INEZ, Ky. — The residents of a small, rural county in eastern Kentucky are continuing their yearslong fight for access to clean drinking water.

What You Need To Know

- Martin County's water system has been plagued with problems for decades

- Lack of funds to fix crumbling infrastructure has hampered maintenance

- Attorney General in June announced plans to investigate

- Annual report shows water quality improving

Every community water system in Kentucky serving at least 25 residents year-round, or that has at least 15 service connections, must prepare and distribute an annual Consumer Confidence Report (CCR) which was released July 1, 2020. Clean water in Martin County has often been a topic of discussion since a coal slurry spill contaminated the area’s water supply in 2000.

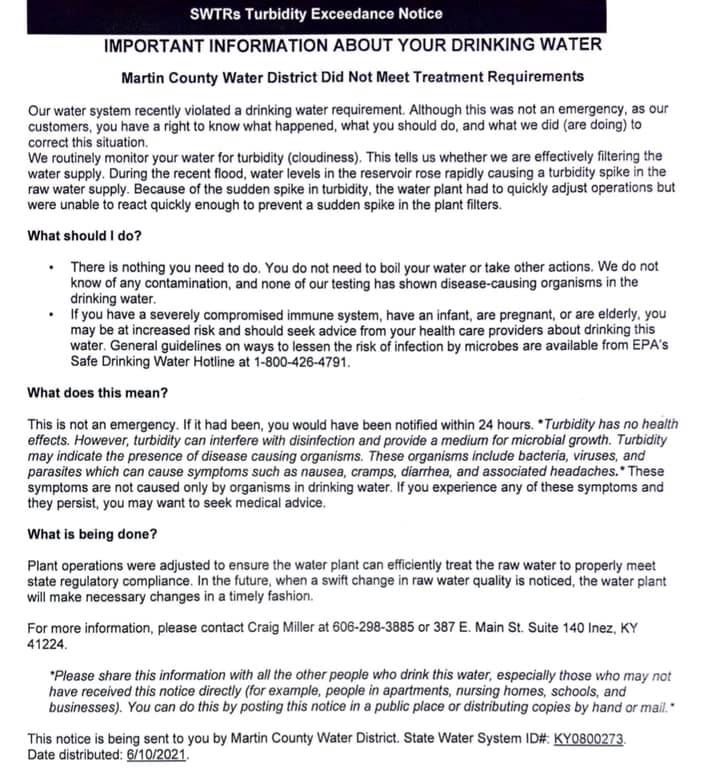

On Thursday, June 10, Martin County Water District customers received a letter stating the system had violated a drinking water requirement. The letter informed customers the violation was not an emergency and detailed what happened, what customers need to do as a result and what the district is doing to correct the situation.

“We routinely monitor your water for turbidity (cloudiness). This tells us whether we are effectively filtering the water supply,” according to the letter. “During the recent flood, water levels in the reservoir rose rapidly, causing a turbidity spike in the raw water supply. Because of the sudden spike in turbidity, the water plant had to adjust operations quickly but was unable to react quickly enough to prevent a sudden spike in the plant filters.”

)

The letter goes on to explain to customers they do not need to boil water or “take any other actions,” adding testing has shown “no known contamination or disease-causing organisms in the drinking water.” The letter does, however, suggest customers with compromised immune systems, those with an infant, who are pregnant, or are elderly may be at an increased risk and should speak with medical professionals about drinking the water.”

The district adjusted plant operations to comply, according to the letter.

Among Martin County's past water issues are leaks, contamination and inoperable water-token kiosks, according to previous reporting by Spectrum News 1's Khyati Patel and Joe Ragusa. The turbidity spike is the more recent problem to plague the water system in the small, rural coal-mining county with around 13,000 residents across the Tug Fork River from West Virginia, according to those reports.

Comparing Martin County's water

The 2020 CCR report explains how Martin County Water District treats surface water withdrawn from Crum Reservoir and replenished from the Tug Fork River. Additional finished water is purchased from Prestonsburg Utilities to supply water to the county’s industrial park. The source for Prestonsburg is surface water from the Levisa Fork of the Big Sandy River.

According to the 2020 CCR report, potential contaminant sources of concern in Martin County include major roads, bridges and culverts, and the coal, oil and gas industries and straight pipes used to dispense household sewer. Many of the potential contaminant sites are located along the Tug Fork River, according to the report.

With each rainfall, herbicides, pesticides, fertilizers, animal manure and household chemicals are washed from impervious surfaces and other land areas into storm drains, ditches, sinkholes or streams that flow into our nearby waterways, according to the report. Source Water Assessment Plans referenced in the report have been developed for both water systems and are available for review at each of the respective water system offices and local public libraries.

