At the start of the pandemic, hundreds of thousands of Kentuckians learned that their jobs made them essential. As the months go by and the pandemic continues, many now say they don't feel so essenial any more. While employees are feeling the stress and strain, some of Kentucky's largest employers are benefiting from their front line workers. In a special series of reports Adam K. Raymond talks to essential workers about what the last year has been like and where these positions and companies are heading into the future as the pandemic continues.

‘Essential’ no more: Kentucky front-line workers on life in the pandemic

(Kroger)

(Kroger)

LOUISVILLE, Ky. — It was around mid-March of 2020 that Mason Sims was first called “essential,” a label the pharmacy technician and cashier wore with pride.

“A lot of employees recognized how essential our jobs were, but it was good to know the public was starting to realize it,” said Sims, who worked at a Lexington Kroger when COVID-19 hit Kentucky.

With the label came newfound appreciation. Sims recalled the early days of the pandemic, as anxious customers stood in long lines to bring home essentials, unsure of when they'd next be able to go to the grocery.

"We had a mutual understanding," he said. "I’d apologize and they’d be like, 'I understand. Thank you for doing what you do.'"

Before the pandemic, Sims was used to people passing through his checkout lane and never looking up from their phones. They avoided eye contact. “They don’t want to really acknowledge that the person who’s waiting on you is a human being,” he said.

By last summer, that behavior had returned. "People were angsty,” Sims said. “It was like, ‘We don’t really care anymore.”’

A few months later, as the weather turned cold and Kentucky’s COVID-19 death count spiked, the gratitude was gone entirely. Workers were still exposing themselves to potential illness, but customers grew defiant, dropping their masks and demanding a level of service that felt impossible to provide.

Now, halfway through 2021, workers once lauded for their contributions to society are back to being ignored, or in some cases, berated by customers. “They’re either not paying you any mind or they're being really short with you,” Sims said.

Sixteen months ago, hundreds of thousands of Kentucky workers were deemed “essential.” As millions of Americans lost their jobs and millions more began to perform theirs remotely, essential workers found themselves in limbo — spared from the uncertainty of unemployment but deprived of the safety that came with working from home.

Initially, they drew praise for going out in the world to allow the rest of society to continue functioning. Gov. Andy Beshear celebrated their heroism and, in some cases, their bosses boosted their pay. Yard signs honoring their service popped up like dandelions, concerned citizens donated hand-sewn masks and companies such as Starbucks and Crocs offered “thank yous” in the form of freebies.

For Shaun Judd, the essential label was confirmation of something he’s long known.

For the past two years, Judd has worked at Baptist Hospital in Louisville, preparing supplies for doctors going into surgery. When the first COVID-positive patients arrived last year, the hospital took great pains to protect workers from the then-mysterious virus. Hallways were closed, barriers were erected and doctors did their jobs in bodysuits and hoods. “It was very scary,” Judd said. “You’d think, if I enter this hallway I might get COVID.”

But he understood why he was at work. “Not to brag or anything, but I feel like my job is very important,” he said.

Each day when Judd drove into work, he saw a sign acknowledging as much. Stuck in the grass outside of the hospital were big, bold letters reading "Heroes Work Here."

Recently, with construction going on at the hospital, the sign came down. “No one ever said 'We're going to take this down,' or 'We're done with this,'” he said. "It just faded away."

For Carolyn Tinsley, being called essential was "strange."

“It was the first time I’ve ever heard it, but going to work during a bad time was not new to me,” said Tinsley, a nursing instructor at Murray State. “I’ve always been essential.”

In the classroom when the pandemic hit, Tinsley left Western Kentucky for North Dakota last summer. She spent 13 weeks treating COVID-19 patients in an ICU. Apart from signs calling her a “hero," she noticed very little celebration for the job that kept her and other nurses away from their families and under immense pressure.

“I worked with nurses who couldn't go home and hug and kiss their children because they had worked COVID, and that’s not new,” she said. Neither, according to Tinsley, is the lack of public acknowledgment for the sacrifices nurses make. “I wish that people had a better appreciation for what nurses do every day,” she said.

Other essential workers had a hard time accepting the label. Karl-Heinz J. Williams, a tech supervisor for Ken’s Beverage who lives in Meade County, works on coffee and fountain drink machines at gas stations, restaurants and nursing homes. It’s a job that he doesn’t see as essential to the functioning of society, despite its designation as such last year.

