ANTIGO, Wis. — The bald eagle admitted to Raptor Education Group Inc. earlier this week was not looking his best.

A man had brought the bird to the wildlife rehabilitation center after picking it up near the Shawano area. He’d found the eagle sitting by the side of the road, too weak to move.

What You Need To Know

- A recent study found almost half of bald and golden eagles in the U.S. suffer from chronic lead poisoning

- Eagles can pick up fragments of hunters' lead bullets while scavenging for their food

- Loons and swans in Wisconsin can also get sick from ingesting lead fishing gear

- Wildlife rehabilitators encourage hunters and anglers to use non-lead alternatives like copper bullets

“Here he is — an eagle who's supposed to be the strong, powerful symbol of America — so debilitated he can't fly,” said Marge Gibson, co-founder and executive director of the center. “He can't take care of himself.”

Gibson and her team soon confirmed the eagle was suffering from lead poisoning — something that’s become a common sight for Wisconsin wildlife.

Lead has been an issue for the state’s birds for a long time, said Sean Strom, fish and wildlife toxicologist with the Wisconsin Department of Natural Resources. Often, eagles and other species will pick up pieces of the toxic metal left behind from bullets or fishing gear. And just like humans, they can face dire health consequences from lead exposure.

Now, researchers have confirmed that lead is taking a toll on eagles across the whole continent. A recent study of bald and golden eagles across the U.S. found that almost half of them suffered from chronic lead poisoning — and that lead was likely stunting population growth in these species.

For Gibson, the findings weren’t a surprise. She’s seen hundreds of firsthand cases of birds dealing with the toxic consequences of lead.

“I find myself apologizing to my patients all the time,” Gibson said. “They're intelligent beings. They're a symbol of America.”

We like to think of eagles as impressive hunters, swooping down to pick up fish, Gibson said. But it’s important to remember that they’re also scavengers: In the winter months, “what's accessible to them are things that are shot or dead or left in the woods,” she said.

Unfortunately for the birds, sometimes that means digging into the gut piles of carcasses left behind by hunters — and peppered with bits of lead ammunition.