The Martin County Water District’s 2020 CCR showed no violations in any of the major categories, which are radioactive contaminants, inorganic contaminants, disinfectant byproducts and precursors, household plumbing contaminants and other constituents, such as turbidity.

“No matter the size of the utility, we are all regulated the same,” said Kelley Dearing Smith, vice president of communications and marketing for the Louisville Water Company. “We are regulated by the EPA, so the regulations are the same for my hometown in Fleming County as they are here in Louisville.” Smith compared testing water samples to a science project in school because the time of the day, the source, the temperature of the water and whether the pipes were flushed prior are variables considered.

“Drinking water, including bottled water, may reasonably be expected to contain at least small amounts of some contaminants,” according to the 2020 Martin County CCR. “The presence of contaminants does not necessarily indicate that water poses a health risk.”

The World Health Organization (WHO) said that the amount of fluoride in drinking water is important because excess fluoride can cause fluorosis — a cosmetic condition that affects teeth and bones. Long-term ingestion of large amounts of fluoride can lead to potentially severe skeletal problems, according to the WHO. Low levels of fluoride in drinking water can helps prevent dental and skeletal problems. "The control of drinking-water quality is therefore critical in preventing fluorosis," according to the WHO.

The maximum contaminant level of fluoride in drinking water is four parts per million (PPM) or milligrams per liter of water. The highest reported level of fluoride in Martin County was .88 PPM in April 2020. The highest level of fluoride detected in water by the Louisville Water Company, which treats water drawn from the Ohio River, was .6 PPM. Nitrate levels in Martin County, typically caused by fertilizer runoff, sewage leaching and the erosion of natural deposits, were reported to be .14 PPM while the level was 1.0 in Louisville’s water. The 2020 CCR for Fayette and surrounding counties, which draws its water from the Kentucky River, showed the highest fluoride level at .93 at its Kentucky River Station II treatment plant and nitrate at .57.

In Eddyville, a town of about 2,500 and the seat of Lyon County in western Kentucky, fluoride was reported at .88 PPM at its highest and nitrate at .65 PPM. In contrast, the city of Ashland along the Ohio River in northeastern Kentucky reported levels of .42 PPM and .576 PPM of fluoride and nitrate, respectively.

None of the CCRs used in researching this story violated any of the minimum standards set by the Kentucky Division of Water. The 2021 reports are due by July 1. Spectrum News 1 reached out to Pace Labs about having samples of water from Martin and other counties tested for this story. A spokesperson for Pace Labs recommended reviewing the district's respective CCRs to evaluate quality.

"As a lab, we do not offer comparisons or make determinations on drinkability," the spokesperson said in an email. "Also, this could be a conflict of interest for us if the sources of interest are our current clients."

CCR reports for 2021 are expected to be received in early July and will contain data from water samples taken in Martin County over the past year. Spectrum News 1 will follow up with that information after the new reports are reviewed.

Citizen scientists and a yearlong study

Researchers from the University of Kentucky and members of Martin County Concerned Citizens, an ad hoc group dedicated to giving residents “a voice in getting a fair price for water that is clean, safe and dependable,” according to its mission statement, began a yearlong pilot study of the county’s water in December 2018.

The study revealed Martin County’s drinking water regularly exceeded U.S. Environmental Protection Agency maximum contamination levels for cancer-causing disinfection byproducts and coliform bacteria. The pilot study was conducted by Jason Unrine and Wayne Sanderson, both professors in the UK College of Agriculture, Food and Environment, with funding from the UK Center for Appalachian Research in Environmental Sciences in the College of Nursing and the National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences.

The citizen stakeholder advisory board of UK-CARES connected the researchers with Martin County Concerned Citizens. The professors and citizen scientists from the group, including Martin County resident and retired biology teacher Nina McCoy, worked together on the pilot project, sampling drinking water and measuring it for contaminants in 97 homes.

Nearly all Martin County survey respondents reported problems with their drinking water, including odor, appearance, taste and pressure, with just 12% of respondents saying they drink the tap water. UK researchers said they found 47% of the samples had at least one contaminant that exceeded U.S. EPA regulatory guidelines.

“We found that there were frequent exceedances of U.S. EPA maximum contaminant levels (MCLs) for disinfection byproducts in the summer and early autumn, although the EPA regulates these contaminants based on a running annual average and not in individual samples,” said Unrine, a professor in the UK Department of Plant and Soil Sciences. “Disinfection byproducts are associated with increased incidence of adverse health effects, including bladder cancer and congenital developmental disabilities in epidemiological studies. Some of these studies have shown associations with these health effects from disinfection byproducts at concentrations that are similar to the average concentrations we measured in Martin County. It is important to note that the cancer studies assume lifelong exposure.”

