For more on Electa Quinney, see our story on a school that still honors her legacy today.

MILWAUKEE — Almost two centuries ago, in a one-room schoolhouse on the Fox River, Electa Quinney made history.

As the schoolteacher for her Native American community, Quinney didn’t charge each student to be in her class. That means she was running the first-ever public school in the Wisconsin area — before these lands even became the Badger State.

What You Need To Know

- In 1828, Electa Quinney taught at the first public school on the lands that would become Wisconsin

- Quinney's story traces some of the path of Native American displacement in the U.S.

- Historical documents show she was a highly educated woman and well-respected in her community

- Parts of her story are hard to piece together, with little remaining of her own writing

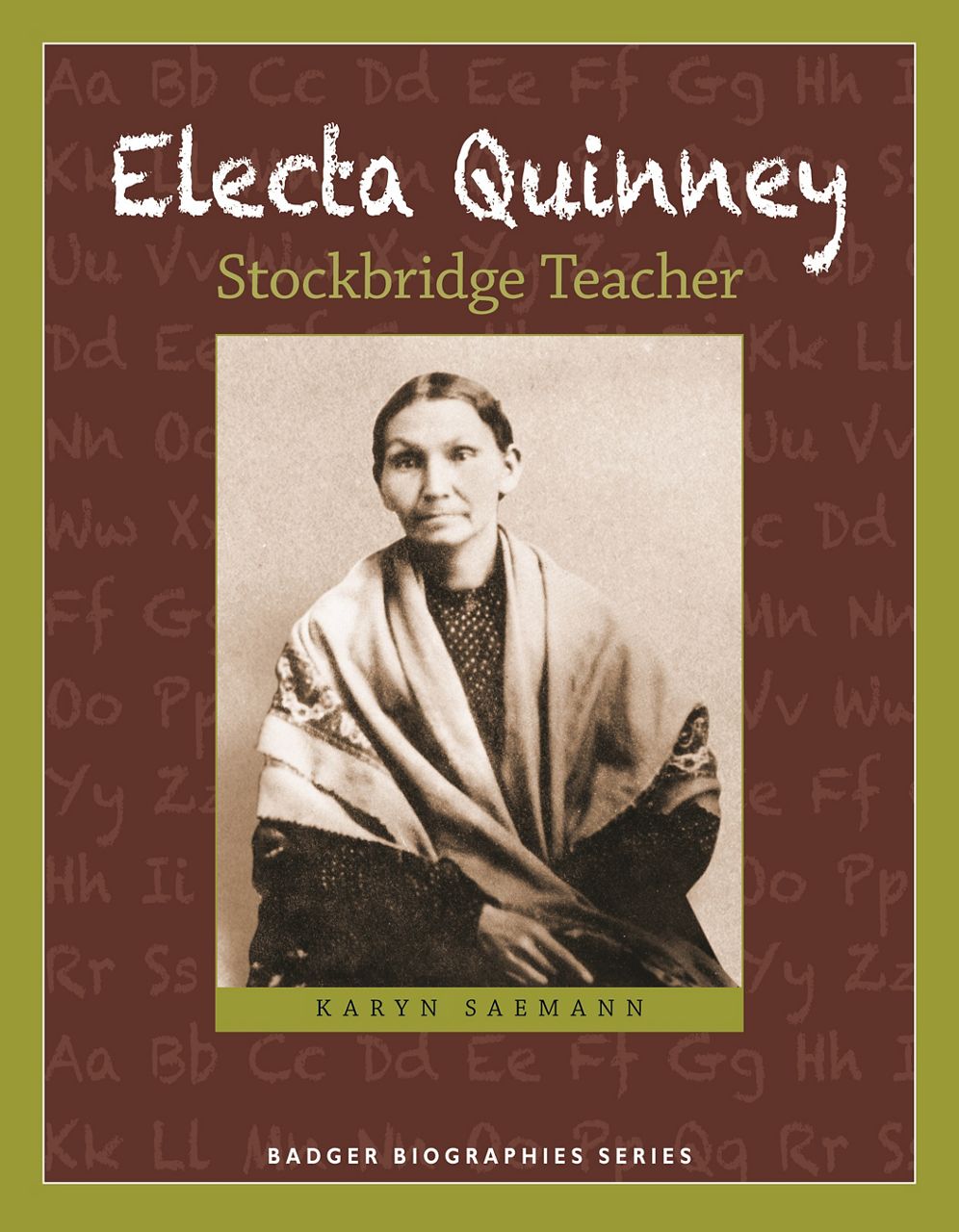

For Karyn Saemann, that was a story worth highlighting. Saemann, who works as a newspaper editor in southern Wisconsin, wrote a book about Quinney’s life for the Wisconsin Historical Society Press in 2014.

Quinney’s life isn’t just about being a historic “first.” It’s also a story of a fascinating woman, whose life intersects with many important threads of American history, Saemann said.

“It took so long for her story to be told, almost 200 years,” Saemann said. “I feel like she is still teaching, like her teaching isn't over, and I have this remarkable opportunity to help her.”

Ahead of her time

Though Quinney is now seen as a trailblazer for Wisconsin, her story took her across many parts of the young United States.

“She was born in New York in 1807,” Saemann said. “And she was born to a very prestigious family in the Stockbridge Nation.”

From early on, education was a key part of Quinney’s life. Coming from a well-connected family — her father and grandfather were both tribal leaders — she enrolled in a prestigious finishing school at age 7, “the kind of school that very wealthy white families sent their daughters to,” Saemann said.

She’d later spend time with a Quaker family to finish her education. By the time she was a young adult, Quinney was already teaching on Long Island.

