LOUISVILLE, Ky. — School in Kentucky is finally back in session. More than a year after K-12 schools in the state shut down due to the emerging threat of the coronavirus, each of Kentucky’s 172 public school districts will all be required to offer in-person instruction by the end of March.

The journey from March 2020 to March 2021 has seen parents, teachers, and students face unprecedented challenges amid a worldwide pandemic, presenting opportunities and obstacles that will likely shape the future of education for years to come.

A year after the arrival of COVID-19 in Kentucky, Spectrum News 1 is looking back at how the pandemic affected education:

Several days after Kentucky’s first COVID-19 case was identified in Harrison County on Jan. 6, the local school district told kids to stay home. Teachers were asked to implement NTI, or non-traditional instruction, allowing students to continue their studies while away. They were also tasked with giving their classrooms a deep cleaning.

“We're just going through cleaning all our tables, desks, pencil sharpeners, doors,” Stacy Lemons, an eighth-grade teacher at Harrison County Middle School, said at the time. “I've cleaned my filing cabinets, anything my kids would have been in and out of.”

Less than a week later, every student and teacher in Kentucky would be experiencing something similar. On March 12, Gov. Andy Beshear recommended that all school districts in the state stop in-person classes for at least two weeks.

“It is a big but necessary step,” Beshear said. He explained that keeping kids at home would give teachers, parents, and administrators time to prepare for a return to school in April. But for most, that return never came.

Jefferson County Public Schools (JCPS), the largest district in the state, released a plan for NTI in late March. Challenges emerged immediately in a district of nearly 100,000 students, many of whom lack the resources to learn at home. JCPS worked to deliver 25,000 Chromebooks to families that needed them and would eventually ramp up technology efforts, passing out hotspots to families that also lacked reliable home internet access.

This wasn’t just a problem in Kentucky’s urban areas. One analysis of the state, from the nonprofit Common Sense Media, said 241,000 Kentucky students, or 36% of the state's K-12 enrollment, was without adequate internet connection for remote learning. The Kentucky Department of Education (KDE) recommended that students in these households sit in a parked car in their school’s parking lot to take advantage of the wifi.

NTI presented problems for those students with reliable internet connections, too, said Dr. Jennifer Bay-Williams, a professor at the University of Louisville College of Education and Human Development. Some, like her high school student son, missed out on interventions they’d get in the classroom. Others missed out on the hands-on experiences that are so vital to early learners.

“With young children in particular, hands-on experience really matters," she said. "Being able to talk to peers really matters. That was definitely a major challenge for children's learning during COVID."

In early August, COVID-19 in Kentucky was at an all-time high. The seven-day average case count had crept above 600 and, with the new school year on the horizon, Beshear made a request of the state’s public and private schools — keep the kids at home.

"In my very core, I want us to get back to in-person instruction, but to ask our kids to go in with all our teachers and faculty at a time when it's not safe, it's something that we can't ask of them, and I'm not willing to," he said at the time.

The news was not amicably greeted throughout Kentucky, nor was it universally followed. Green County in central Kentucky was the first in the state to open to in-person instruction in mid-August. Within a week, it had returned to remote instruction.

As late summer turned into fall, Kentucky’s case counts continued to rise. But so did frustration from parents desperate to get their kids back in school. At rallies in Lexington and Louisville, groups calling themselves “Let Them Learn” demanded a return to the classroom.

Alyson Cleyman, a mother of a third-grader and sixth-grader in JCPS, said she was concerned about the amount of time her daughters were spending in front of a computer screen. "We're taking back the control at least for one day to make a point that our children should not be in front of screens for that amount of time,” she said. “It's really bad for their health.”

Separately, experts raised concerns about children missing out on the health and safety screenings that often take place in schools. For example, children did not undergo vision screenings that public schools typically conduct and child welfare experts said they worried child abuse was going undetected without teachers observing students in person.

As the fall semester wore on, more schools opened as more cases of COVID-19 emerged in Kentucky. The breaking point came on Nov. 18, when Beshear ordered all schools in the state closed through the end of the year.

“I don’t take this lightly. I know this will cause some more harm out there,” he said. “We cannot continue to let this third wave devastate our families.”

A month after that bad news, came some good news. The first Kentuckians were vaccinated against COVID-19 on Dec. 14. In January, Beshear announced plans to vaccinate teachers in hopes of reopening schools by March.