Disinfection byproducts are formed when natural organic matter interacts with chlorine during the water treatment process. Ten percent of the samples obtained exceeded maximum contaminant levels for haloacetic acids, and 29% exceeded the maximum contaminant levels for total trihalomethanes — both are disinfection byproducts. According to the study, concentrations of haloacetic acids were higher in homes farther from the drinking water treatment plant.

The UK researchers also detected coliform bacteria in 13% of the drinking water samples, which is a type of bacteria that indicates the possible presence of harmful bacteria in the water. Researchers did not detect E. coli, which is closely linked to fecal contamination, and the drinking water had higher levels of coliform bacteria and disinfection byproducts during the summer and early autumn.

“We think the seasonal increase is due to several factors, including water temperature, the increase in algae and organic matter in the Crum Reservoir and Tug Fork River, and low water levels in the river and reservoir during these months,” Unrine said. “Future efforts at reducing disinfection byproduct exposure could address seasonal changes in source water chemistry and how adjustments to the treatment process and repairs to the distribution system might be made to reduce the formation of these compounds.”

McCoy said she had been told it would take $55 million to fix the water and sewer issues in Martin County. Aside from money, it will also require those in charge to start telling the truth, she said.

“The water district is going to have to be honest about what needs to be done,” McCoy said. “They're going to have to make sure that money gets spent in the right way. A few people have wanted to sweep this under the rug for years — we’ve been quarreling about this for 20 years — they keep saying everything’s fine and not worry about it. It finally just came to a head where it was just so bad it couldn’t even be maintained.”

Infrastructure is a problem

BarbiAnn Maynard lives with her family in Martin County near the border of Pike County. A member and de facto leader of the Martin County Water Warriors group, Maynard said she has routinely dealt with water that contains sediment, is brown, milky and has a foul odor.

“Different sources of water have different organisms,” Maynard said. “The water here in Kentucky is not the same as water in California or Florida. So, when they mix the chemicals to treat our water — we have living organisms in our river such as leaves, bugs, etc. — when they mix the wrong chemical and mixture, it causes a chemical reaction with those organisms. They are mixing in the wrong chemicals for our water. But it's cheaper to do, so it's a money thing.” Maynard said the water district recently spent $250,000 of grant money to purchase a new pump for the intake along the Tug Fork River. The new pump was supposed to have a rail system that allows the pump to be raised when the water level in the river rises.

“They can't afford the rail system,” Maynard said. “When it flooded in the spring, it flooded the new pump, and now it's useless.”

According to the American Society of Civil Engineers, drinking water across the U.S. is delivered through an estimated 1 million miles of pipes, many of which were laid in the early to mid-20th century and are nearing the end of their life spans.

A 2017 report by the group gave America’s water systems a near-failing grade, citing an estimated 240,000 water line breaks a year nationwide. The Martin County Water District reported 29 line breaks in 2017 and advised residents to boil their water in case of contamination.

The Martin County Water Warriors Facebook page contains hundreds of videos and pictures of people’s water. Martin County’s local newspaper, the Mountain Citizen, prompted the first state investigation into the Martin County Water District in 2002.

Tokens-for-water hits a snag

For some people in Martin County, getting water to their homes has been a challenge, but it was even more difficult for a couple of months earlier this year as at least one water kiosk machine was broken.

Many people in Martin County buy tokens from the water district. They insert them into a machine to fill tanks with water and haul it back to their home. With the machine broken, those residents had to find alternative ways of getting water.

Spectrum News 1 KY reporter Khyati Patel in a previous story spoke to longtime Martin County resident Sue McGinnis. McGinnis is among those seeking better access to clean water and a woman whose family depends on the water kiosk for most of its supply. The nearest source of water for McGinnis and several others is off the grid and accessible only by a winding dirt road. She repeatedly fills rain barrels on her property so not a single drop of water goes to waste, Patel reported.

Water-rate increase sought to improve system

Several improvements have been made to the Martin County water system over the past several years, but anxiety remains about water quality and now residents face a rate increase on top of what’s already one of the higher water bills in the state.

“We do not bring in enough revenue to pay our bills,” Kerr told Spectrum News 1 KY reporter Joe Ragusa in a previous story. He said decades of neglect left the county’s water system in shambles, leading them to increase water rates twice in the last three years.

Since then, several audits and investigations by the Public Service Commission have been conducted. In June, Kentucky Attorney General Daniel Cameron announced that his office would be opening an independent investigation into the water utility, specifically focused on alleged money mismanagement.

UK Environmental Health professor Dr. Anna Goodman Hoover said the problems in Martin County are “complex and range from infrastructural complexities to economic concerns to existing trust-related challenges.”