LOUISVILLE, Ky. — At Louisville’s Shawnee Park, the 129-year-old green space on the city's western edge, two grayish smokestacks stretch high above the expansive green canopy. Down below, on the Indiana side of the Ohio River, sits Duke Energy’s Gallagher Station, a coal-fired power plant that has spewed emissions into a borderless sky for more than a half century.

That ended on June 1, when Gallagher Station was officially retired.

“This is a really big win for us,” said Arnita Gadson, a Louisville environmental activist who has fought pollution and polluters for decades.

Though the plant has operated at reduced capacity in recent years, Gadson said its decommission and eventual demolition is a welcome development after decades of polluting Louisville’s predominantly-Black west end.

“I don't think people, even some people in West Louisville, realize the impact of that plant,” said Gadson, the Executive Director of the West Jefferson County Community Task Force and the Environmental Justice Director for the Louisville NAACP.

The retirement of Gallagher Station has been years in the making. In 2016, Duke Energy announced plans to end operations at the facility by 2022, but reduced demand due the pandemic accelerated the company’s timeline.

The ramp down at the plant began nearly a decade ago. In 2012, Duke Energy closed two of its four units and outfitted the other two with pollution control devices, including bag houses to reduce particle emissions and technology to drive down sulfur dioxide.

Those moves came after the company settled a federal lawsuit over Clean Air Act violations. According to the U.S. Justice Department, Duke Energy made making illegal modifications to the plant that “caused significant increases in sulfur dioxide," a pollutant known to negatively effect those with respiratory and cardiovascular diseases.

In addition to the changes it made at Gallagher Station, the settlement saw Duke Energy pay a $1.75 million civil penalty and spend millions more on environmental mitigation projects.

Over the years, Duke Energy's use of Gallagher Station dwindled and by 2020, the plant had reduced its pollution dramatically. Sulfur dioxide emissions were down 99.5% as compared to 1995, according to statistics provided by a company spokesperson.

Even at those low emissions levels, retiring the plant will be good for Louisville, said Rachel Hamilton, Interim Director of the Louisville Metro Air Pollution Control District (APCD).

“It will have an impact on equality,” she said. “Any pollution that is reduced is a benefit."

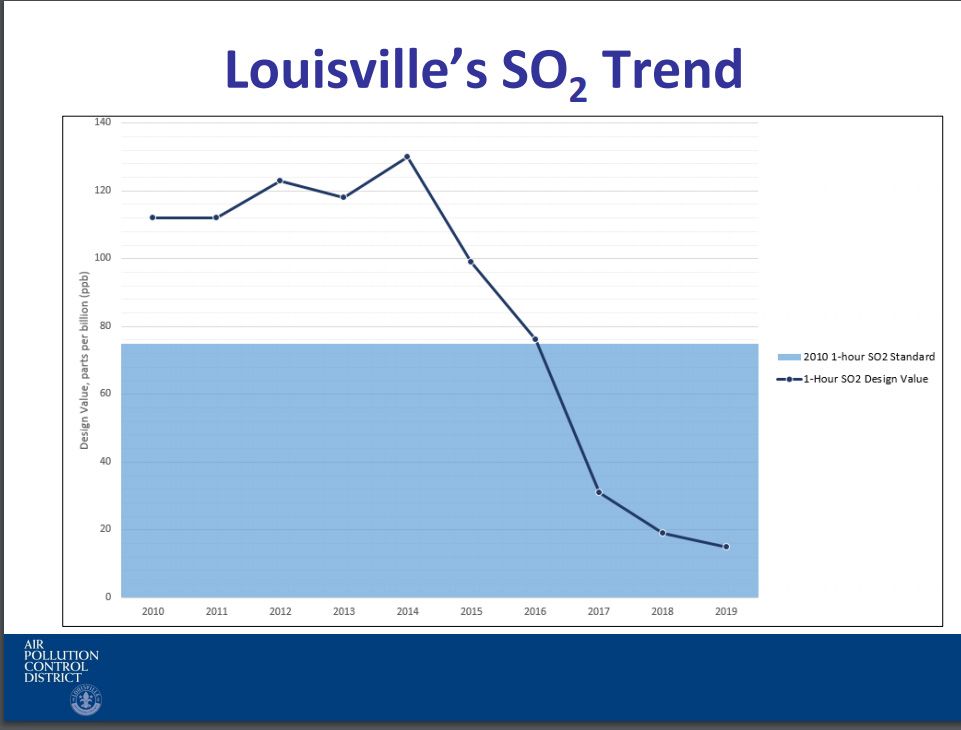

The past decade has already seen a steep decline in sulfur dioxide in Louisville, dropping from more than 100 parts per billion in 2010 to less than 20 in 2019, according to the APCD. That matches national trends that have seen sulfur dioxide emissions from power plants fall 93% between 1995 and 2020.

Pollution problems in Louisville began well before the Gallagher Plant opened in 1958. “We have pictures from just about a decade earlier of downtown Louisville where the sky just looks like it’s dark as night,” Hamilton said.

At the time, coal burning was ubiquitous — in homes, businesses and schools. Moving those emissions out of neighborhoods and into smokestacks was seen as an improvement.

Over time though, it became clear that pollution was leading to poor health outcomes. And in Louisville, pollution is not equally distributed.

“We don't have any coal-fired power plants in eastern Jefferson County,” said Tim Darst, an adjunct professor in the Bellarmine University Department of Environmental Studies.

Darst said that as the harmful effects of pollution became better known, many white people began to move away from Louisville’s west side. Due to racism and institutional factors such as redlining, Black Louisvillians had a harder time getting away.

This led to “a situation where people of color, as well as low-income people, bear the largest burden of air pollution, water pollution and soil pollution," Darst said.

That burden often manifests in poor health outcomes. A 2006 study from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention said long-term exposure to air pollution in West Louisville is associated with an increased risk of cancer. That same year, a study from he Environmental Integrity Project named Gallagher Station the "nation's dirtiest power plant" based on emissions of sulfur dioxide.

The site is also home to coal ash basins the Duke Energy is planning to close and monitor for decades to come. "We’ll have an extensive post-closure groundwater monitoring network for at least 30 years after the ash basin cloture activities are complete," spokesperson Angeline Protogere said.

The retirement of Gallagher Station is the latest positive development for Louisville's air quality. Louisville Gas and Electric’s Cane Run plant now runs on natural gas, rather than coal, and its Mill Creek generating station has undergone upgrades to reduce emissions.

“Air quality is improving,” Hamilton said.

But improvement is not all that’s called for, Gadson insisted. After decades of exposure to harmful pollutants, residents of West Louisville are owed more, she said.

Companies such as Duke Energy must find a way to “repair,” Gadson said. “And repair can be any type of reparation. If it’s not direct money, it’s opportunities. It's educational outreach.”

Last month, Duke Energy announced $100,000 in grants to nonprofits working on economic growth, food relief, and community beatification. The organizations receiving the money are all based in southern Indiana.