LEXINGTON, Ky. — A few women in 1968 began demanding the right to apply for jockey licenses citing the Civil Rights Act of 1964, which banned discrimination in hiring based on race, religion, gender or national origin.

What You Need To Know

- Diane Crump rode in 96th Kentucky Derby in 1970

- She was the first female jockey to ride in the race

- She says she does not know why there are not more women jockeys

- Crump now sells horses at her Virginia farm

Called “jockettes” by members of the press, most of their applications were rejected by horse racing bureaucracy, which alleged women were unqualified to participate due to “physical limitations” and “emotional instability.” Female jockeys who attempted to ride were met with boycotts by male jockeys.

None of this fazed Diane Crump. She was just 20 years old in 1969 but had already proven she was a skilled rider during years of workout rides on difficult thoroughbreds.

“I basically got on all the horses that no one else wanted to ride,” she said. “I rode them well because I am the one who broke them.”

Granted a permit to ride at Florida’s Hialeah Racetrack, Crump, surrounded by a protective phalanx of police officers, walked calmly toward the saddling enclosure on Feb. 7, 1969, while tuning out the hecklers in the crowd.

“Diane Crump had a lot of firsts when it came to female jockeys and the right to ride,” said Jessica Whitehead, curator of collections at the Kentucky Derby Museum. “Not only was she the first woman to ride in a professional, pari-mutuel race in the United States in 1969, but her subsequent appearance in the Kentucky Derby only a year later, brought the female jockey controversy to unprecedented levels of national attention. Having a female jockey participate in such a prestigious race — without succumbing to the absurd kinds of mistakes or breakdowns male racetrackers had been trying to assert would happen to a woman under pressure — proved that women could ride just as well as the top male jockeys in the country. It opened the door for so many women who had been told ‘no’ their entire lives.”

Crump’s participation in the 96th Kentucky Derby on Saturday, May 2, 1970, made her the first female to do so in the race’s 95-year history and 1,055 entrants.

EARLY LIFE

Crump, 73, was born in 1948 in Milford, Connecticut, the daughter of Walter and Jean Crump. Crump had an early interest in horses, despite living in an area almost completely void of their presence.

“I lived in Connecticut until I was 12, and then we moved to Florida,” Crump said. “In Connecticut, there were zero horses.”

Crump began taking riding lessons in Florida when she was 13. She begged her parents and created a detailed plan, working odd jobs here and there to save money to help fund the purchase of her first pony.

“Becoming a jockey was not a surprise to me because I just love to ride, and I wanted to ride. That was my passion in my life,” she said. “When I was galloping horses and learning how to break horses out of the gate, I was like, ‘Why can’t I do this?’ I could work a horse three-quarters of a mile out of the gate with six or seven other horses in the gate. All of those were jockeys that were riding races and I could beat them in the morning, so why couldn’t I try in the afternoon?”

A year after buying her first horse, Crump got a job handling the weanlings on a thoroughbred farm. She said early on she didn’t even know it was a thoroughbred farm, she just knew it was a horse farm.

“The owners of the horse farm took me to see a race, and I was fascinated. I loved it,” she said. “Where I boarded my riding horse was only two miles from the track, and I’d ride down there all the time. We could stand outside the gate and watch the races around the fence because kids weren’t allowed if you’re under 16. The whole thing fascinated me. I learned how to break yearlings. I learned how to gallop on the farm. From there, I went to the racetrack, and I never looked back.”

LIFE AS A FEMALE JOCKEY

Crump said she was the lone female jockey riding in most of the races.

“There were a few other girls riding, but 99% of the races would have been all men,” she said. It’s still that way.”

Crump said she cannot pinpoint particular reasons there are not more women jockeys.

“I get asked that all the time, and I don’t know,” she said. “I don’t exactly understand it. I did think there would be more and obviously there are more coming. There are some good women jockeys out there, no doubt, but you know, the numbers remain low.”

If she had to speculate, Crump said she attributes the lack of women jockeys to the horse racing industry’s history of being slow to accept women in the role and women’s overall lack of interest in the occupation.