But she wouldn’t be staying in New York for long. The early 1800s were a time of major change for the Stockbridge people — now known as the Stockbridge-Munsee Community Band of Mohican Indians.

Though they had spent more than 2,000 years living in the area, starting long before the United States existed, the Stockbridge found themselves under pressure from white settlers to leave their lands in New York.

“The state of New York wanted them out,” Saemann said. “They saw the writing on the wall.”

The group decided to set off for Wisconsin, where they had made an agreement with the Menominee tribe to settle on some of their lands. By June 1828, Quinney had landed in the town of Statesburg, on the Fox River, where the Stockbridge built a new community.

And soon enough, that community would quietly make history — starting the first-ever public school in the region, with Quinney as its teacher.

“The Indians as a community were paying her. It wasn't just the families of the kids who were going to her school,” Saemann said. “There’s no record before this of an entire community saying, ‘We need to have a school, so all together we’re going to pay the teacher.’”

Classes were held in a one-room schoolhouse in the woods, which also doubled as a church building. Quinney taught everything from math and reading to public speaking and geography, and started each day with a prayer, Saemann said.

While many of Quinney’s students were Native, she also taught white children in her school, including the kids of missionary Jesse Miner.

Miner himself wrote about Quinney in an 1828 letter cited in Saemann’s book, saying, “She is a person of good education. She is very faithful to the children.”

And his son Eliphalet, who wrote down his memories of Quinney’s classroom, described her as “a better teacher than the average of teachers,” noting that she “rarely whipped” the students — a contrast from many white families that still used corporal punishment in those days, Saemann explained.

It would take many more years for public school to become widespread in the region, she said, meaning that Quinney’s classroom was far ahead of the curve.

“This was an Indian community on the Fox River that was way ahead,” Saemann said. “Decades and decades ahead of everybody else here, in terms of having a public school.”

Living through history

It’s not a huge surprise that the Stockbridge people were paving the way on public schools, Saemann said. They had a long history of valuing education, including learning about the English language and Christian faith.

Even so, “adopting the white man's religion and education did not assure acceptance,” a Stockbridge-Munsee tribal history describes. “As long as Native people held land, they were subject to removal.”

And throughout her life, Quinney was often caught up in the crosscurrents of history — in a new nation that was at odds with those who had lived on the land for much longer.

“Had she lived 50 years before or 50 years later, she wouldn’t have been part of all of this really important history,” Saemann said.

In 1836, Quinney and her first husband, Daniel Adams, moved from Wisconsin to a home near the newly formed Indian Territory — a stretch of land in the Great Plains, where many Native people were forced to live in the wake of the Indian Removal Act. Adams, a Methodist missionary, was hoping to convert more Native people in the area to Christianity.

But Adams passed away in 1844 without much success in building a congregation. Soon after, Quinney married a man named John Walker Candy, an influential figure who helped run a bilingual newspaper in English and Cherokee.

This second marriage was another example of Quinney’s life of influence, Saemann said.

“She was always connected in really high places,” Saemann said. “She was not just a layperson in the Stockbridge Nation — she was the daughter of a tribal chief. She didn’t just go down to Indian Territory and marry a Cherokee Indian — she married the secretary of the Cherokee Nation.”

Eventually, Quinney headed back to Wisconsin in 1855 to see her brother, who had gotten sick. After he died, Quinney inherited the family farm and decided to stay — even after her husband chose to head back to Indian Territory.

Quinney faced some difficult times in those years, Saemann writes in her book. Her husband died after dealing with years of conflict within the Cherokee Nation. She also lost several of her children and stepchildren — including her son Daniel, who died of pneumonia while fighting for the Union in the Civil War.

Still, Saemann writes, Quinney was generous in supporting her close friends and family, even when she didn’t have much to share. And in 1882, Quinney passed away on her farm — after living through some formative and tumultuous chapters of Native American history.

A few weeks before she died, Quinney wrote that she was still of “sound mind, memory and understanding … Blessed be Almighty God for the same.”

Always a teacher

After Quinney’s death, it took a long time for her life to get its time in the spotlight, Saemann said. Part of the problem is that Wisconsin’s first teacher didn’t leave much of her own writing behind.

“Sadly, we don’t have a lot from her,” she said. “Some of that is because, as an Indian woman in the 1800s — and this is not unique to Electa Quinney — their stories weren’t deemed important enough to save or to write down.”

Even after years filled up with “a lot of driving around Wisconsin, and a lot of piecing together a million pieces of her life,” Saemann said much of what she was able to find about Quinney came from others who passed through her story.

Many of them seemed to hold Quinney in high regard. One person wrote that she moved in “the best society at Ft. Howard,” while another described her as “one of the most intelligent ladies I have seen for days.”

“As a mother and a teacher as a community member, she was so respected by everybody that came in contact with her,” Saemann said.

Stories about Quinney also show that she could comfortably step into white society, but still placed value in her Native culture, Saemann said. It’s said that she turned down a marriage proposal from Ebenezer Childs — a key figure in Wisconsin history — because she only wanted to marry an Indian man.

One key find that helped shed light on Quinney’s life was a trunk left behind by her son John, which was found in an Antigo barn decades after his death. The trunk contained many personal letters Quinney had saved, Saemann said.

The conversations here are one-sided: We only know what people were writing to Quinney, and not what she said in response, Saemann explained.

But poring over the letters still shed light on parts of Quinney’s life, she said — like her son writing sick from the Civil War battlefield to ask for her advice, or her friends apologizing to the well-educated Quinney for any spelling mistakes in their writing.

“When I got into the letters — all the big stack of letters that I was sitting with a magnifying glass and trying to decipher — it became really clear that her whole life, and even as she got older, that she was always a teacher,” Saemann said. “This was her identity.”