Juneteenth — also known as Emancipation Day and Freedom Day — commemorates when the last enslaved African Americans learned they were free on June 19, 1865 in Galveston, Texas, where Union soldiers brought them the news two years after the Emancipation Proclamation.

The Hansparker Memorial event, which begins at noon on June 19 at the cemetery, aims to raise funds for a headstone to memorialize John and Emily Hansparker, who lived quietly on Front Street in Cuyahoga Falls for many years. The couple was buried together with Helen Hansparker, who is possibly the couple’s daughter.

The event will also inform residents about the city’s role as a vital component of the Underground Railroad, said Jeri Wilcox Holland, co-organizer of the event. Holland is also president of the Cuyahoga Falls Historical Society, although the event is not sponsored by the society.

“They need (to be) recognized,” she said. “It just started out I was reading letters from former enslaved people, and it just hit home. I can't understand how they survived. When they were emancipated, they had to start a whole new life that they knew nothing about and then they moved to Cuyahoga Falls right after they were freed. I just I don't know how they did it.”

Much of the original research to find out who the Hansparkers were was done through the historical society. But with public interest, it became a grassroots effort, said Shawn Andrews, Cuyahoga Falls Historical Society secretary. Andrews is assisting in the research and community advocate Sunny Matthews is also helping organize the memorial.

Holland first came across a photo of John Hansparker while doing research at Taylor Memorial Library in the Falls, she said. She was creating a downtown display about slavery and abolition, with part of it dedicated to former slaves who lived in Cuyahoga Falls.

Holland found a shoebox in storage at the historical society, which contained two bank bills signed by notorious abolitionist John Brown, who was born in Hudson, Ohio, and shepherded many slaves through northeast Ohio until he was hanged for treason.

