LOUISVILLE, Ky — In June of 2019, nine months before Breonna Taylor was killed, and a year before protesters took to the streets demanding justice in her name, Louisville Metro Government launched the Synergy Project, an effort to address “challenges when it comes to police and community relations,” Mayor Greg Fischer said at the time.

Two years later, those challenges have grown and Fischer is seeking more than half a million dollars to awaken the program from a pandemic-induced slumber. But some local leaders say Synergy is not designed for a post 2020-world and they’re pushing Metro Council to redirect funds toward efforts they said would better accomplish the same goal.

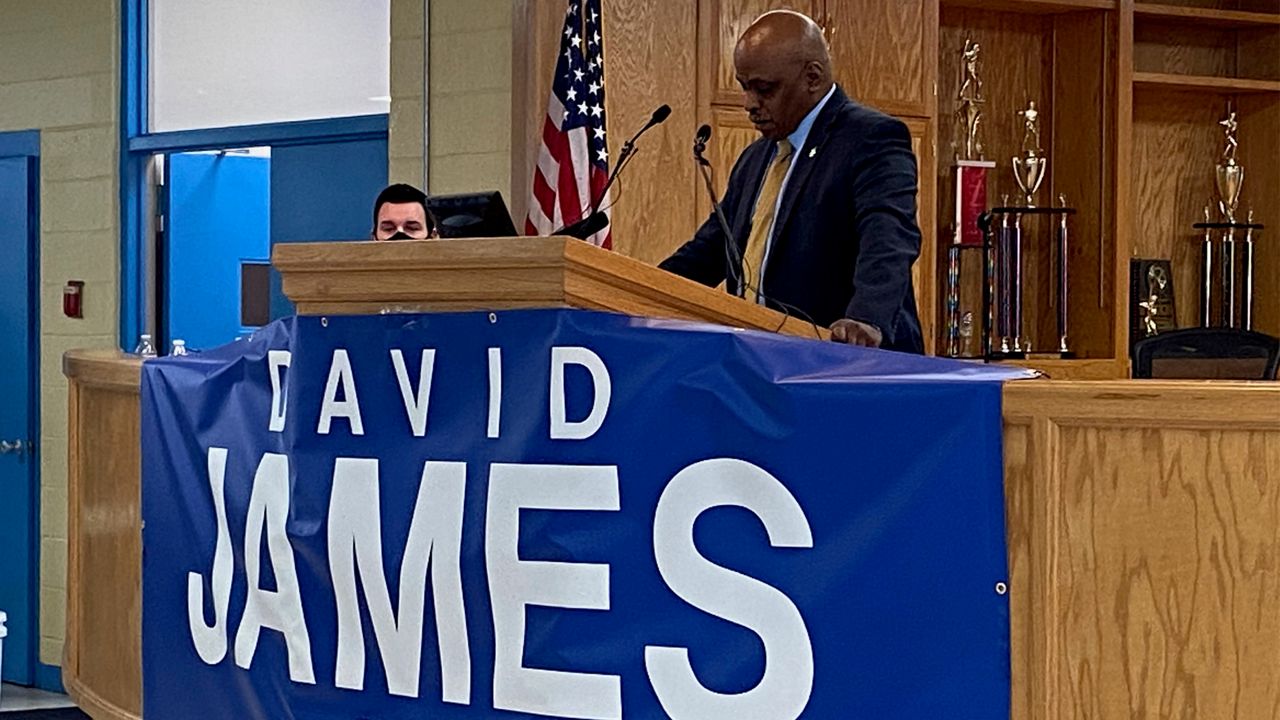

“I attended several Synergy meetings...and they were less than adequate,” Metro Council President David James said at a budget hearing last month. “They were horrible, quite frankly.”

James is among those supporting a change in the way the city builds trust between police and community members. The push for an alternative to Synergy is led by CLOUT, a local group of religious congregations “working together to solve critical community problems.”

Leaders at CLOUT are calling for a “truth and transformation” process run by outside experts and designed to more forcefully confront what Rev. Reginald Barnes calls Louisville Metro Police Department’s history of harm.

“It's really a public acknowledgment by the police of the harm they have done over the years as an institution or perhaps a department, or even as individual police officers,” Barnes said. “They then commit themselves to improving that.”

The Synergy Project is based on the idea that bringing police officers and community members together for honest conversations will build trust between the groups and eventually, lead to broader societal change.

Upon its launch in 2019, Fischer said these conversations would allow “our community to really delve into complex issues and find solutions." But less than a year after those conversations began, the pandemic shut them down. In the same month, Taylor was killed in a botched LMPD drug raid. Months later, Louisville became a hub of the nation’s racial justice movement.

Those events make Synergy’s mission more relevant than ever, said Kendall Boyd, Chief Equity Officer for Louisville Metro Government.

“What we saw born out of those x-factors was more distrust between the public and LMPD and an inability to effectively communicate because we still technically live in a virtual world,” he said.

In the time since the program launched, LMPD has also been declared a “department in crisis” after a top-to-bottom review by Hillard Heintze, a Chicago-based security consulting company. Among the firm’s recommendations: LMPD should reimagine the way it works with the public, elevating the community to a “equal partner in helping influence and direct public safety strategies, policies, practices and priorities.”

Synergy’s supporters and critics say that opening the lines of communications between LMPD and the community is a vital step in achieving that. How it's done is where they differ.

In practice, Synergy and the “truth and transformation" process are not dramatically different. Both are meant to bring very different people to the same table to discuss things they likely disagree on.

At Synergy meetings held prior to the pandemic, this meant people who had been “arrested by police officers sitting in the same circle with the officer that may have arrested them,” Boyd said.

Participants would go around the table and talk about their feelings toward the police or their feelings about being an officer. “It may be offensive, may be out of anger, sadness, frustration, whatever — but they get to say what is on their heart,” Boyd said. Then, someone else would have chance to talk. They may say “the polar opposite, but at the same time, we're having dialogue,” Boyd said.

Barnes, who was able to attend several Synergy meetings in 2019, said those dialogues weren’t worth much.

“They just really weren't going into any in-depth conversations and that's not going to lead to significant change,” he said. “I don't think it was really designed to go in depth.”

James took his criticism further. "Synergy was designed and set up so that there could be only shallow conversations," he said.

Barnes argued that the “truth and transformation” process would be different in several key ways. For starters, it would not be run by Metro Government, but by the National Network for Safe Communities (NNSC). It would also begin with the acknowledgment of harm by police.

“That's an important step they’re leaving out,” Barnes said of Synergy. “Particularly for the Black community, if you want to build trust, that acknowledgment has to happen.”

Boyd is skeptical of that approach. He said it can already be a challenge to get police to participate in these sessions. “If LMPD has to come in and say, ‘We acknowledge harm,’ that's putting them on the defensive,” he said. “There are a lot of great police officers that say, 'I've never shot anybody. I've never killed anybody. I don't harbor any racist animus towards anybody.'"

For its part, the union for LMPD officers does not take a stance on the continuation of Synergy, River City FOP press secretary Dave Mutchler wrote in an email. He did say that that the union supports the project’s mission. “It can often be useful or helpful when citizens have an opportunity to talk and interact with police officers outside the scope of their normal law enforcement duties,” he wrote.

For now, the future of Synergy is in the hands of Metro Council, which will vote on a final budget later this month.