DODGEVILLE , Wis. — Brittani Stoney is currently working towards a life of sobriety in Dodgeville Wisconsin.

She said she has been sober for almost a year.

“I was an alcoholic for approximately 10 years,” said Stoney. “I abused my Adderall for about the same amount of time.”

Stoney is far from alone. According to the American Addiction Centers, in 2023, there were 48.5 million people struggling with addiction in the U.S..

As years went by, Stoney said her condition only got worse.

“I fell in with the wrong crowd and started using meth,” said Stoney.

She said it took her a long time to decide she wanted to be sober and start searching for viable rehab options.

“I got the chance to go to treatment court in Grant County,” said Stoney. “Honestly, it was one of the better things I have ever done.”

Stoney said she struggled to find a treatment program that suited her.

She said her mom had been trying to get her into treatment for years, but because of her insurance, she did not have much luck.

“Everyone she called would not accept me because I was not drug dependent at the time and they did not accept my insurance,” said Stoney.

Currently, Stoney is staying at the only nonprofit sobriety house in Dodgeville, Opportunity House.

“We are pleased to be able to offer eight people a place to escape from the street, homelessness or sleeping on the couch with a whole house full of people who are using,” said Kyle Wicks, who is a peer support specialist at the Opportunity House.

Wicks said for residents in Richland, Green, Iowa, Lafayette and Grant counties, Opportunity House is the only affordable option.

“Now, our space is somewhat limited because we struggle with being able to pay for the house,” said Wicks.

He said the only income that comes in to help Opportunity House is the $250 a month that residents are paying to stay there.

“If you add that up, that is $2,000 a month that this place has to run itself on,” said Wicks.

Brendan Saloner is a professor at John Hopkins School of Public Health who evaluates policies to promote access to health care and a stronger safety net for underserved groups, particularly for people who use drugs.

In 2021, Saloner and a team of professionals who study health policy conducted a survey of 613 rehabilitation programs nationally.

For the study, his team posed as uninsured cash-paying individuals using heroin and seeking addiction treatment.

Saloner said the study showed that there are often not enough spaces in nonprofit facilities, which creates a market for other providers to move in and offer services.

“That is not necessarily a bad thing,” said Saloner. “I think when you combine that with the idea that other providers are very expensive and some act in a predatory way, I think it creates a need for more public oversight and regulation of this industry.”

Soon, Opportunity House won’t be the only recovery option in Dodgeville.

Wood Violet Recovery is a for-profit rehabilitation center that is set to open in Dodgeville within the year.

Melissa Watson is the director of operations at Wood Violet Recovery.

She works directly with clients to find out which programs suit them best on their road to recovery.

“If at any time you have any questions or anything comes up feel free to ask, we will go ahead and take your stuff to your room and put it away for you after we search it,” said Watson while walking someone through the intake process.

Wood Violet Recovery has the ability to house 103 people at its new Dodgeville location.

James Mccomas is the executive director at Wood Violet Recovery. While Watson works directly with clients, Mccomas is in charge of the entire facility.

“We have medicated assisted treatments, we have 24-hour nursing here so when someone is going through the detox phase we have individuals, a physician, a provider office,” said Mccomas.

He said the facility offers everything from dual diagnosis to an outdoor pool and a workout facility.

“We try to create a family home environment,” said Mccomas. “We want individuals to feel safe. That is the first thing in any type of treatment program is for individuals to feel safe, secure and in a non-judgemental environment.”

Mccomas said they have a primary service area of three to five hours and cover multiple states including Iowa, Michigan, Illinois, Minnesota and Wisconsin.

“When someone is ready to go into treatment, you want to get them into treatment and we will actually go, pick individuals up and transport them back,” said Mccomas.

The study conducted by Saloner and his team found that for-profit facilities often use recruitment techniques such as offering to pay for airfare upfront or offering fancy amenities.

“What we found was financial inducements were dangled in front of folks and some of them were provided clearly to sweeten the deal,” said Saloner. “Paying for airfare up front or offering a lot of fancy amenities but not speaking to the medical or clinical value of the care.”

Through the study, Saloner said one-third of callers were offered admission within one day of calling a rehabilitation center and before a clinical evaluation was even conducted.

“If you are calling a hospital and they start telling you about all of these other bells and whistles that they can give you and can’t give you information about surgical outcomes, that would make me really worried,” said Saloner.

Saloner said for many struggling with substance use disorder, paying for these rehabilitation facilities can be difficult or even impossible.

“This is a huge financial burden for many families and what makes it even more concerning is there are not really great standards or markers for when people are finding quality care,” said Saloner. “This is a huge financial burden for many families and what makes it even more concerning is there are not really great standards or markers for when people are finding quality care,” said Saloner.

