LEXINGTON, Ky. — If one is lucky enough to find some ginseng or other sought-after roots and herbs in the mountains of Appalachia, chances are one would have little trouble selling it. It can be a difficult and often arduous task finding and harvesting ginseng and the like, but digging in the dirt could translate to rolling in the dough.

What You Need To Know

- Ginseng becoming more scarce

- Demand in China at all-time high

- Selling medicinal roots and herbs can be lucrative

- A license is required to be a ginseng dealer in Kentucky

Finding and harvesting ginseng

Ginseng is plentiful in Appalachia, but cultivating it is not an easy task. The harvest of wild ginseng is regulated in 19 states, including Kentucky, and is restricted or prohibited in all other states. Kentucky’s designated harvest season is Sept. 1 to March 31, according to Kentucky’s American Ginseng Management Program administered through the Kentucky Department of Agriculture.

Anthony Tackett, a teacher and football coach at Belfry High School in Pike County, has spent most of his life going in and out of the woods searching for, and often finding, ginseng.

“I’ve been doing this since I was a little kid,” he said. “We were taught how to do it and it’s just something that you did. It’s really been a part of my life. My great-grandfather grew ginseng. He had patches of it and he died in 1940. Those patches are still on my property.”

Ginseng usually grows in well-shaded areas of moist hardwood forests. The more mature the forest – with large hardwood trees and a full canopy—the better for ginseng, as a thick understory of smaller plants will over shade or compete with ginseng plants.

Once a mature ginseng plant is located, the delicate process of digging begins. A pitchfork or needle-nose spade is typically used to dig under the plant and remove the root. The roots are then soaked in a bucket of cool water to remove excess soil and placed in a single layer on a screen tray or wooden rack to dry for about two weeks.

According to the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, the demand for ginseng in China is so great that wildlife managers worry that wild American ginseng could be on a path toward extinction, although other than common anecdotal reports of ginseng being more difficult to find, no one knows exactly how much exists in the wild.

“Anyone in the trade will tell you that compared to when they started, it’s getting harder to find these plants in the wild, and the ones they do find are smaller,” said Randy Cottrell, a special agent with the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service. “The days of finding large roots are pretty much gone.”

Roots and herbs are still big business

While many people dig for ginseng and other roots and herbs to use medicinally, most gatherers do it for the money, which can be lucrative. Appalachian-grown ginseng is prized in China and has sold for as much as $9,000 per pound.

Other roots and herbs that are plentiful in Appalachia are also mostly sold to China, where it is used in tea and a myriad of other products, and countries in Europe.

“The whole thing has gone so far now beyond ginseng,” Tackett said. “It is crazy what is marketable that grows here. There are a lot of people here that do this and it’s a global market.”

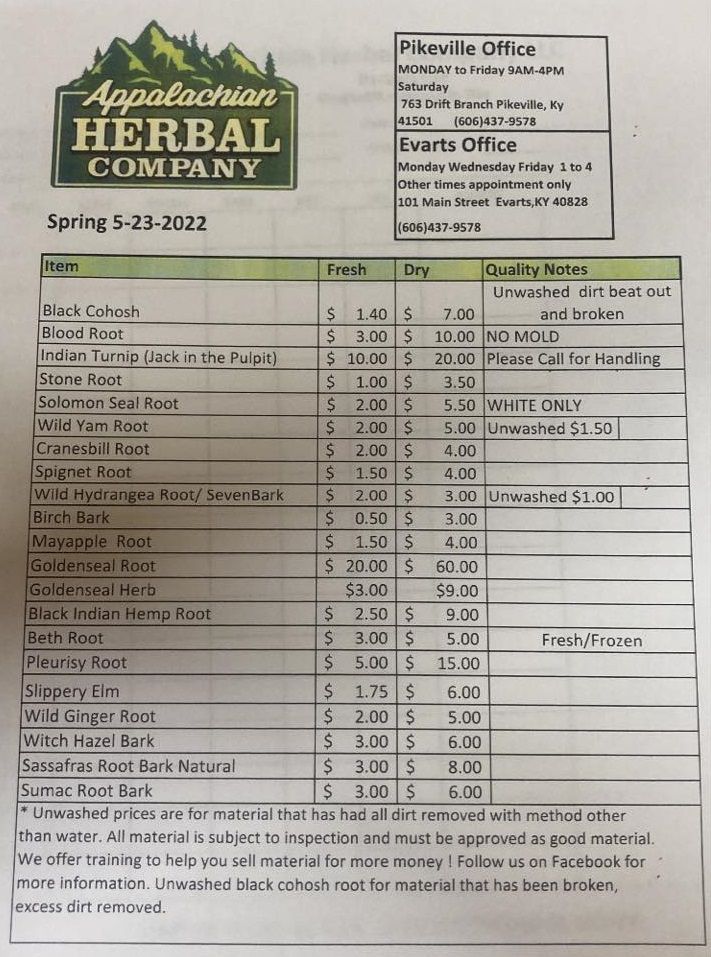

The more recent list of what Appalachian Herbal Company is paying for certain roots and herbs. (Appalachian Herbal Company)

Tackett said he has looked beyond ginseng partly because it had gotten so popular and valuable that everyone started digging it and it became more difficult to find.

“We have lost so many jobs here with the decline of the coal industry,” Tackett said. “People started digging for ginseng more and more and it’s just harder to find. It has been dug almost too much. China will buy every bit of ginseng it can and pay top dollar for it. With a market like that, it’s no wonder so many people dig for it.”

While laws have been enacted to combat the practice of poaching ginseng, Tackett said legislation is not likely going to stop the problem.

“Poaching was a problem before there was a problem,” he said. “For a long time, there were no laws in Kentucky — you could dig as soon as it came up until the last leaf dropped off in November. But there are some federal laws that say you can’t dig it at all to try and bring it back.”

Although moving away from digging ginseng, Tackett has hardly stopped venturing out onto his property in search of valuable roots and herbs. He said he now looks for rattle weed, cherry bark, slippery elm, sourwood leaf, witch hazel and witch hazel leaf, poke and poke berries, goldenseal, hydrangea, stone root, black Indian hemp and others.

“It’s crazy how many things you can find here,” Tackett said. “I am growing a lot of this stuff on my property because I’m thinking about my kids and grandkids down the road. This would be something very beneficial to my family if I can learn to grow this stuff organically. Many of these things are way more than gyms right now — there’s just so much more opportunity with the other stuff than there is with just ginseng. Digging ginseng is awesome, but I’m telling you, it’s tough.”

Tackett sells his wild harvested medicinal herbs and ginseng to the Appalachian Herbal Company in Pikeville, Ky., which has partnerships with the Wilcox Drug Company in Boone, N.C., and Muggenburg in Hamburg, Germany.

“It’s crazy how much money you can make from something like slippery elm,” Tackett said. “You can sell the twigs, sell the bark and cut the trees and sell them for firewood. You’re getting a lot for it and if you can grow this and get on a cycle to where this is something you can year after year after and not destroy the resource, then, you are in business.”

A license is required to be a ginseng dealer in Kentucky.

This is the second of a two-part series of articles about ginseng and other roots and herbs, and their history and connection with Appalachia.