LEXINGTON, Ky. – A public art project in Lexington continues to earn recognition nearly two years after its installation. “I Was Here” recently received an international award from Collaboration of Design Plus Art (CODAWorx), a creative online platform that connects artists, designers, and fabricators with municipalities and developers.

What You Need To Know

- Project began in 2016

- Unveiled in 2018 in downtown Lexington

- Spirit portraits act as on-the-street museum

- Donations sought to expand to other cities

A collaborative team created “I Was Here” for $50,000, well below the typical cost for projects given awards by CODA.

“Most of the projects submitted to the CODA awards are in the $200,000 to $1 million range, so, yes, it was a very small budget,” said Toni Sikes, CEO of CODAWorx. “To be quite honest, we don't normally have a budget category, but our partner in this project is Interior Design magazine, which is the leading design publication in the country, and they came back to us and they said, ‘We love this project. Can we create a special category to give them an award?’ So, we did. I love the project; I'm kind of floored by it.

It was so good and had such an impact on whoever was judging this they created a special category to make sure it got recognized. And since it's gone national due to winning the CODA awards, there are other places that want to bring it to their city, which is a special thing for Lexington as well.”

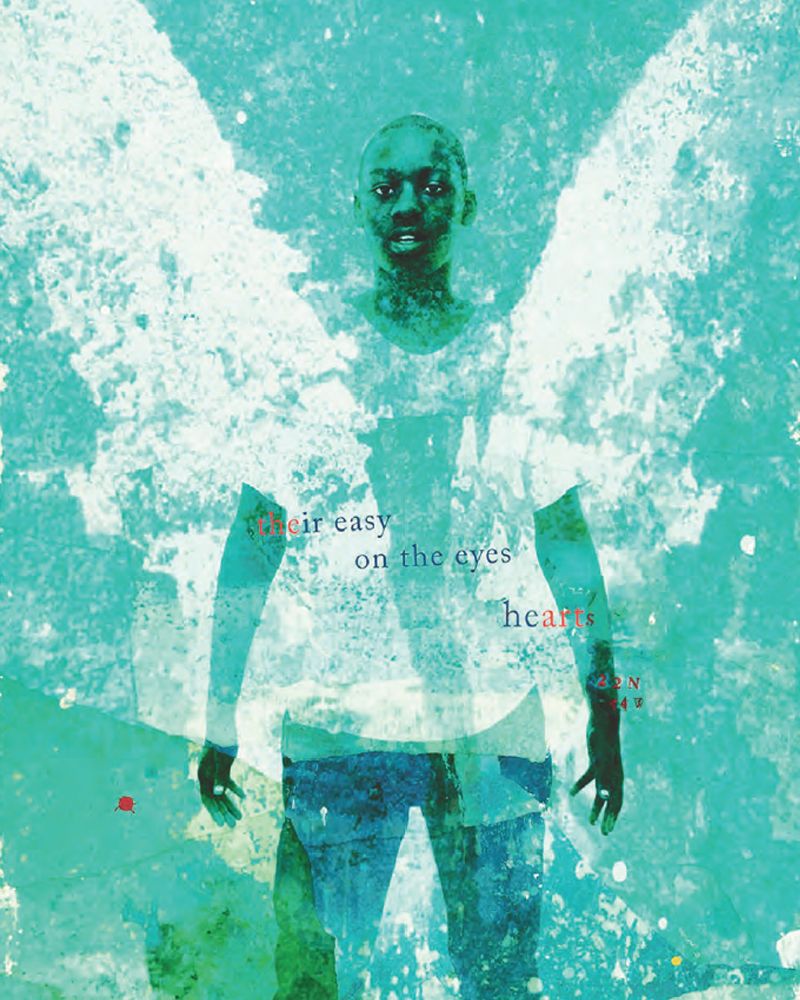

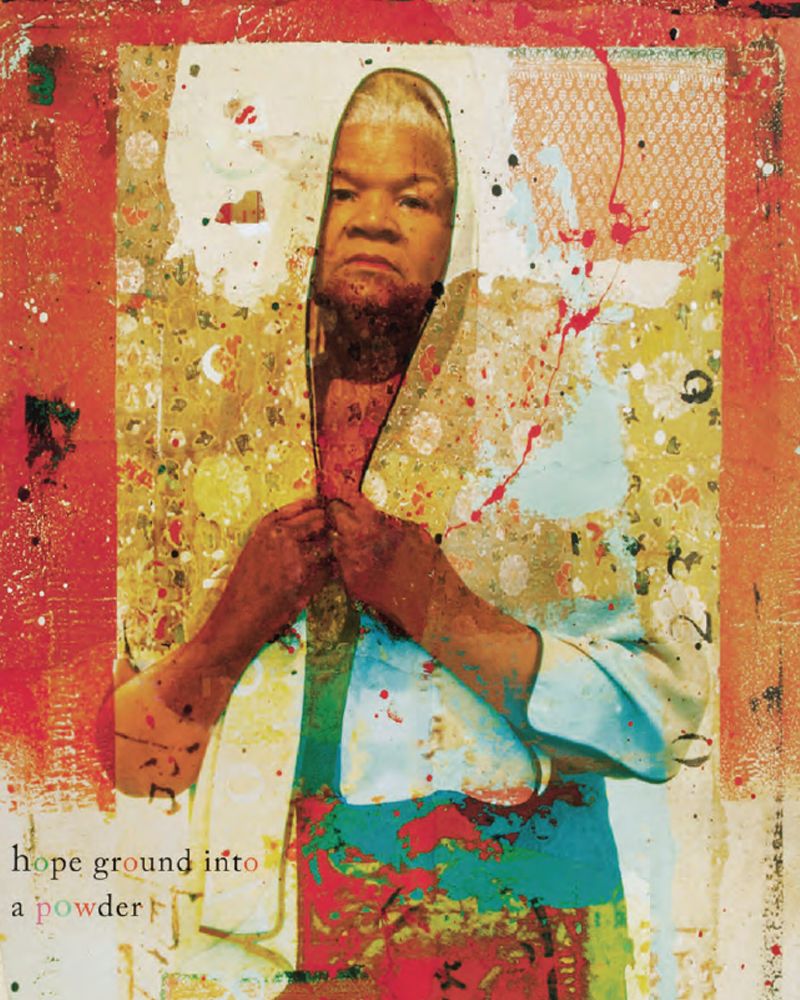

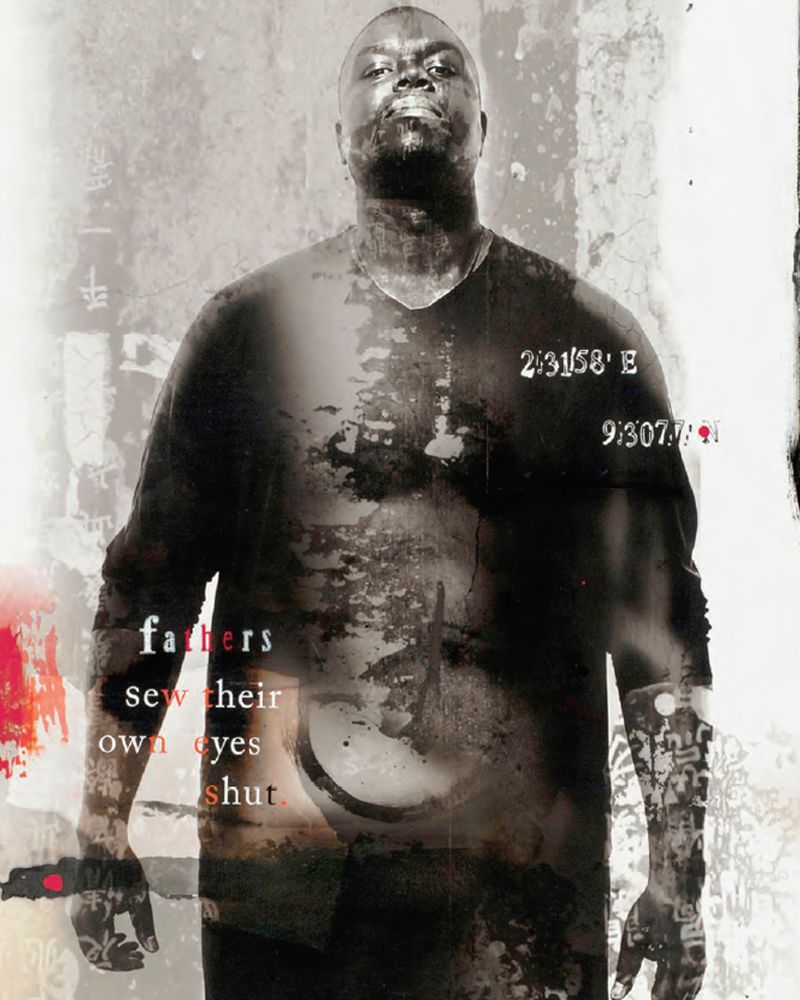

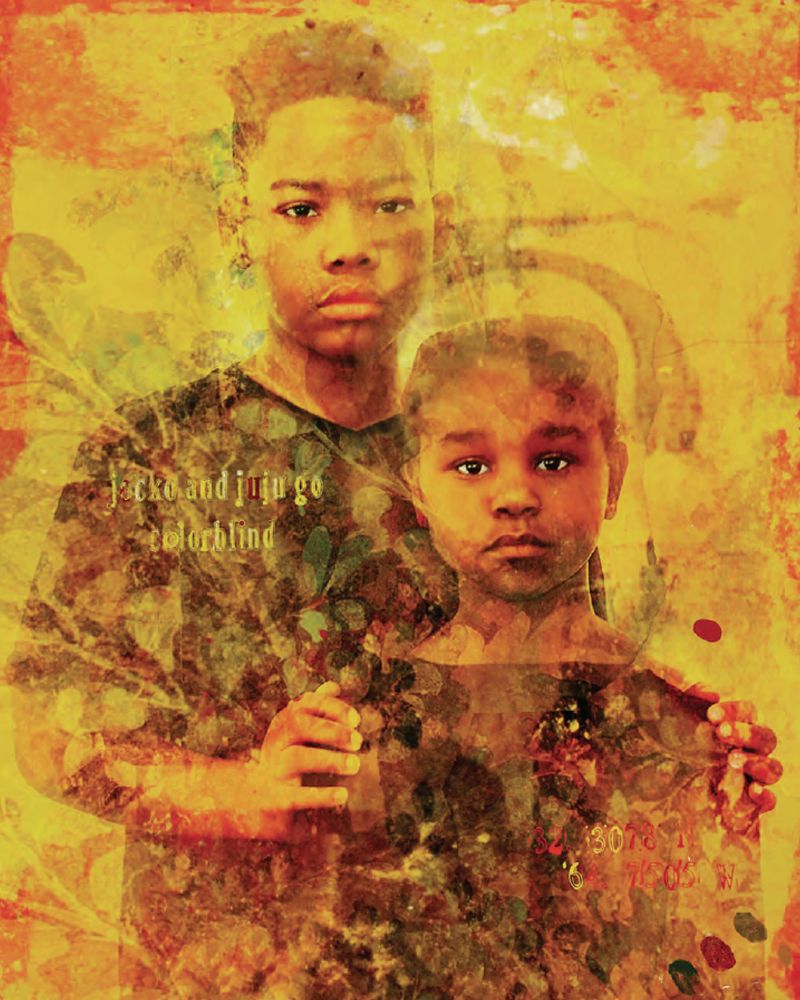

“I Was Here” features images of contemporary Black men, women, and children recreated as ancestor spirit portraits. A series of installations of these portraits transform historic sites significant to enslavement into on-the-street museums designed to educate and unify communities while creating memorials in public spaces.

Through the use of latitude and longitude, the project references locations central to the long life of the transatlantic Middle Passage slave trade. Through partnerships with historians, portraits of ancestor spirits on Roman blinds have been installed at historic locations with a possibly unknown significance and in the windows of businesses as a tribute to enslaved persons.

The project has been collaborative from the start. Beginning as a conversation about how to shift the spirit of the country in 2016, it took form initially as an artistic collaboration among artist Marjorie Guyon, photographer Patrick Mitchell and poet Nikky Finney.

“This is place-based engagement with the past that has altered the landscape so that the public quite literally sees familiar sites in new ways,” Guyon said. “The project brings art into the public square to instill a deeper understanding of our common humanity and stimulate a conversation about who we were, who we are and who we could be. ‘I Was Here’ takes the humanities out of the museum, university and gallery to give citizens the opportunity to come face-to-face with a visual history lesson rarely, if ever, encountered on the avenues of America.”

Guyon said the mission of the project is twofold: To create a visual testament of those who were sold into slavery and to instill a deeper understanding of our common humanity and create a means to “see the world with different eyes.”

“I’m not surprised ‘I Was Here’ is getting so much attention on a national level because the team has done a wonderful job promoting this project,” Mitchell said. “‘I Was Here’ has tapped into the spirits and they are taking it where it needs to go. It has had some obstacles, but when one door closes, another one opens. I don’t see how it can’t get to other places across the country.”

“I Was Here” Ancestor Spirit Portraits are displayed in the windows of downtown Lexington shops, bars, the courthouse, professional offices, studio spaces and the public library, among other places.

