LOUISVILLE Ky. — Financial struggles have defined the past 18 months for the Americans hit hardest by the pandemic, from those who couldn’t afford to bury their loved ones to those who saw their businesses crumble. But many companies deemed “essential” early in the pandemic have a different story to tell.

Not only did the biggest essential businesses in Kentucky survive during the pandemic, but they also thrived. In the second part of a three-part series on life as an essential worker in Kentucky, Spectrum News 1 looks at how the pandemic benefited three major Kentucky employers — Amazon, Kroger and UPS — and how those benefits flowed mostly to executives at the top.

It’s hard to imagine a bigger winner during the pandemic than Amazon. The e-commerce giant hit $386 billion in sales last year, up more than $100 billion over 2019, as consumers shifted even more of their buying to online retailers.

Like many states, Kentucky is home to tens of thousands of Amazon employees who work at facilities from Hebron to Campbellsville.

Early in the pandemic, Amazon acted quickly to reward those workers for staying on the job while many Americans stayed home. In mid-March of 2020, the company temporarily added $2 to the hourly wages of what it called "our Amazon retail heroes." In June of 2020, it paid a $500 “Thank You" bonus, and those with the company at the end of the year received a $300 holiday bonus.

Chris C., who asked that his last name not be used, began working as a stower at a Louisville Amazon warehouse in January. “I was a later employee in the quote-unquote essential worker era,” he said.

But Chris did not miss out on the COVID-19 era. In fact, he began working at Amazon during the state's deadliest month of the pandemic, when COVID-19 was killing an average of 35 Kentuckians a day. Vaccines were only available for health care workers and the elderly, making it one of the riskiest times to work in a crowded warehouse. Chris said Amazon took safety seriously, but hazard pay and appreciation bonuses were in the past.

The orders, however, kept coming. As a stower, Chris was responsible for packing small boxes filled with products into larger containers that would go on a truck. “My feet would hurt bad. I’d come home with calluses,” he said. “But you'd still be expected to hit these absurd rates, around 320 packages an hour.”

A busy Amazon meant a higher Amazon stock price, which sent the net worth of founder Jeff Bezos soaring. Chris said he and his co-workers mostly joked about Bezos, reserving their ire for their immediate supervisors. Still, he can see why others might not be laughing.

“I can completely understand how people are very, very mad that Bezos almost doubled his wealth during the COVID-19 pandemic, while other people struggled to survive,” he said.

Bezos has indeed seen his net worth grow by nearly $100 billion since the start of 2020, according to Bloomberg’s Billionaires Index. In the past several months, he’s cashed some of it in, too, selling more than $6 billion worth of Amazon stock ahead of his July 5 retirement. Meanwhile, in all of 2020, Amazon spent $2.5 billion on bonuses and incentives for its more than one million global employees.

Amazon’s success during the pandemic helped buoy other companies, including United Parcel Service, Louisville’s largest employer.

In 2020, UPS recorded a record-breaking $84.6 billion in revenue, a 14% increase over 2019. The growth, like Amazon’s, was attributed to the pandemic-led e-commerce boom.

Unlike Amazon, though, UPS did not reward workers with bonuses or hazard pay tied to the pandemic, according to spokesperson Jim Mayer.

“We’ve offered bonuses off and on for years,” he wrote in an email. “We have not adjusted pay specifically as a result of the pandemic, but rather market conditions. If the flow of applications isn’t what we need it to be at a given time, we will enhance incentives."

The lack of hazard pay resulted in multiple petitions calling on the company to provide it. One, launched early in the pandemic, received nearly 300,000 signatures.

Despite not offering hazard pay, UPS did provide two weeks of paid sick leave for workers sick with COVID-19 or quarantining after exposure. It also thanked its drivers with tweets.

UPS had two top executives during the pandemic, and they were both rewarded handsomely. David Abney, who had been with the company for 46 years, retired on June 1 and received a $5.84 million compensation package for his five months at UPS in 2020. His replacement, Carol Tomé, pocketed $3.78 million, for a total of $9.6 million between the two executives in 2020.

While UPS and Amazon thrived last year because people stayed home, Kroger was the beneficiary of their rare trips out.

The country's largest supermarket chain, which employed more than 21,000 people in Kentucky as of 2018, saw sales jump to $132 billion, an 8.4% increase over the prior year.

Like Amazon, Kroger responded to the pandemic by instituting a period of hazard pay and a series of bonuses, including a $300 “appreciation bonus” in March of 2020 and a $400 “thank you bonus” in June of 2020.

Six months later, as cases surged, workers called for the return of hazard pay. “I guess we’re no longer considered heroes,” Mason Sims, who worked as a pharmacy technician at a Lexington Kroger last year, told Spectrum News 1 in January. The following month, Kroger gave front-line workers $100 in store credit and 1,000 fuel points. At the time, the company boasted of spending $1.5 billion on "COVID-related reward and safety measures."

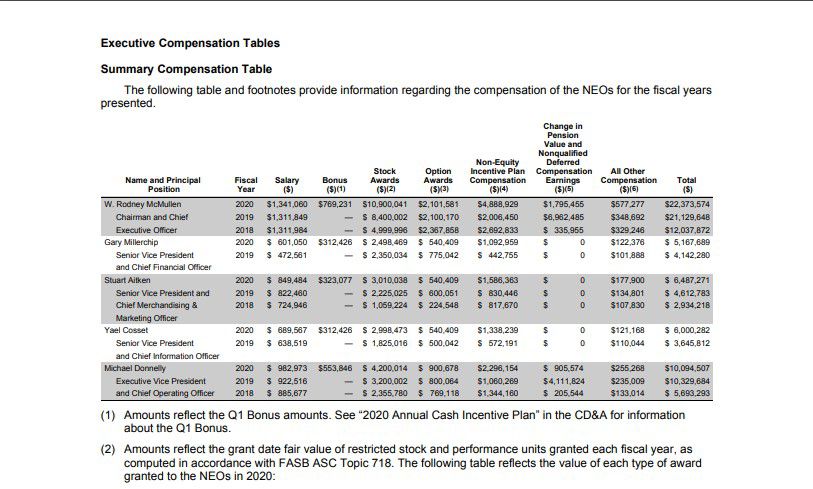

Sims and his co-workers never saw hazard pay renewed, but he did learn the company’s CEO, Rodney McMullen, raked in $22.4 million in compensation in 2020, a $1.2 million increase over 2019.

“I wasn’t surprised because it happens every year — the top gives themselves a raise and ours stays the same,” he said. “It’s not right." A Kroger spokesperson did not respond to a request for comment.

Sims said the slight from McMullen was especially insulting because the executive has roots in Kentucky. "He was a University of Kentucky student and he started out with Kroger," Sims said. "He loves to share the story about how he bagged groceries, worked in all these different departments and worked his way up to become CEO, but he forgot about all of us along the way."