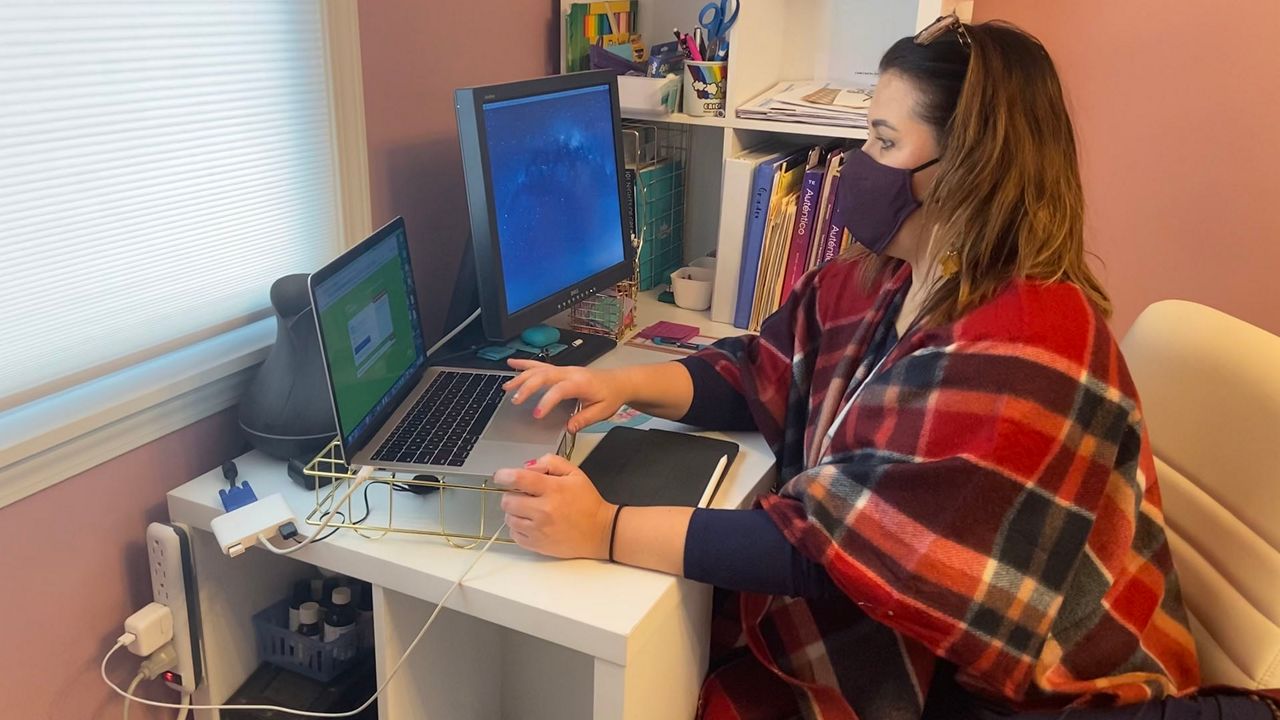

Erica Grossberg, a Spanish teacher in Louisville, told Spectrum News 1 that she was eager to return to the classroom. “I hate virtual,” she said. “It is all of the really hard parts of teaching and none of the good, rewarding parts.”

As the debate raged over when to open schools in Kentucky, some parents raised concerns about students falling behind. But Bay-Williams cautioned against viewing the past year through this lens. “They’re not behind,” she said. “They’re just at a different place in their learning.”

She said thinking of students being "behind" could lead to a destructive impulse to catch up. “The last thing we need is for kids to feel like they really need to catch up, to speed things up,” she said. “That's just going to be devastating. Students need opportunities to make sense of ideas. You can't hurry the building of important relationships and understanding.”

Soon all Kentucky students will have the chance to spend at least some of their educational time in the classroom. With a vaccine for children poised to be approved by this summer, the 2021-2022 school year could begin to look like pre-pandemic times.

But there are useful lessons to be taken from last year. One is the broad acknowledgment that technology and reliable internet connections are a key part of modern-day learning. According to the KDE, districts in Jefferson, Kenton, and Lincoln County increased the percentage of their students with internet access from 90% to approximately 95%.

With that internet access has come many new ways for teachers and parents to interact. Bay-Williams envisions a future where teachers easily share video clips of students with their parents to show how their kids are learning new concepts. She said parental involvement could improve, too.

“In Jefferson County, where you don't necessarily go to your nearby school, there's an access issue in terms of family engagement,” she said. ”I think we have an opportunity to really use technology as a way to interface with families — virtual math nights, for example. There are so many things we could do.”

She also said teachers have shown creativity with technology that will continue well into the future. “Teacher knowledge and use of technology has just exploded,” she said. “I am just amazed.”