MILWAUKEE — As Breast Cancer Awareness Month ends, a push in the Wisconsin Legislature to pass a bill that aims to increase access to potentially life-saving breast imaging continues as some lawmakers work to eliminate the patient’s share of the cost for screenings.

About half of women 40 years old or older have dense breast tissue, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). For them, a typical mammogram may not be enough.

However, when it comes to paying for additional screenings, including diagnostic, a study commissioned by Susan G. Komen for the Cure found out-of-pocket costs can range from an average of $234 to more than $1,000.

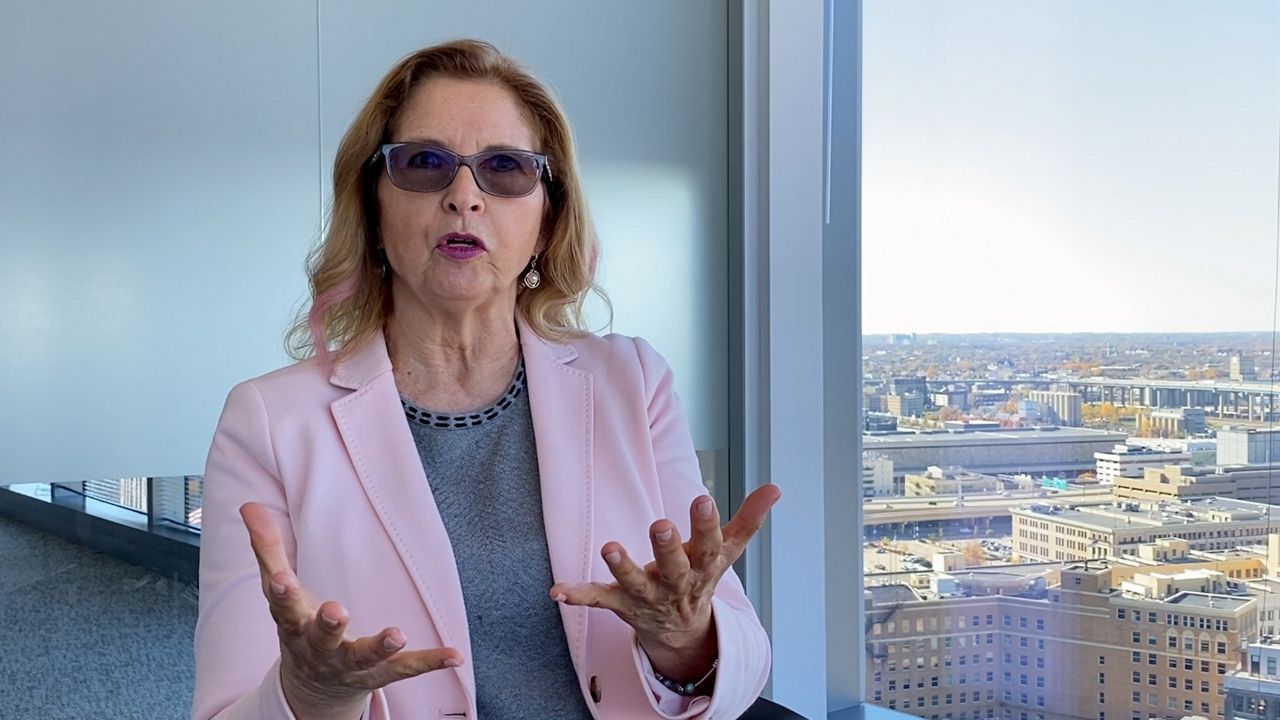

After being diagnosed with metastatic breast cancer, Linda Hansen was given 18 to 24 months to live—that was 13 years ago.

“There is no treatment. The doctors have been real clear with me—it will come back, and it will kill me,” Hansen said.

Hansen received the news after she said she followed the rules and began getting annual mammograms starting at 40 years old. However, Hansen didn’t know she had dense breast tissue or what that meant for her health.

“Dense breasts have nothing to do with your weight, size of your breasts, the feel of your breasts—nothing,” Hansen explained. “The only way you can find out if you have dense breasts is to have a mammogram and have them tell you.”

Hansen was told not to worry by her doctor, but five weeks after a clean mammogram in 2010, she learned she did have breast cancer and had it for quite some time.

“Dense breast tissue shows up white on a mammogram, and cancer, if you have it, shows up as white on a mammogram, and so what we’re essentially doing is looking for a snowflake on a snowball,” Hansen added.

Hansen’s diagnosis came before a state law was passed in 2017, and enacted in 2018, which requires patients to be notified by their doctor if they have dense breast tissue.

“The two laws in combination would have saved my life,” Hansen said. “And, if we pass this bill, other women’s lives are going to be saved. There is no question in my mind because right now, we’re missing half of all breast cancers on mammograms, and the vast majority of the ones that are missed are the ones in people with dense breasts.”

State Sen. Rachael Cabral-Guevara, R-Appleton, authored a bill that would require health insurance policies to cover supplemental or diagnostic breast exams for those with a higher risk of cancer at no cost to the patient.

Similar legislation was introduced in the past. However, there have been a few changes from the previous version of the bill, including:

- Reducing the $50 patient co-pay to zero

- Changing terminology to cover “supplemental screenings” as opposed to “essential screenings”

- Using the National Comprehensive Cancer Network guidelines to determine what is considered an increased risk

“If you’re going to say this is a preventative service that’s covered through your insurance company, a mammogram, but it’s not doing 100% preventative screening like it’s supposed to be doing, well then, we’re either falsely advertising and providing an exam that’s not doing its job thoroughly or we have to step up and make sure that all women are covered under that preventative service,” Cabral-Guevara said.

Hansen is concerned if women don’t have secondary symptoms or money to pay for a follow-up exam, they will go without.

“And what we’re doing by having these large co-pays associated with secondary screening is we’re dividing the women of this state into the haves and the have-nots,” Hansen explained.

“Those of us with metastatic cancer recognize that the work we’re doing will never help us, but it’s going to help our kids and grandkids. It’s going to help the next-door neighbor. It’s going to help the woman who hasn’t been diagnosed yet,” she added.

During a public hearing held in July, insurance companies expressed opposition to the bill and told lawmakers without a patient co-pay, costs could go up for everyone. Those in favor of the legislation, including Hansen, believe it would be cheaper to focus on prevention with treatment costs being so expensive.

While the bipartisan bill has yet to pass out of committee and receive a floor vote in either the Senate or Assembly, the legislation has been co-sponsored by more than one-third of state lawmakers.