LEXINGTON, Ky. – It was 30 years ago when a young, Black poet and visual artist from Danville was struggling with the definition of Appalachian he looked up in the dictionary. That struggle led to his not only creating a word but also a movement.

What You Need To Know

- Affrilachia coined by Frank X Walker, Kentucky's first Black Poet Laureate

- Oldest Predominantly Black writing group in America

- Goal is defining identity of Black poets and writers in Appalachia

- Group has published several books

A poetry reading in 1991 called “The Best of Appalachian Writing” in Lexington featured four authors from the Bluegrass State and poet Nikky Finney, from South Carolina. Finney, who is Black, was the sole voice of color in the lineup.

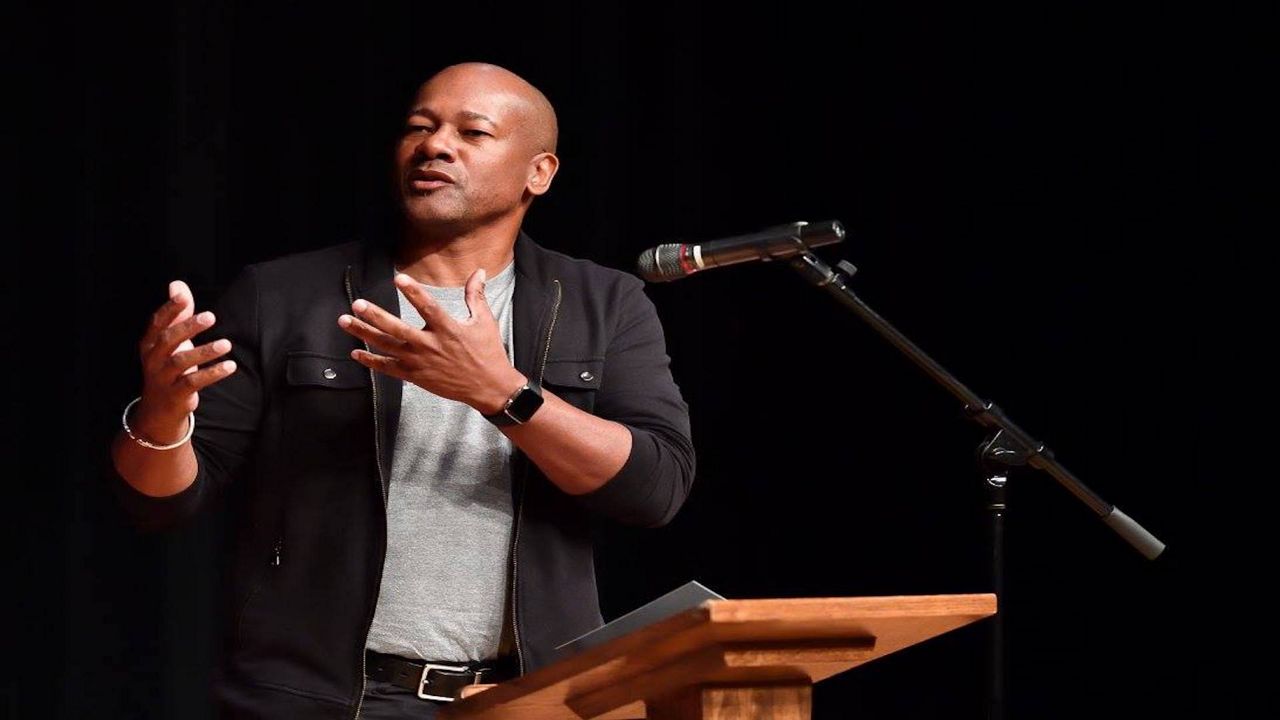

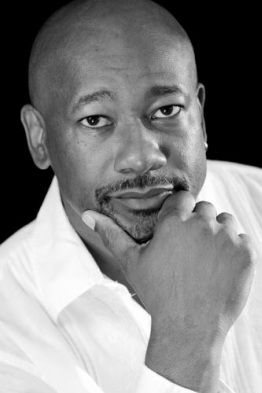

Frank X Walker, then a budding poet and an experienced playwright and visual artist, knew Black writers from Kentucky should have been represented. His disappointment led him to a Webster’s Dictionary definition of Appalachian that mentioned “white residents from the mountains.”

“I looked up ‘Appalachian’ and it said, ‘White residents of the mountainous region known as Appalachia,’” said Walker, Kentucky’s first Black Poet Laureate and a professor at the University of Kentucky. “I was struck by it being defined so exclusively and suddenly, the question I had to deal with was, ‘What are you if you're not white and you live in the same space?”

Walker began writing a poem that ultimately led to his coining the word “Affrilachia,” which he says signifies the importance of the presence of Black people in Appalachia and speaks to the union of Appalachian identity and the region’s Black culture and history.

“Part of what I do in my process to try to figure out things on the page – I think a lot of my work happens because I don't have a therapist – so I trust the page the way a person would trust the therapist,” he said. “So I sat down to tease this out and I'm writing about everything I know about Appalachia, and the people of Appalachia, and my people, and there’s more in common than different, so that's what the poem became about. At the very end of the poem, I wrote the lines, ‘Imagine being an Affrilachian poet,’ and didn't think much about it, but it made sense to me at that moment.”