“The enslavement of Africans touched almost every corner of the United States but that history is largely hidden,” said Barry Burton, “I Was Here” project manager. “The project brings the past into view calling upon us to craft a vision for the future. The images, reproduced on translucent tapestries, allow light to pass through. They are clearly visible on both sides creating a visual metaphor for the complexities that embody this wound.”

The first “street” museum launched in the public square in Lexington in October 2018 – once one of the larger slave auction sites in the United States.

“Initially, property owners in the immediate vicinity permitted their windows to become part of the memorial project,” Guyon said. “After the launch, the installations spread throughout downtown.”

The project has received a $20,000 grant from the National Endowment of the Arts to create a citywide library installation. It also received the American Association of State and Local History Award of Excellence for achievement in the interpretation of state and local history and a grant from Kentucky Humanities.

“One of the foundational precepts of the project is to take the humanities out of the museum, the university and the art gallery, and bring them onto the street so citizens come face-to-face with a visual history lesson rarely if ever, encountered on the streets of America,” Burton said. “The goal of commemorating a legacy of abuse, violence, and pain presents certain challenges. ‘I Was Here’ meets these challenges in an eloquent, reverent, and respectful way.”

Syndy Deese has been a volunteer on the project since 2018. She said she “instantly felt the ancestor spirits” and knew in her heart the project would touch many lives and begin to shape how people see one another.

“It’s important to me that we acknowledge the history and the pain of our past, yet work toward a future with a shared humanity for all citizens,” Deese said.

Winning an award in the CODAWorx budget category is interesting, Deese said, adding people that believe in public art and its power are able to accomplish such things with very little funding.

“The artists involved did not receive personal payment,” Deese said. “The project was not commissioned by an art funder, but by an American citizen who wanted to shift the spirit of our country. This is a million-dollar project, but it occurred without significant funding because the need is so urgent.”

Mary Quinn Ramer, president of VisitLex, the city’s tourism office, was a financial sponsor to “I Was Here” and said she spoke to the project team about the racial and other divisions tearing the country apart.

“We kept thinking there has got to be a different way for us to have a conversation,” Ramer said. “‘I Was Here’ is something that really serves as a national template and a cue that can be taken for any community to finish telling the rest of the story, and in a way that allows everyone to bring their humanity to the discussion.”

In the early stages of development, Guyon mentioned the project to a friend at Wells Fargo Advisors and soon learned Wells Fargo Advisors and Wells Fargo wanted to get behind the effort.

“‘I Was Here’ fits our vision, values, and goals at Wells Fargo, including a shared commitment to diversity and inclusion, corporate citizenship, and team member engagement,” said Vincent Hill Sr., a senior vice president for Wells Fargo Advisors Diverse Client Segment Team.

Ultimately, Wells Fargo Advisors and the Wells Fargo Foundation provided grants to support the project.

Along with funding the creation of the art, the company sponsored a pre-launch reception, financed the creation of a brochure with a locator map and detailed information about each portrait.

Bob Estes, the owner of one of the local businesses displaying the shades, said the exhibit has provided a way for people to move forward. “‘I Was Here’ has generated a lot of conversations that are not always easy between people, but opened the doors for people to talk about slavery and what happened here (in Lexington) and provide a forum for reconciliation,” Estes said.

This year’s 446 CODAawards entries represent $141 million in commission fees, and projects from 30 countries. A jury of 18 esteemed members of the design, architecture, and art worlds were tasked with grading the projects.

“The CODAawards recognize the importance of collaboration, and honors design and art professionals whose collective imaginations create the public and private spaces that inspire us,” Sikes said. “When artists, designers, industry resources, work together, common places are transformed into spectacular spaces. CODAworx, the hub of the commissioned art economy, fosters the relationship between artists and resources. This year’s CODA awards winners exemplify the best of what can happen when artists a and design professionals come together to create artful spaces in the built environment."

Craig Cammack, Community Outreach Liaison for LGBTQ Relations, Neighborhood Engagement, School Partnerships and Veterans Affairs for the city of Lexington, said city officials are proud of “I Was Here.”

“The ‘I Was Here’ public art project is a wonderful asset to our community and continues to receive international acclaim,” Cammack said. “Congratulations to this creative team.”

Expanding the project’s presence to more cities will require more funding, Guyon said. Donations toward the project may be made at i-was-here.org.

Information about the 2020 CODAawards is available on CODAworx.com. The award-winning work will also be featured in an exhibition at the Octagon Museum in Washington, D.C., in the summer of 2021.