Saloner said many people end up paying for rehab with their own money and often have trouble getting their insurance to cover it.

The study looked at both for-profit and nonprofit organizations and found that “most programs required up-front payments, with for-profit programs charging more than twice as much ($17,434) as nonprofits ($5,712).”

Saloner said that number is only the up-front payment and said clients often end up spending much more.

“If a person stays in treatment longer than expected or they get certain services that are not quoted at the initial discussion, then that could even add further to the cost of the treatment,” said Saloner.

Wicks said everyone that comes through his doors wishes they could go to a bigger facility.

“To me and everyone else that has had to figure a way to get off the street or get the needle out of their arm or to get the pipe out of their mouth, it is a fantasy,” said Wicks.

Stoney said it is a fantasy that she never even considered.

She said she is grateful to have the support of the Opportunity House and worries that it won’t get the funding needed to keep the doors open.

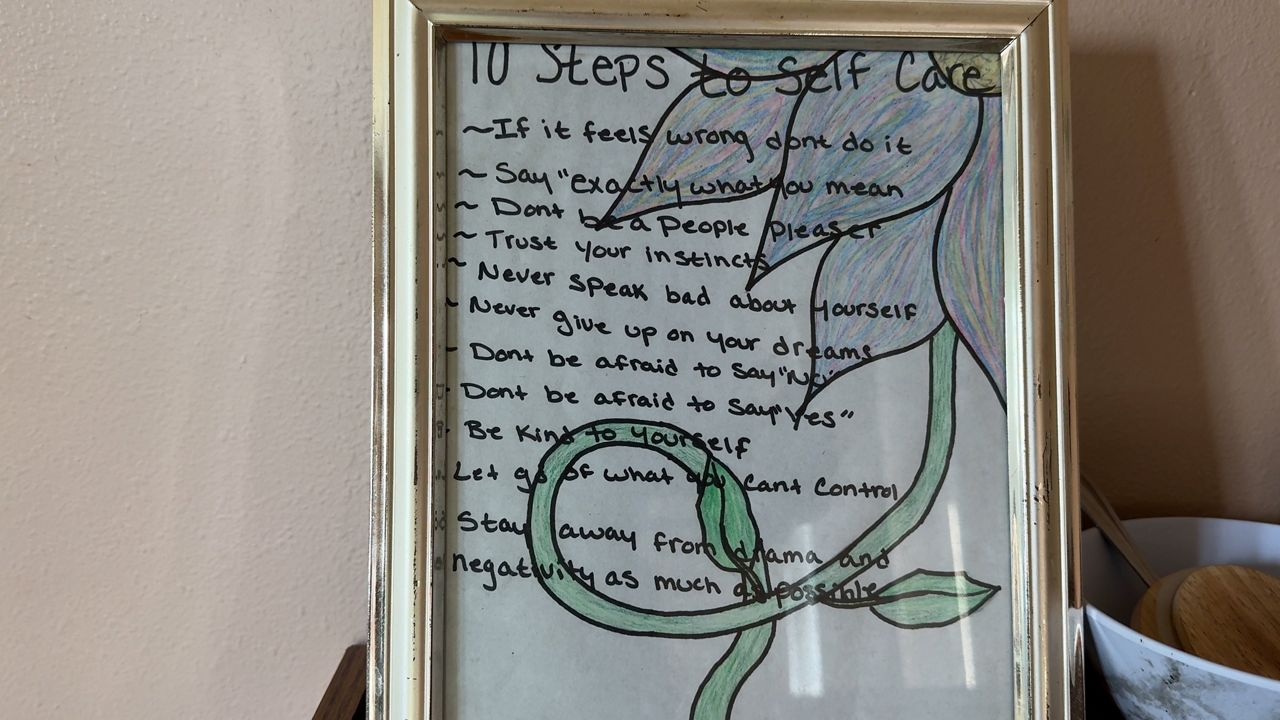

“Having this house is one of the biggest things because before here, I had not had a true place to call home where I was not using in like five to seven years,” said Stoney.

Stoney and Saloner said people should not get discouraged because good care does exist.

“There is really good care out there and people can get well and get better but going to a place where there is a fancy chef or a pool or therapy, all of those things might be nice but that is not really clinical care,” said Saloner.

He said these are some questions clients should be asking when calling a rehab center:

- Where am I going to be treated?

- Tell me more about the types of clinicians I can expect to provide treatment to me.

- What are some of the potential hidden costs I might encounter?

- What are your treatment outcomes at your facility?