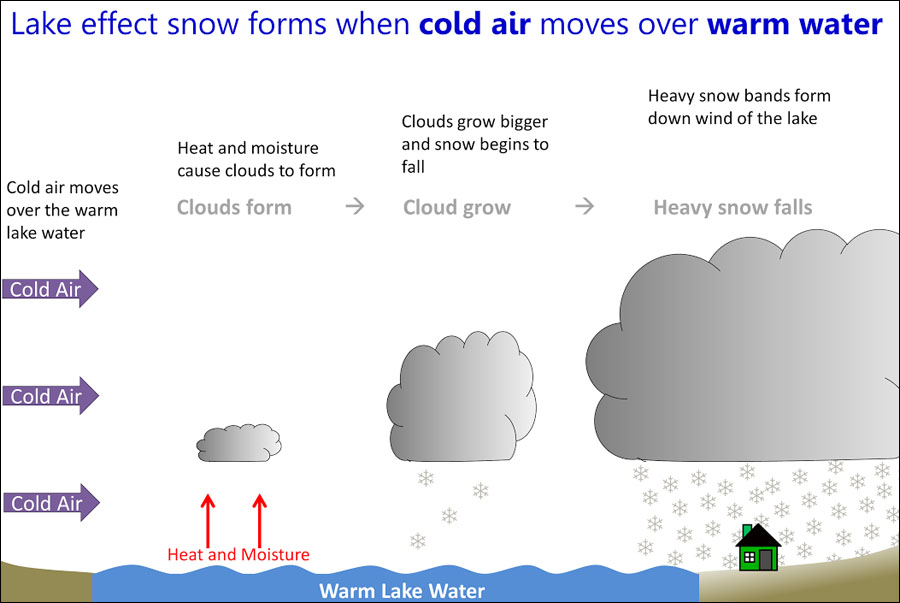

In the late fall, winter, and early spring, cold Canadian (sometimes Arctic) air moves south and across the Great Lakes. In Ohio, these winds cross Lake Erie, which has water that is warm relative to the cold air surrounding it.

These winds help transport the warmth and moisture of the lake into the lower levels of the atmosphere, eventually creating quick-forming clouds and precipitation.

There's a lot of atmospheric instability here, which helps to form these conditions in such a short amount of time. Often, these bands are narrow and continually form, dumping feet, not inches of snow in many instances over areas on and along the lake.

Geography plays such an important role in which areas get the heaviest snow.

Cleveland, for example is indeed along the lake, but the true "snow belt" along I-90 and areas like North Perry, Geneva-On-The-Lake and Ashtabula are positioned more eastward. The general movement of the air carries heavier and more frequent bands of snow their way.

This is an interesting topic to discuss. To date, Lake Erie has only frozen over completely frozen over in 1978, 1979 and 1996, according to the National Weather Service, which started observing such conditions in 1973.

In those rare instances, lake-effect snow is limited or even stopped.

With no open water and all ice, the moisture-supply is essentially "cut off." But even a partial ice-cover can greatly affect lake-effect snow formation. The larger the area of frozen lake, the less likely the atmosphere is to absorb sufficient moisture to create snow.

Short answer: Yes.

Generally, many of the atmospheric conditions are the same for lake-effect rain. The best time of year to see this is the late summer through the early fall. But there's more of a difference than just temperature.

For lake-effect rain, a bigger trigger is needed to cause the precipitation. This can include an area of low pressure or a powerful front from the northwest. The air moving over the lake must still be cooler than the water, but now we need some conditionally unstable variables.

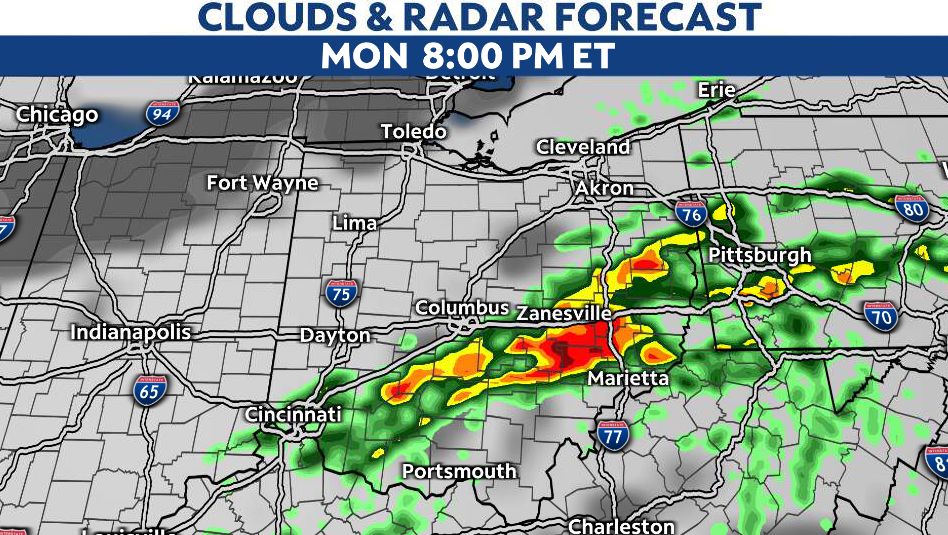

Think of this as the atmosphere needing to "raise the bar." As such, oftentimes it's not just plain old rain, but thunderstorms that can develop and even become severe that form over the lake.

In the summer of 2020, multiple waterspouts formed over Lake Erie, something not entirely rare.

While the frequency of the snow bands and intensity can greatly vary from event to event, recent observations have shown an increase in activity.

And although one might want to look at the sky and wind direction for answers, the reason may be rooted in the lake and surrounding temperatures.

High resolution models have been studying the lake temperatures, which have been slowly increasing over the years. This creates a variety of situations where due to a lack of ice cover, and higher differences between air and lake temperatures, increased snowfall may occur.

With land temperatures increasing as well, we very well might also see more instances of wintertime lake-effect rain, rain/snow mix and perhaps even freezing rain – something we've already observed this winter season.