Walker took the poem to a meeting of his writing group the next day and the consensus among its members was the word Affrilachian “opened up a new space” and since that day the collective has been known as the Affrilachian Poets.

“That word immediately was about allowing people who were in the space to feel like they were part of the space after having been defined out of it,” he said. “Our group was about trying to be heard, trying to gather people who felt marginalized, and trying to find good excuses to feel good about being in Kentucky and being pro-Kentucky.”

The group has grown to include 34 poets and authors ranging in age from their 20s to their 60s and in 2021 is celebrating 30 years of writing together while maintaining its goals of defying the persistent stereotype of a racially homogenized rural region and revealing relationships that link identity to familial roots, socio-economic stratification and cultural influence, and an inherent connection to the land.

When the group began with the University of Kentucky’s Martin Luther King Jr. Cultural Center as its spiritual home and Walker’s role as program coordinator, it became a popular hangout on campus for the student body and the poets. In the center’s back room that was part library, part study space, part escape from the outside world, the poets shared new creations. A nearby elevator was also utilized, with the writers gathering in the cramped space, turning off the power, and sharing their latest works. Finney, then a new English faculty hire at UK, was welcomed to the fold. In addition to Walker and Finney, founding members included Kelly Norman Ellis, Crystal Wilkinson, Gerald Coleman, Ricardo Nazario-Colon, Mitchell L. H. Douglas, Daundra Scisney-Givens, and Thomas Aaron. They were soon joined by Paul Taylor, Bernard Clay, Shana Smith, and Miysan T. Crosswhite.

“Over 30 years, of course, people graduated and left UK and went their separate ways,” Walker said. “But everybody stayed in touch because we have grown into a pretty close-knit family. And almost all those founders, and we laugh about this, either stayed in education or ended up running churches.”

Becoming a member of the group, which includes men and women of all races, is accomplished by invite only.

“Most of the new members are offered membership because they were either our students at the University of Kentucky, we met them on the road somewhere at another event in West Virginia or the Carolinas, or somebody we know sent them to us to visit and we vetted them. I think that's why it's still so small but it's also why we've remained so close. As a collective, I think everybody is a committed writer-slash-educator and we all have our own voices. But the places where we overlap are probably family, identity, place, social justice, and history. And within that, we still have our own voice.”

Walker said the group received a lot of attention in 2016 when it rejected the Governor’s Awards in the Arts recognition by former Kentucky’s former Republican Gov. Matt Bevin.

“We turned down the award because we didn’t agree with his politics and positions on all those things that we felt were important to us and we were writing about and championing,” Walker said. “He was not so supportive of those things.”

Many books containing compilations of work by members of Affrilachian Poets have been published over the years and workshops routinely take place. As the group has grown and evolved – it is now the oldest continually running predominantly African-American writing group in the country – its purpose has remained unchanged.

“We just wanted to have our voices heard, to find our voices to tell stories we thought were important and eventually became a little more organized,” Walker said. “We realized what we could do or stand for as a collective is to challenge this idea of what of who and what Appalachia was. That's been one of my joys, doing research about the region and talking about it. I give lectures all the time about Appalachians’ gift to African-American history and this is a little-known history that's so important. People never connected the two spaces.”

Walker gave some examples.

“The father of funk is considered George Clinton. The mother of the blues is Bessie Smith. The father of the blues is W.C. Handy. Nina Simone has no equal and throw in August Wilson for his theater contributions,” Walker said. “Booker T. Washington and the father of African-American history, Carter G. Woodson, are from Appalachia. But whenever you read their bios or people talk about them, they never talk about them being from Appalachia. Jesse Owens is part of that group, as are famous poets like Nikki Giovanni and Sonia Sanchez and activists like Angela Davis. There’s a whole pantheon of African-American superstars that get left out of the conversation when people are talking about Appalachia. It's always seemed like it was more comfortable to fall back on or revert to the negative stereotypes and caricatures of the region.”

Walker said one focus of Affrilachian Poets is challenging people’s definition of Appalachia so they take a second look and possibly be able to describe it in an inclusive way, such as how the foundation of Negro League baseball has its roots in Appalachian coal-mining camps.

“Those things have been bragged about, those individuals have been bragged about, but nowhere in a single text have they ever been discussed,” Walker said. “When people hear us talk about our love for the region and our contribution to it, and the ideas we champion that come from out of this space, people walk away almost always saying, ‘I didn't know that. Nobody's teaching that.’ I know for a fact that today's Appalachian Studies curricula at universities and community colleges across the region now teach in a more diverse way. There are writers, artists, and historical figures that get a lot of attention that before the Affrilachian Poets got zero attention as being connected to the region, so we feel like we help make that happen.”

Walker said because of the COVID-19 pandemic, he is unsure how the group will commemorate its 30th anniversary, but said he is sure they will find a way to celebrate it “in a big way.”

To learn more about Black history in Kentucky, visit our special Black History Month section.