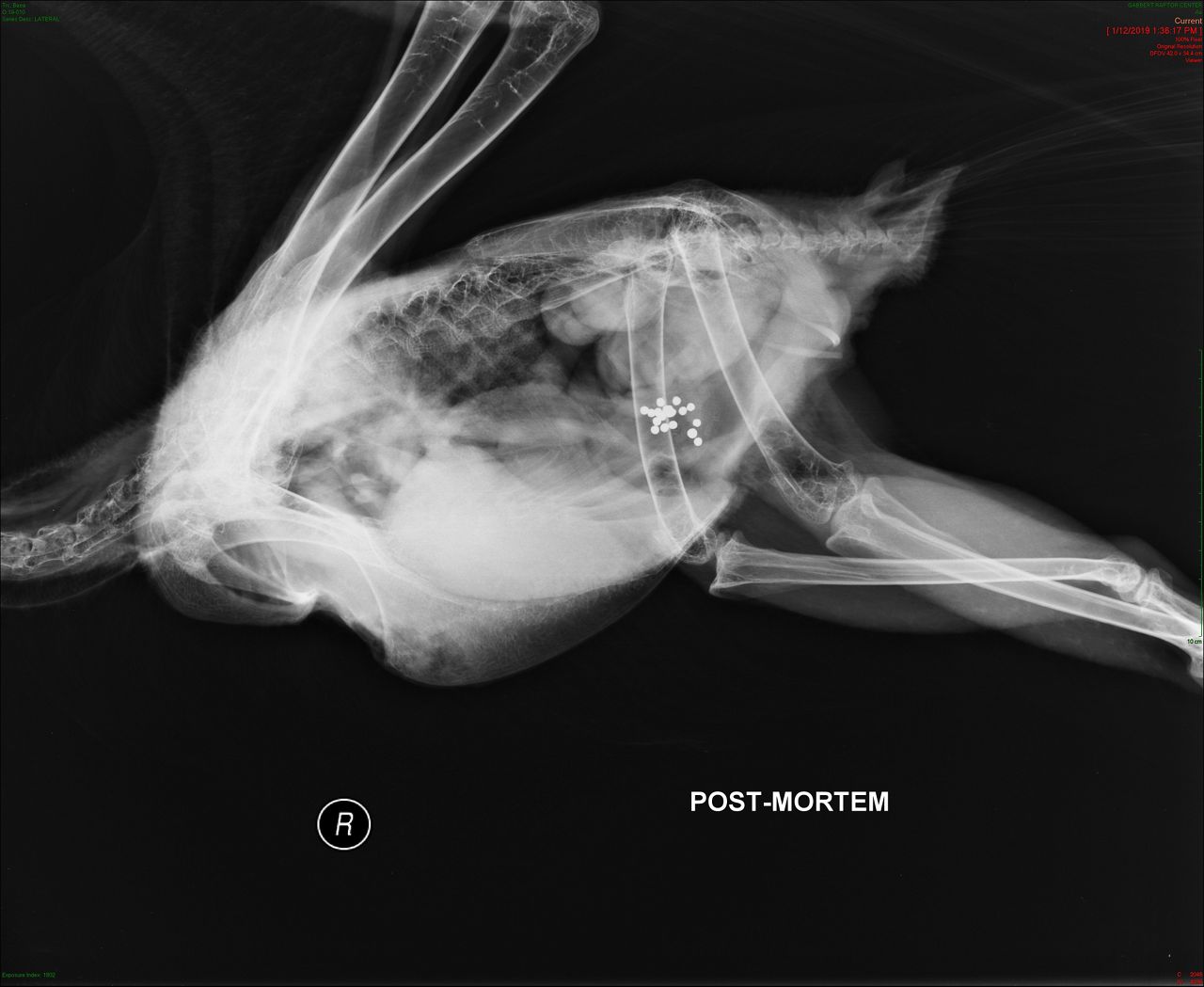

Lead bullets are still very popular for hunting game, Strom explained. And when those bullets hit their target, they fragment, spreading tiny pieces of the toxic metal throughout the body.

So as eagles are scavenging, they may be picking up pieces of ammunition along with their meal, said Vincent Slabe, a lead author on the recent eagle study. His team found that eagles are more likely to be lead poisoned during the winter, in line with hunting season.

“They're just eating, eating, eating,” said Slabe, a research wildlife biologist with Conservation Science Global. “And they're incidentally ingesting these chunks of lead.”

Eagles aren’t the only birds dealing with lead exposure in Wisconsin. In a DNR study from 2009, Strom and his team found that lead also poses a major threat for trumpeter swans and common loons.

With these species, other forms of lead may play a role, Strom said — including lead sinkers used for fishing. Loons, which like to swallow small stones to help their digestion, might pick up these lead weights by accident because they are around the same size, he said, or eat a fish that has been exposed.

And even though lead shot has been banned for hunting waterfowl since 1991, some leftovers can still be found buried deep in the mud. Swans, which dig deep into the sediment for their food, can end up bumping into these decades-old lead deposits, Strom said.

The DNR study found that for these three species — bald eagles, common loons and trumpeter swans — lead poisoning was behind 15 to 30% of deaths.

It doesn’t take much lead to cause health problems for these animals: A fragment smaller than a grain of rice is enough to kill an eagle, Slabe said. And once lead pieces get into the body, they tend to stick around, including by getting stored in the bones.

“With heavy metals, once they get into the system, they don't come out naturally,” said Mark Naniot, director of rehabilitation at Wild Instincts rehab center in Rhinelander. “So that's part of the problem. They could get a little bit of lead from a fish, a little bit of lead from a deer carcass, and that builds up in the system to the point where it becomes toxic.”

When lead gets into an eagle’s system, it takes a toll on just about every organ in the body, Naniot explained.

“They can't fly. They can't digest food,” Gibson said. “Often when they come in with lead poisoning, they're starving as well because their digestive system has been shut down. And then they go into organ failure.”

One of the telltale signs of a lead poisoned eagle is wing droop, where the raptors’ muscles get degraded to the point where they can’t hold up their wings, Slabe said. Green stains on the tail can mean that lead is blocking the digestive system from breaking down food properly, he added.

The eagles may also suffer from crop stasis — when a piece of lead gets stuck in the crop, the first stomach in the birds’ throat, blocking other food from moving through.