“When I think of essential workers, I think of hospital workers, police, EMS — people that actually need to be out working,” he said.

If people in those roles worked throughout the pandemic out of necessity, Williams saw a different reason for his continued employment. “I always thought it was greed,” he said. “Somebody said we were essential so they could keep making money.”

An analysis early in the pandemic found that there were 422,000 essential workers in Kentucky. While just over half of the group was front-line health care workers, it also included nearly 50,000 trucking and warehouse workers and twice as many people working in grocery, convenience and drugstores.

Being called essential when his work didn’t feel that way frustrated Williams, particularly when he found himself in unsafe settings.

“We were touching stuff that everybody was touching and you didn’t know who washed their hands or who was taking the precautions they needed to,” he said. “It was a constant worry of if I’m going to be safe, or if I’m going to catch this.”

By the time Noah Smith went to work at Breadworks in Louisville last October, the notion that essential workers were worthy of special appreciation had largely vanished. COVID-19 hadn’t, though.

“This was before the vaccines were out,” Smith said. “This was high stakes.”

Smith’s employer helped reduce the risk of exposure by removing tables from the shop. That and the cancellation of the bakery’s New York Times subscription meant no customers were lingering around, making messes that later needed to be swept up. But new problematic behavior emerged, with some customers treating the mask requirement as a loose suggestion.

The low pay — Smith made $10 an hour — along with the threat of COVID-19, resulted in an ever-present sense of dread. “There was a layer of terror over everything,” Smith said.

Surveys conducted last year consistently showed that essential workers suffered adverse mental health effects of continuing to report to work during the pandemic. In June of 2020, a Kaiser Family Foundation survey found that essential workers were nearly one and half times more like to suffer from anxiety or depression than nonessential workers. They were more than twice as likely to rely on substances to cope with stress and nearly three times as likely to have recently considered suicide.

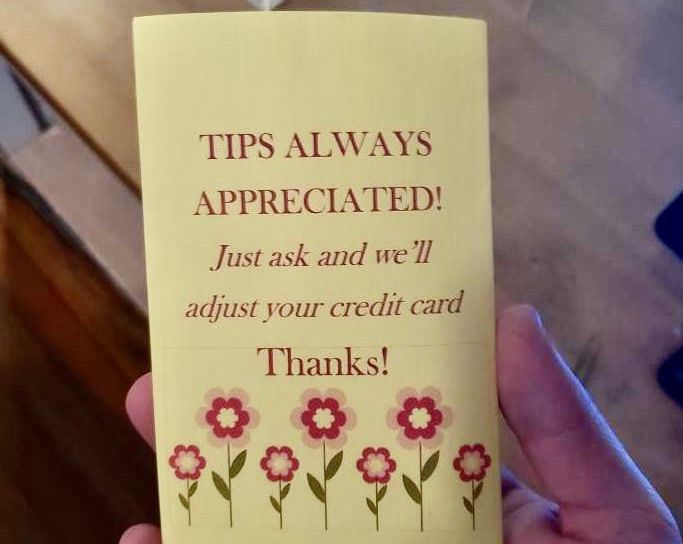

Adding to Smith’s stress was a change in customer behavior from before the pandemic. “No one was tipping,” they said. This was Smith’s second stint at Breadworks. Smith used to collect $60 a day in tips, but that dropped to $13 last fall.

“One guy was like, ‘Keep the change,’” Smith recalls. “I took the change, and he was like, ‘Not the dollars.’”

Smith has since left Breadworks for a job at the University of Louisville. Sims has taken a new, better-paying position as a pharmacy tech, though he still picks up shifts at Kroger on some weekends. Tinsley will soon begin teaching again, while Judd and Williams continue reporting to work on the frontlines, just like they did every day of the pandemic.

'It's not right': Essential workers got 'thank you' pay as CEOs got millions

One of the many Kentuckians working at Amazon (File Photo)

One of the many Kentuckians working at Amazon (File Photo)

LOUISVILLE Ky. — Financial struggles have defined the past 18 months for the Americans hit hardest by the pandemic, from those who couldn’t afford to bury their loved ones to those who saw their businesses crumble. But many companies deemed “essential” early in the pandemic have a different story to tell.

