LOUISVILLE, Ky. — The timing of last week’s bomb threats targeting historically Black colleges and universities (HBCUs), including one in Kentucky, made sense to Lecia Brooks. The threats, which are now the subject of an FBI investigation, came on the first day of Black History Month and provided a reminder of how violent that history was.

“White supremacists have been using bomb threats and other violence against Black folks since Reconstruction, and it really saddens me that we’re intent on getting back to that,” said Brooks, the chief of staff and culture for the Southern Poverty Law Center.

The bomb threats last week were made to at least 17 HBCUs. Kentucky State University, one of two HBCUs in the commonwealth, was among them. The threats did not include any actual explosives, but the FBI said they are “being investigated as racially or ethnically motivated violent extremism and hate crimes.”

Brooks took it a step further. “These are acts of domestic terrorism because they are meant to invoke fear, not only in the targeted victim or institution, but in the larger society,” she said.

The targeted institution is often a seat of Black prosperity, or independence, Brooks said. She suggested HBCUs may have been threatened because white supremacists are attempting to stamp out Black political power in one of the places where it forms. “I think greater attention has been brought to HBCUs because of our vice president,” she said, referring to Kamala Harris, who graduated from Howard University, a HBCU in Washington, D.C.

Terrorizing Black Americans with bombs and bomb threats became increasingly common during the Civil Rights era and reached its peak in Birmingham, which was dubbed “Bombingham” because of the number of explosions and threats that happened there.

The bombing of the Sixteenth Street Baptist Church in 1963, which killed four young girls, may be the most well-known use of this form of political terrorism, but there are many other examples, including here in Kentucky.

One such attack took place in 1954, not long after Andrew and Charlotte Wade moved to Shively, a small city in western Jefferson County. Shively was a whites-only suburb of Louisville and the Wades could only move in after white friends, Carl and Anne Braden, bought the home and transferred its deed.

The Wades were quickly terrorized in their new home. Within days of their arrival, people burned a cross on their front yard and six weeks later, a bomb was set off under their daughter’s bedroom. The perpetrators of the crime were never arrested, but it had its desired effect — the Wades left Shively.

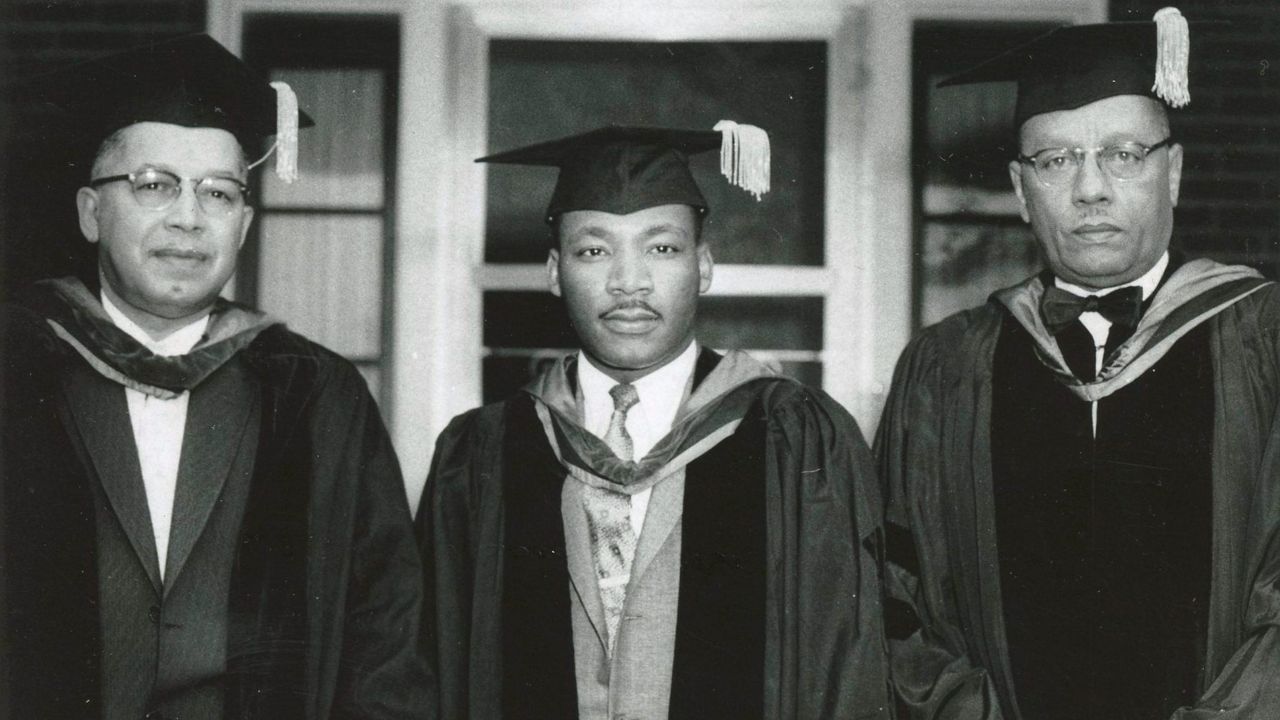

Often, the threat of bombings came without the follow through. In 1967, when Martin Luther King Jr. came to the Kentucky Derby to lead marches against housing discrimination, bomb threats were made against the Civil Rights icon, according to Tracy E. K’Meyer’s book Civil Rights in the Gateway to the south. Despite the threats, “the worst incidents involved college students drinking beer in the infield, a Derby tradition,” she wrote.

A year later, the Louisville church that King’s brother led was not as lucky. For several years in the mid-60s, the Rev. A.D. King preached at Zion Baptist Church in West Louisville. In the summer of 1968, he was in Memphis when a bomb went off at the church, damaging the building, but resulting in no injuries, according to a report in Jet magazine. “It is evident that the vicious seeds of racism are very much prevalent in the community,” he said at the time.

Lexington also has a history of racists using bombs as a tool of intimidation. In 1930, two Black families in the city saw their homes bombed as a part of a campaign to get them to move out of a mostly white area.

Decades later, a Black-owned drugstore in the city was bombed by members of the Ku Klux Klan, trapping owner Zirl Palmer, his wife, and his daughter under falling debris. Palmer was a pioneering Lexington pharmacist who, years after the 1968 bombing, told the University of Kentucky that the attack left him living in fear.

“It’s a very, very frustrating thing to be afraid to go to bed, afraid to get up, afraid to start your car, afraid of everybody you see that they’re going to knock you out,” he said.

Instilling fear, along with harming the people and property targeted, was often a goal of those carrying out these attacks.

“They would do anything they could to try to terrorize, or frighten Black folks back into some kind of submissive state,” Brooks said. “They attacked them at churches. They attack activist leaders’ homes. They thought it would bring Black people back in line. But it didn’t work. And it won’t work.”