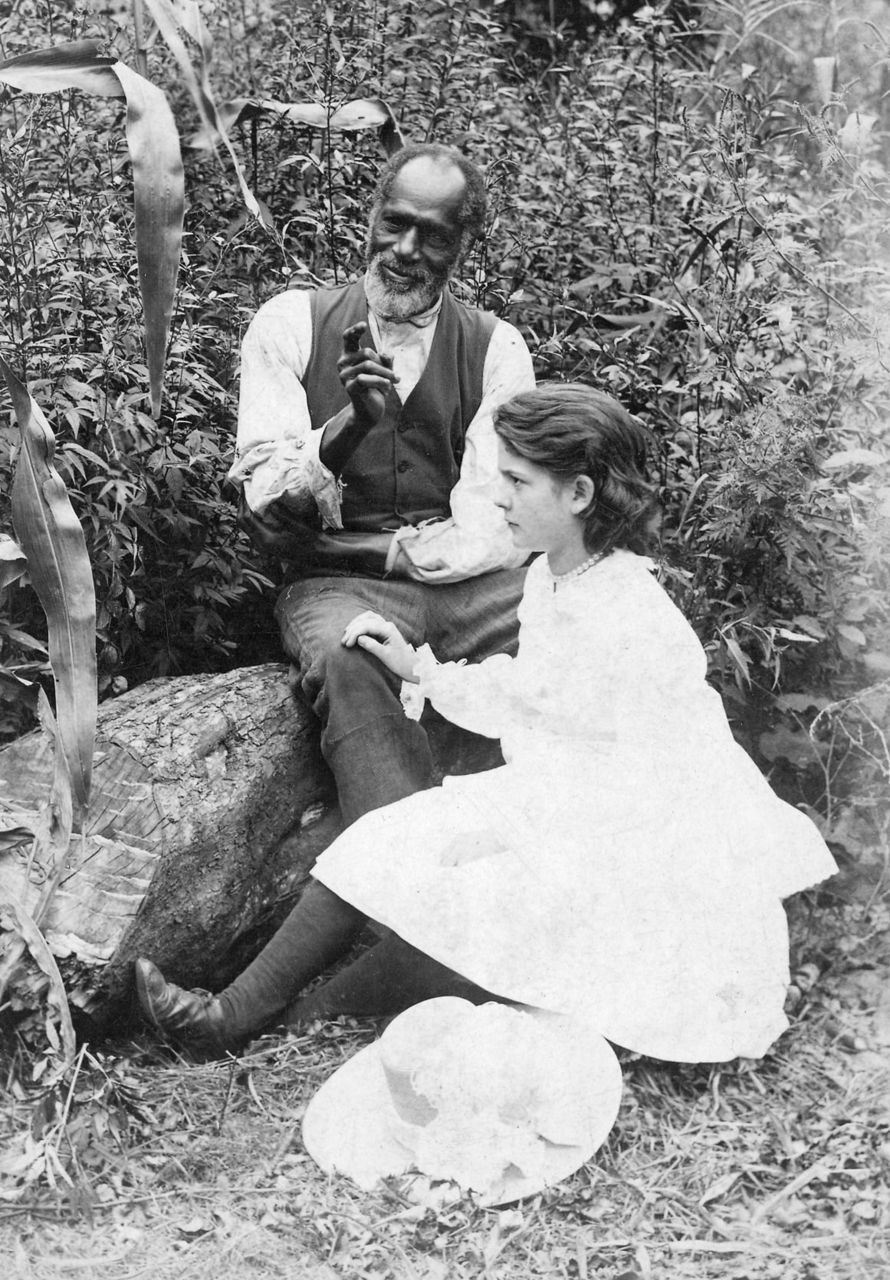

She also found a photo with writing on the back that indicated the subject was John Hansparker reading to a neighborhood child.

There are so few photos of Black residents in Cuyahoga Falls from that time period, so Holland asked Andrews — whom she calls the “cemetery guru” — to do more research.

Andrews found the Hansparkers in Oakwood Cemetery in Section B, an older part of the cemetery, but with no with death date for John Hansparker, she said.

Then, out of the blue, Andrews said she came across a second photo of Hansparker on Facebook.