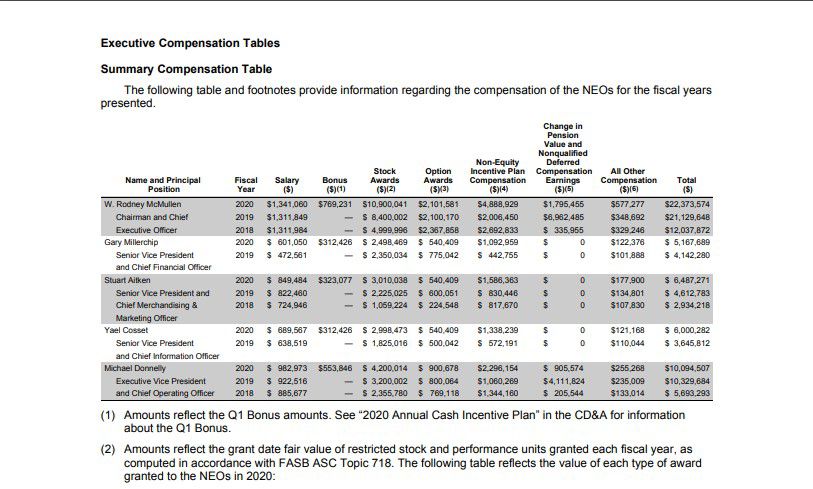

Not only did the biggest essential businesses in Kentucky survive during the pandemic, but they also thrived. In the second part of a three-part series on life as an essential worker in Kentucky, Spectrum News 1 looks at how the pandemic benefited three major Kentucky employers — Amazon, Kroger and UPS — and how those benefits flowed mostly to executives at the top.

It’s hard to imagine a bigger winner during the pandemic than Amazon. The e-commerce giant hit $386 billion in sales last year, up more than $100 billion over 2019, as consumers shifted even more of their buying to online retailers.

Like many states, Kentucky is home to tens of thousands of Amazon employees who work at facilities from Hebron to Campbellsville.

Early in the pandemic, Amazon acted quickly to reward those workers for staying on the job while many Americans stayed home. In mid-March of 2020, the company temporarily added $2 to the hourly wages of what it called "our Amazon retail heroes." In June of 2020, it paid a $500 “Thank You" bonus, and those with the company at the end of the year received a $300 holiday bonus.

Chris C., who asked that his last name not be used, began working as a stower at a Louisville Amazon warehouse in January. “I was a later employee in the quote-unquote essential worker era,” he said.

But Chris did not miss out on the COVID-19 era. In fact, he began working at Amazon during the state's deadliest month of the pandemic, when COVID-19 was killing an average of 35 Kentuckians a day. Vaccines were only available for health care workers and the elderly, making it one of the riskiest times to work in a crowded warehouse. Chris said Amazon took safety seriously, but hazard pay and appreciation bonuses were in the past.

The orders, however, kept coming. As a stower, Chris was responsible for packing small boxes filled with products into larger containers that would go on a truck. “My feet would hurt bad. I’d come home with calluses,” he said. “But you'd still be expected to hit these absurd rates, around 320 packages an hour.”

A busy Amazon meant a higher Amazon stock price, which sent the net worth of founder Jeff Bezos soaring. Chris said he and his co-workers mostly joked about Bezos, reserving their ire for their immediate supervisors. Still, he can see why others might not be laughing.

“I can completely understand how people are very, very mad that Bezos almost doubled his wealth during the COVID-19 pandemic, while other people struggled to survive,” he said.

Bezos has indeed seen his net worth grow by nearly $100 billion since the start of 2020, according to Bloomberg’s Billionaires Index. In the past several months, he’s cashed some of it in, too, selling more than $6 billion worth of Amazon stock ahead of his July 5 retirement. Meanwhile, in all of 2020, Amazon spent $2.5 billion on bonuses and incentives for its more than one million global employees.

Amazon’s success during the pandemic helped buoy other companies, including United Parcel Service, Louisville’s largest employer.

In 2020, UPS recorded a record-breaking $84.6 billion in revenue, a 14% increase over 2019. The growth, like Amazon’s, was attributed to the pandemic-led e-commerce boom.