“I don’t ever remember as a kid ever seeing a woman on the backside,” she said. “A few years later, I’d see one or two, maybe a groomer or a pony rider, but I never saw a girl exercising horses. Now, I guarantee you women probably make up half of the backside help, but as far as becoming jockeys, I don’t know why more don’t. I just love racing, and I didn’t care about the rest of it.”

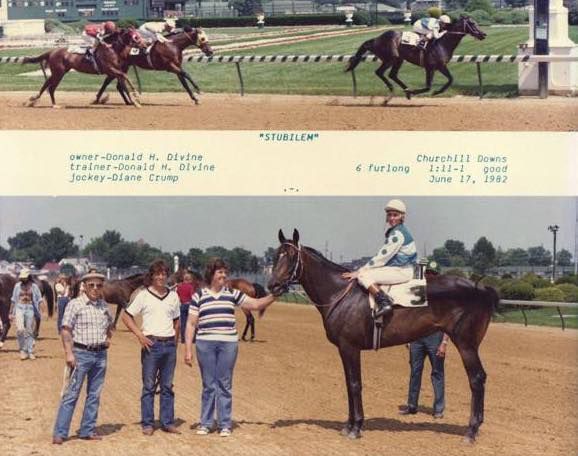

Crump was galloping horses at Churchill Downs for her then-husband and trainer, Don Divine, and the horses’ owner, George Brown, of Brown-Forman, noticed her.

“They would come in the morning to watch the horses work and go to the grandstand and watch them break out of the gate,” she said. “They got to know me a little bit, and they thought I would be a really good rider.”

It was in the fall of 1968 when attorney Kathy Kushner took the effort to get women permits to race horses to court. Kushner and a team of lawyers won the case.

“There was a lot of uproar about any woman that gets named on a horse getting boycotted,” Crump said. “The horse owners said they weren’t putting up with it and told me they thought I’d be a good racer. But, they owned part of Churchill Downs and to avoid any controversy, told me that when I got to Florida, they were behind me.”

After going to Florida and getting her license, the owners told her they wanted her to ride.

“Out of the clear blue sky, somebody named me on a horse,” she said. Nobody boycotted me—there had already been one boycott at Tropical Park against Barbara Jo Rubin. I was winning some of the races there with two-year-olds. I broke Fathom, and that’s the horse I rode in the Derby.”

Brown was getting older and knew he probably would never have another chance to see one of his horses run in the Derby, Crump said, adding that with today’s rules, Fathom would not have been eligible for the Derby because of the amount of money he had won.

“In that era, you didn’t have to have that, and it was his dream to run one horse in the Derby before he died,” she said. “He asked me if I would consider riding Fathom in the Derby. I said, ‘Of course.’”

Crump and Fathom finished 15th in the field on 17 that day.

“Did I have a chance? No, but it’s still a dream. Everybody dreams and sometimes things happen out of the ordinary. For me, my proudest feat was that I was the first woman that actually got to ride in that race, that I’m the one that didn’t get boycotted. I always felt so good about that, not really realizing the recognition I would get for being the first woman to ride in the Derby.”

Like many members of the first generation of female jockeys, Crump had to cope with extreme prejudice and resistance to her chosen career path.

“I think those kinds of obstacles instilled in them a strength of character and conviction that made them better riders, and better people,” Whitehead said. “One thing that has amazed me while researching the lives and hearing the experiences of these women is how their passion for fast horses, more than anything else, kept them focused in the face of the worst kinds of frustration. That passion made them great horsewomen and continues to inform their lives, even in retirement. Diane told us in an interview that her mother painted a mural on her childhood bedroom wall inspired by Walter Farley’s Black Stallion series, and it gave her a tangible reminder as she woke up and went to sleep that horses were what her future held. I think her legacy will be inspiring to other young women, who may feel uncomfortable about breaking into a still-male-dominated industry, not to take no as an answer in the face of true passion for horses.”

LIFE AFTER RACING

When Crump retired for a time in 1985, she worked at Calumet Farm in Lexington, and beginning in 1991, she worked as a trainer for a small stable of horses at the Middleburg Training Center in Virginia.

She resumed race riding in 1992 and rode races through 1998 before officially retiring from racing in 1999. She now runs an equine sales business in Virginia. A biography, “Diane Crump: A Horse Racing Pioneer’s Life in the Saddle” by Mark Shrager was published in 2020 by Lyons Press.