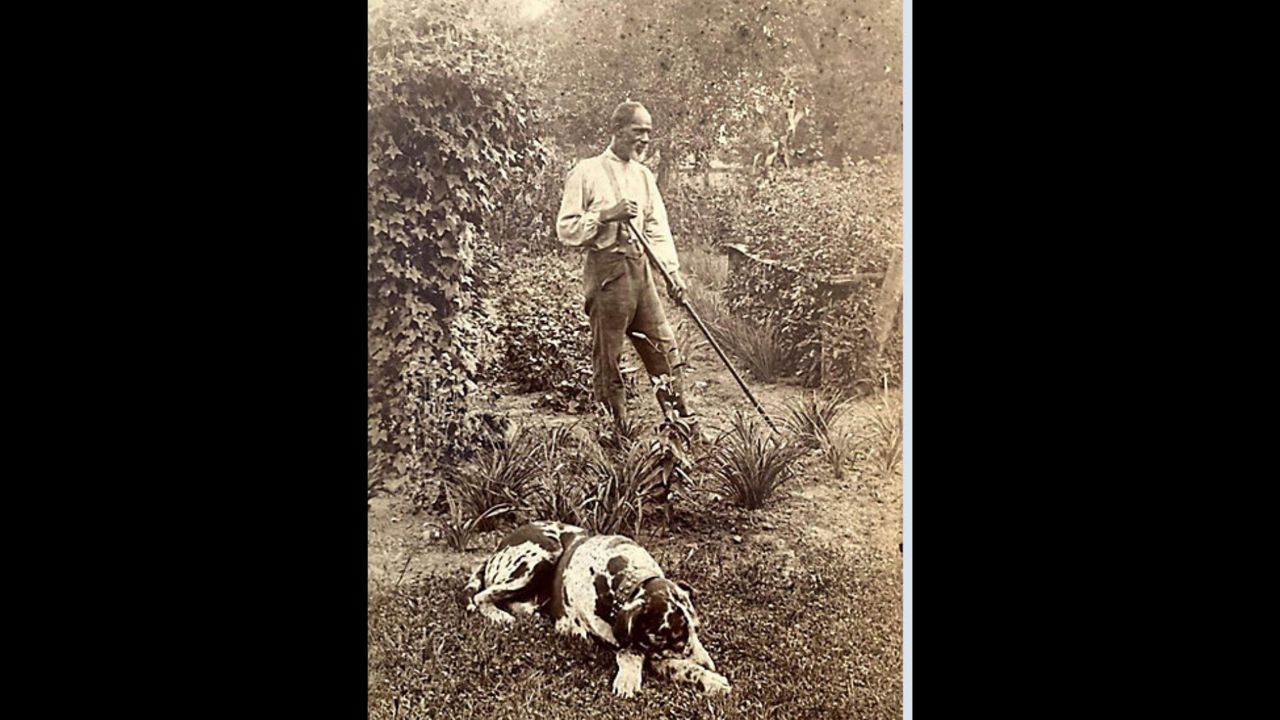

That photo was posted by Ken Clarke, who recently wrote the book “Wolves and Flax,” documenting the Cuyahoga Valley wilderness and the prominent Prior family, for whom John Hansparker later in his life served as groundskeeper, Andrews said.

The photos were taken by traveling salesman and photographer Laurel James, who was married to Malen "Minnie" Prior, the great granddaughter of Simeon Prior, Andrews said. The elder Prior founded Northampton Township.

“What makes it special is that [Hansparker] was an ordinary person but he happened to be photographed and documented in this area, and may have even escaped slavery. Certainly, his wife did,” Andrews said.

The historical society then republished the photo on its Facebook page, explaining the synchronicity that brought to their attention two rare photos of a former slave, which got people talking, Andrews said. The community wanted the family to have a headstone.

According to census records and other documents, John Hansparker was born in May 1836 in Virginia. When the Civil War ended in 1865, he traveled to Cuyahoga Falls, which was then a village. In 1866, he met Emeline Hopp, who was born in Missouri in July 1842. Known as Emily, she was biracial and also a freed slave.

The pair married on Nov. 19, 1867. After they married, they lived for a time with a barber named Gordon Meahan, a former slave from Virginia. Meahan was able to help out the newlyweds until they could support themselves.

Eventually, John Hansparker was employed at Falls Rivet Works and also worked as a groundskeeper and porter. Emily Hansparker took on work as a laundress.

Once the Hansparkers were on their feet, they moved into a little house at 325 S. Front St. near the Cuyahoga River, on a lot now covered by the Sheraton Riverfront Suites parking lot.

The couple had two children who did not survive childhood.

For their rest of their lives, the Hansparkers took in boarders, paying forward the assistance they received, to help other Black citizens who came to Akron and Cuyahoga Falls to start new lives.

During slavery, those enslaved were forbidden to learn to read and write. But once free, John Hansparker learned to read, which he enjoyed practicing with the neighborhood children, and they were fond of him, records indicated.

The Hansparkers continued working throughout their lives. John died before Emily who passed in September 1907, according to her death certificate. No certificate has been found for John, Holland said.

Research is ongoing to identify others who are buried without headstones in Oakwood Cemetery.

“I just think it’s time to start bringing some of these pieces to light that have been in the dark for some time,” Andrews said.

Being buried without a headstone is not uncommon, she said. In those days, it happened when the dead were very poor, or sometimes when they were the last surviving member of a family.

“Really, it’s a nice gesture to build this headstone to John Hansparker and serves as a memorial to other Black folks who came through Cuyahoga Falls escaping slavery,” Andrews said. “I feel like this marker is really for any of the folks that came through and are unmarked.”

Visit the Cuyahoga Falls Historical Society website for more information.

![Ohio Sen. Terry Johnson, R-McDermott, added into the state budget bill a provision allowing medical folks to refuse service if it violates his or her religious beliefs, according to Ohio Right for Life. [Joshua A. Bickel/Dispatch]](https://s7d2.scene7.com/is/image/TWCNews/donot_reuse_cdg_c2b746a7-48d4-475d-8809-70053ed78a34-cebcollinsl)