Unlike Amazon, though, UPS did not reward workers with bonuses or hazard pay tied to the pandemic, according to spokesperson Jim Mayer.

“We’ve offered bonuses off and on for years,” he wrote in an email. “We have not adjusted pay specifically as a result of the pandemic, but rather market conditions. If the flow of applications isn’t what we need it to be at a given time, we will enhance incentives."

The lack of hazard pay resulted in multiple petitions calling on the company to provide it. One, launched early in the pandemic, received nearly 300,000 signatures.

Despite not offering hazard pay, UPS did provide two weeks of paid sick leave for workers sick with COVID-19 or quarantining after exposure. It also thanked its drivers with tweets.

UPS had two top executives during the pandemic, and they were both rewarded handsomely. David Abney, who had been with the company for 46 years, retired on June 1 and received a $5.84 million compensation package for his five months at UPS in 2020. His replacement, Carol Tomé, pocketed $3.78 million, for a total of $9.6 million between the two executives in 2020.

While UPS and Amazon thrived last year because people stayed home, Kroger was the beneficiary of their rare trips out.

The country's largest supermarket chain, which employed more than 21,000 people in Kentucky as of 2018, saw sales jump to $132 billion, an 8.4% increase over the prior year.

Like Amazon, Kroger responded to the pandemic by instituting a period of hazard pay and a series of bonuses, including a $300 “appreciation bonus” in March of 2020 and a $400 “thank you bonus” in June of 2020.

Six months later, as cases surged, workers called for the return of hazard pay. “I guess we’re no longer considered heroes,” Mason Sims, who worked as a pharmacy technician at a Lexington Kroger last year, told Spectrum News 1 in January. The following month, Kroger gave front-line workers $100 in store credit and 1,000 fuel points. At the time, the company boasted of spending $1.5 billion on "COVID-related reward and safety measures."

Sims and his co-workers never saw hazard pay renewed, but he did learn the company’s CEO, Rodney McMullen, raked in $22.4 million in compensation in 2020, a $1.2 million increase over 2019.

“I wasn’t surprised because it happens every year — the top gives themselves a raise and ours stays the same,” he said. “It’s not right." A Kroger spokesperson did not respond to a request for comment.

Sims said the slight from McMullen was especially insulting because the executive has roots in Kentucky. "He was a University of Kentucky student and he started out with Kroger," Sims said. "He loves to share the story about how he bagged groceries, worked in all these different departments and worked his way up to become CEO, but he forgot about all of us along the way."

'It's not worth it to me:' How the pandemic is changing the jobs of essential workers

LOUISVILLE, Ky. — Each day after she clocks in at a Central Kentucky clothing warehouse, and again before leaving, Caren Lamblin sanitizes her workstation. Even as safety protocols are relaxed — now that she’s fully vaccinated, Lamblin is allowed to work without a mask — it’s a ritual that lives on.

“It used to be, if you got a chance to wipe off your counter, great,” Lamblin said. “Now it’s the first thing you do and the last thing you do. It’s normal now.”

After nearly a year and a half of working under unprecedented pressure, essential workers are now experiencing a host of changes to their work lives. Employers are emphasizing cleanliness and offering higher wages, with workers gaining more power than they had before the pandemic. As the COVID-era starts to fade, along with the notion that front-line workers are “essential,” several Kentuckians who never stopped reporting to work during the pandemic told Spectrum News 1 that they hope many of these changes are here to stay.

“I do have a sense that the ball is starting to be more in the worker’s court, rather than the company’s,” said Mason Sims, who worked at Kroger throughout the pandemic. “But I don’t think we're fully there yet. We’re still struggling on the front lines.”

Throughout the pandemic, some companies helped ease that struggle by offering hazard pay and bonuses. Those eventually expired, but the idea that workers were worth more than they were getting did not. Soon, McDonald’s, Costco and Walmart were among the major employers to announce hikes in their minimum wage. Some other companies, including Louisville’s largest, UPS, followed suit as the labor market tightened this summer.

Sims, who recently left Kroger to take a higher-paying position doing the same work for a different company, said employees understand their worth better now than they did before the pandemic.

“No one is going to want to come back to a job that pays less than $15 an hour to be yelled at and treated like crap,” he said.

While some people move to better-paying jobs as essential workers, others have left the front lines entirely.

