WASHINGTON, D.C. — Members of the Ohio Farm Bureau visited Capitol Hill this week to meet with lawmakers and discuss the farm bill—a sweeping package of legislation to set policy and funding levels for farm, food and conservation programs.

What You Need To Know

- Members of the Ohio Farm Bureau were in Washington, D.C. this week to advocate for new measures in the next farm bill

- The farm bill was last updated in 2018

- Lawmakers say they're confident they can pass a new bill this year

The farm bill is usually renewed every five years and was up for reauthorization in September 2023. However, as lawmakers were preoccupied with avoiding a government shutdown and passing a foreign aid package through the fall, they instead extended the old farm bill another year.

Since the last farm bill was passed in 2018, global events like the COVID-19 pandemic and Russia’s war against Ukraine have changed the global market and raised costs associated with farming.

Ohio farmers want the new farm bill to address current concerns.

“It’s the largest economic driver for the entire state of Ohio so it deserves the attention we’re asking for,” said Ty Higgins of the Ohio Farm Bureau. “We’re going to see a decrease projected of 25% in farm income in 2024, so these things are important to keep the farms going for many generations to come.”

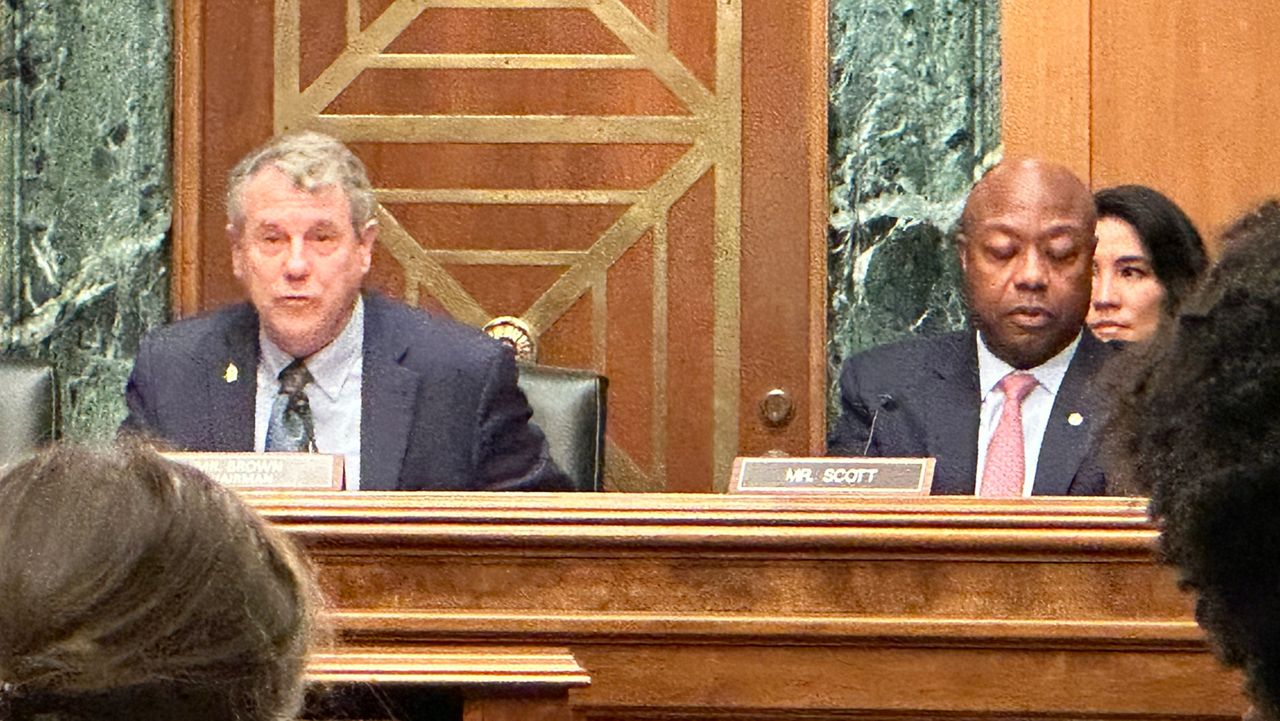

Higgins and other members of the Farm Bureau met with lawmakers including Sens. JD Vance, R-Ohio, and Sherrod Brown, D-Ohio.

They mentioned one priority as funding conservation programs that help farmers maintain healthy and productive land for their crops and animals—and the planet. They said climate change poses new challenge for farmers.

“They are sort of the front lines of climate, depending on which part of the country you’re from, especially. Way too much flooding in Midwest that there hasn’t been. The problems of algae blooms in the western basin of Lake Erie. That’s not the only reason, climate, but that’s contributed to it,” said Sen. Brown.

Extreme weather events like droughts have contributed to rising crop insurance costs, which the Congressional Budget Office predicts will go up 29% in the next decade.

Meanwhile, the Department of Agriculture predicts crop prices to decline overall through 2027.

“We’re going to see a decrease projected of 25% in farm income in 2024, so these things are important to keep the farms going for many generations to come,” Higgins said.

Ohio farmers called for stronger safety net measures, such as subsidies for crop yield and natural disaster insurance, as well as commodity support programs to maintain a price floor for certain crops.

“There really is this tension between how much do you spend on environmental priorities and how much do you spend on crop insurance?” said Sen. Vance. “I think there’s a Democratic and Republican divide there. I tend to agree with John Bozeman, the Republican chairman, that we should be more focused on crop insurance in the Farm Bill.”

The farm bill has traditionally been a bipartisan effort in Congress, but a partisan divide and the current state of the farm economy have slowed progress on a final bill.

Lawmakers have particularly clashed on whether or how to trim the next farm bill’s price tag.

The last farm bill was estimated to cost $867 billion over 10 years. About 77% of that went to Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP) benefits. The Congressional Budget Office projects the next farm bill will cost $1.51 trillion, with higher food prices driving an increase in SNAP spending.