“So the bird is essentially starved to death, because it’s unable to move food from its first stomach down to the rest of its digestive system,” Slabe said.

And as a neurotoxin, lead can transform eagles’ behavior, Strom said, leaving the birds lethargic and unable to move. A lot of times, Naniot said he sees eagles having seizures from high lead levels.

Out of the 100 or so eagles Gibson sees at the rehab center each year, she estimates around 80% come in with lead poisoning.

At Wild Instincts, the numbers are similar: Naniot said around 80 to 90% of their admitted eagles have lead poisoning, and some of them come in with lead levels that are too high for their screening system to read.

“Just about every eagle that we see has some levels of lead in it,” Naniot said. “And so it is a real problem.”

Caring for a lead poisoned eagle is an intensive task, the rehabbers said. The first step is to flush the metal out of the bird’s system through a process called chelation — using chemical injections that bind to lead and carry it out of the body.

Naniot said this process is a bit like chemotherapy: It helps with recovery in the long run, but can also make an eagle sicker at first, leading to dehydration and depleting essential metals like copper and zinc.

So even once a bird is lead-free, it won’t be back to normal right away, the rehabbers said. It might take weeks to months of support — feeding, exercising, building back muscle — before an eagle is in good shape to head back into the wild.

“It’s a very difficult process,” Naniot said. “It can be long, and it can be expensive.”

Bald eagles have managed to make a major recovery in Wisconsin in recent decades. Their comeback has taken them off the endangered species list and made them much easier to spot in the state. And golden eagles — which don’t breed in Wisconsin but pass through the state in the winter — have stabilized as well.

“A lot of people think, ‘Well, if there's that many eagles out there, lead can't be that much of a problem,’” Naniot said. “But it's a lot more than what they realize. I always tell those folks that they've never had an eagle die in their hands from lead poisoning, and I've seen many cases of it.”

In fact, eagles could be bouncing back even faster if lead poisoning weren’t an issue, Slabe’s study estimates.

The researchers found that bald eagle populations — which are seeing an increase of about 10% per year in the U.S. — could be growing 4% faster without lead poisoning, Slabe said. And for golden eagles, whose numbers aren’t growing or shrinking, lead poisoning has been stunting growth by around 1%, the study found.

For a species on the brink, that 1% damper “could be the difference between a stable population and a declining population,” Slabe said.

So, even though eagles are generally doing well in Wisconsin, Strom said addressing lead still matters.

“These are human-caused deaths,” Strom said. “That problem can be fixed.”

In Wisconsin, there are some regulations on using lead for hunting, Strom explained. Lead shot is banned for hunting waterfowl, like it is across the country, and also banned for hunting doves on state lands.

Beyond those rules, Strom said the DNR has been working to encourage hunters and anglers across Wisconsin to switch over from lead products. Copper ammunition is an effective replacement for hunting deer, he said, and tungsten is becoming a popular alternative for fishing tackle.

These non-toxic alternatives do tend to be more expensive, Naniot acknowledged, and hunters may have to plan ahead to get their bullets in time for the season. Still, for him, “when you think about all the animals’ lives that you’re putting in jeopardy, it is well worth the price.”

Naniot said that while he’s seen some growing awareness of lead poisoning in wildlife, he’s also seen some pushback from people who think limiting lead is meant to prevent people from hunting or fishing. Gibson added that the rise of hunting with semiautomatic rifles has been another setback in recent years, since those weapons can leave much more lead in the landscape.

But researchers and rehabbers agreed that the goal isn’t to stop people from hunting altogether. After all, Slabe pointed out, hunters are a group of people who care deeply about animals, and have a strong history of being active in conservation efforts.

“We have a great history of hunting here in our state,” Gibson said. “I hunted, my grandchildren hunt, but there's ethics that go along with that. You know, do no harm.”

Gibson and Naniot agreed that it’s frustrating to keep treating birds for a condition that can be prevented by changing human behavior. But they’re hopeful that more people will come around to using non-toxic ammunition as they learn about the lead issue.

“We broke it, we should fix it, as humans. Because it's basically our fault that they're getting exposed to this lead out there,” Naniot said. “It’s because of the things that we've done in our hunting and fishing and different environmental practices. And so it's something that's fixable.”