That’s what Noah Smith did. After several months last winter working the counter at Breadworks, a Louisville bakery, Smith began a job at the University of Louisville in February. It’s the type of position that doesn’t require confronting cranky customers or fighting for tips. “I will never, never go into a work setting like that again,” Smith said. “It's not worth it to me.”

Chris C., a former Amazon employee who asked that his last name not be used, also left the front lines. After working in a warehouse for several months this year, coming home each day with sore feet and frayed nerves, he moved to a new position in data analytics, the field in which he hopes to spend his career.

These two Kentuckians are part of a national wave of workers evaluating their jobs and deciding to move on. A record four million Americans quit their jobs in April, according to the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics. The number dropped to a still-high 3.7 million in May. Stats show that many of these workers are leaving the front-line fields that never stopped during the pandemic, with retail, warehousing and food services among the sectors with the most departures.

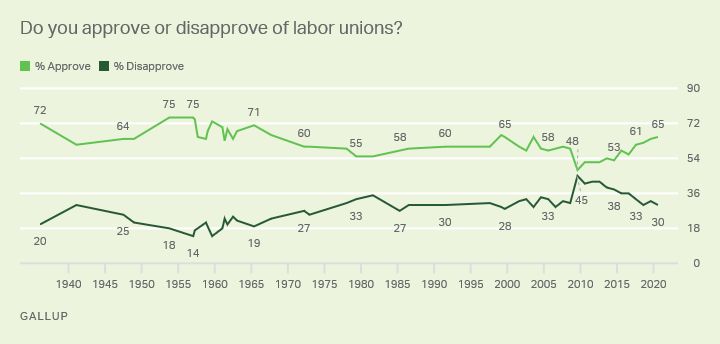

Union membership in the U.S. fell once again in 2020, the continuation of a decades-long trend. But due to higher job security for union members, the share of all workers who were in unions increased.

Now, some experts think the pandemic will lead to an increase in overall memberships. “The minimum wage remains at a measly $7.25, and the pandemic revealed that neither Federal or State OSHA are staffed and equipped to ensure the safety of workplaces,” said Ariana Levinson, a labor law scholar at the University of Louisville Brandeis School of Law. ”When workers are working in unsafe conditions for low wages, there will be an increase in unionization.”

Nonunion workers also saw unions step up for those on the front lines in the early days of the COVID outbreak. Before the pandemic was a month old, the United Food and Commercial Workers negotiated higher pay and improved benefits for meatpacking workers. Within days of the COVID’s arrival in the U.S., the Teamsters reached an agreement with UPS to provide sick leave to workers. By late summer, a Gallup survey found support for labor unions growing, with 65% of people saying they approve, the highest number in two decades.

None of this was enough for the most high-profile pandemic-era union drive to succeed, though. In March, workers at an Alabama Amazon warehouse launched a union drive that failed in its ultimate goal but inspired some Amazon employees in Kentucky to think about how a union could help them.

Few essential workers experienced the pandemic like nurses, who remain on the front lines as the Delta variant drives cases upward. Now, many are considering leaving the job behind. In April, a poll from Vivian Health, a job marketplace for health care workers, found that 43% of nurses are thinking of leaving the field in 2021.

Carolyn Tinsley, a nursing instructor at Murray State University who worked in a COVID-19 ICU last year, has some insight into why. Tinsley said her COVID-19 patients were “the sickest people I’ve ever seen in my life.” Treating them was grueling, she said, and required nurses to make great personal sacrifices.

On top of the physical and emotional toll, she felt like people weren’t listening to nurses. That's something she hopes changes in post-pandemic America.

“Nurses can help to teach the public,” she said. “Nurses are good at communicating and I think people trust nurses more than other people.”

In the early days of the pandemic, celebrations of essential workers were largely ceremonial. Now some states are celebrating these workers with programs that aim to improve their lives.

In recent months, several states have enacted measures aimed at rewarding essential workers for their sacrifice. Michigan’s Futures for Frontliners program provides free community college tuition to front-line workers who worked outside of the home between April 1 and June 30 last year. In New York, essential workers can apply for child care scholarships.

Kentucky, meanwhile, has not enacted anything similar. But that could change early next year when Gov. Andy Beshear has said he will encourage the General Assembly to pass an "essential worker bonus."