MILWAUKEE — “SMILE!! You’ve got an impossible job!” the flier tells principals. “Remember, you’re doing it to make freedom possible in Milwaukee.”

The “impossible job” in question: Running an all-volunteer school to teach students about freedom, civil rights and Black history — all in the name of desegregating Milwaukee classrooms.

What You Need To Know

- In the 1960s, Milwaukee schools remained highly segregated, even in the wake of Brown v. Board decision

- Local leaders organized a series of school boycotts in protest and held their own Freedom Schools to keep kids learning

- The volunteer-led Freedom Schools focused on teaching students about Black history and civil rights

- The boycotts left a mark on the school desegregation movement, which was helped along by a federal lawsuit from Lloyd Barbee

These “Freedom Schools” were a big part of the effort to integrate Milwaukee’s public schools in the 1960s. Frustrated with the system’s continued racial divides, local leaders organized a series of boycotts, pulling thousands of students out of school and sending them to community-led classrooms instead.

The Freedom School boycotts played a key role in highlighting the discrimination against Black students, said Clayborn Benson, director of the Wisconsin Black Historical Society.

“It shook the core of the whole school system,” Benson said. “To defy the law — and that was the law at that time — the powers to be thought it was a major violation.”

And along the way, organizers hoped to impart some essential lessons to a generation growing up in the midst of the civil rights battle.

“Remember: Schools exist for students,” organizers wrote in a guide for volunteer teachers. “We can give Freedom School students a day to remember, a day that will be a new beginning for them and for us.”

‘Cheating on Brown’

In 1954, the Supreme Court made the call: Segregation in schools had to end.

The previous case of Plessy v. Ferguson had established the idea of “separate but equal” — that schools could be segregated as long as their quality was the same. But in Brown v. Board of Education, the court ruled that segregated schools are “inherently unequal,” and that classrooms across the U.S. would have to integrate.

Desegregating schools was easier said than done, though, said Robert Baker, an instructor in UW-Milwaukee’s Department of African and African Diaspora Studies.

“Milwaukee Public Schools was really hesitant on changing the segregation patterns,” Baker said. “And they pointed to the city's overall segregation and said, ‘Hey, look, it's not our fault our schools are segregated, Milwaukee’s segregated.’”

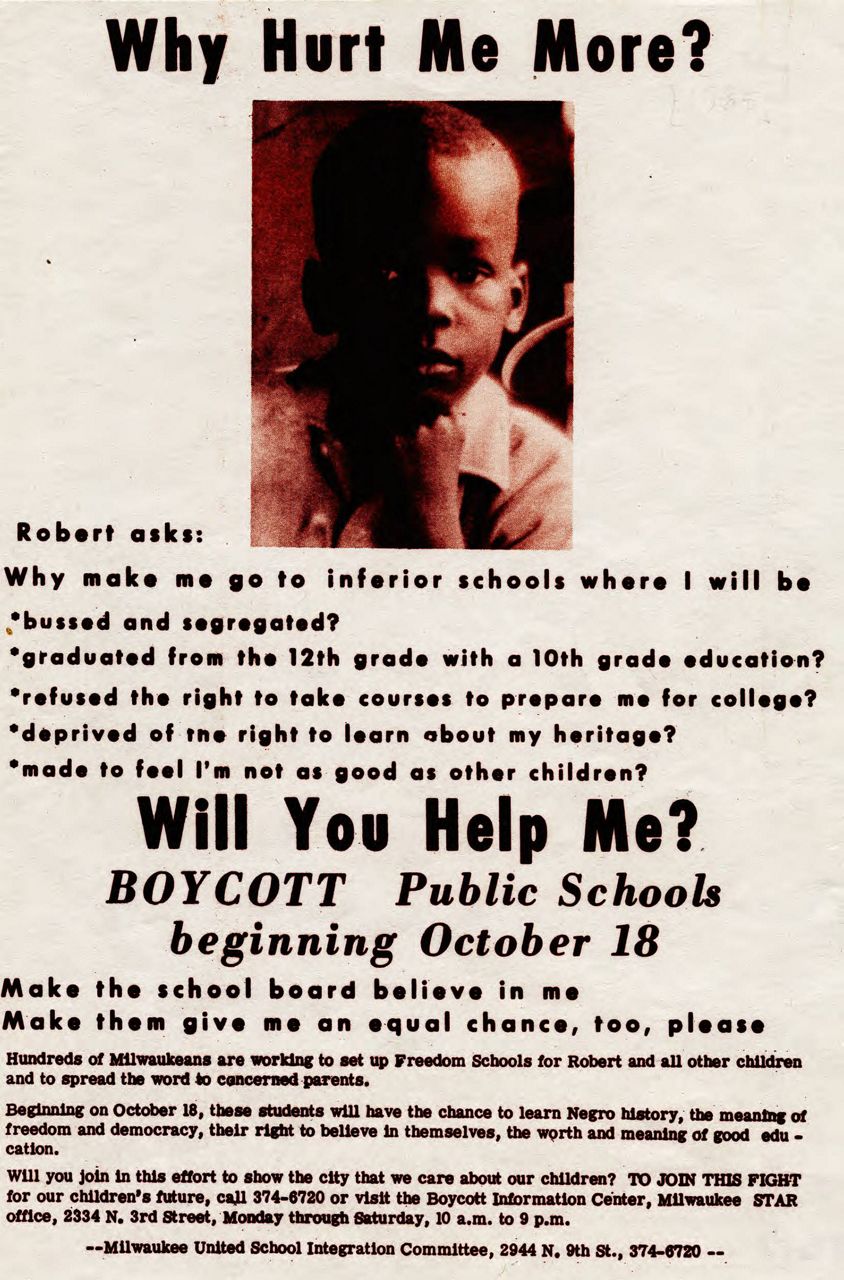

Milwaukee, like other cities across the north, continued “cheating on Brown,” Benson said — including through the process of intact bussing, where Black students would be brought into primarily white schools, but still kept separate. School boundaries were drawn in ways that reinforced housing segregation, instead of working against it, community leaders argued.

So, even a decade after the Supreme Court case, the city’s classrooms remained highly segregated. A statewide report at the time found that in the school year between 1964 and 1965, most Black students in Milwaukee attended schools that were at least 95% “nonwhite.”

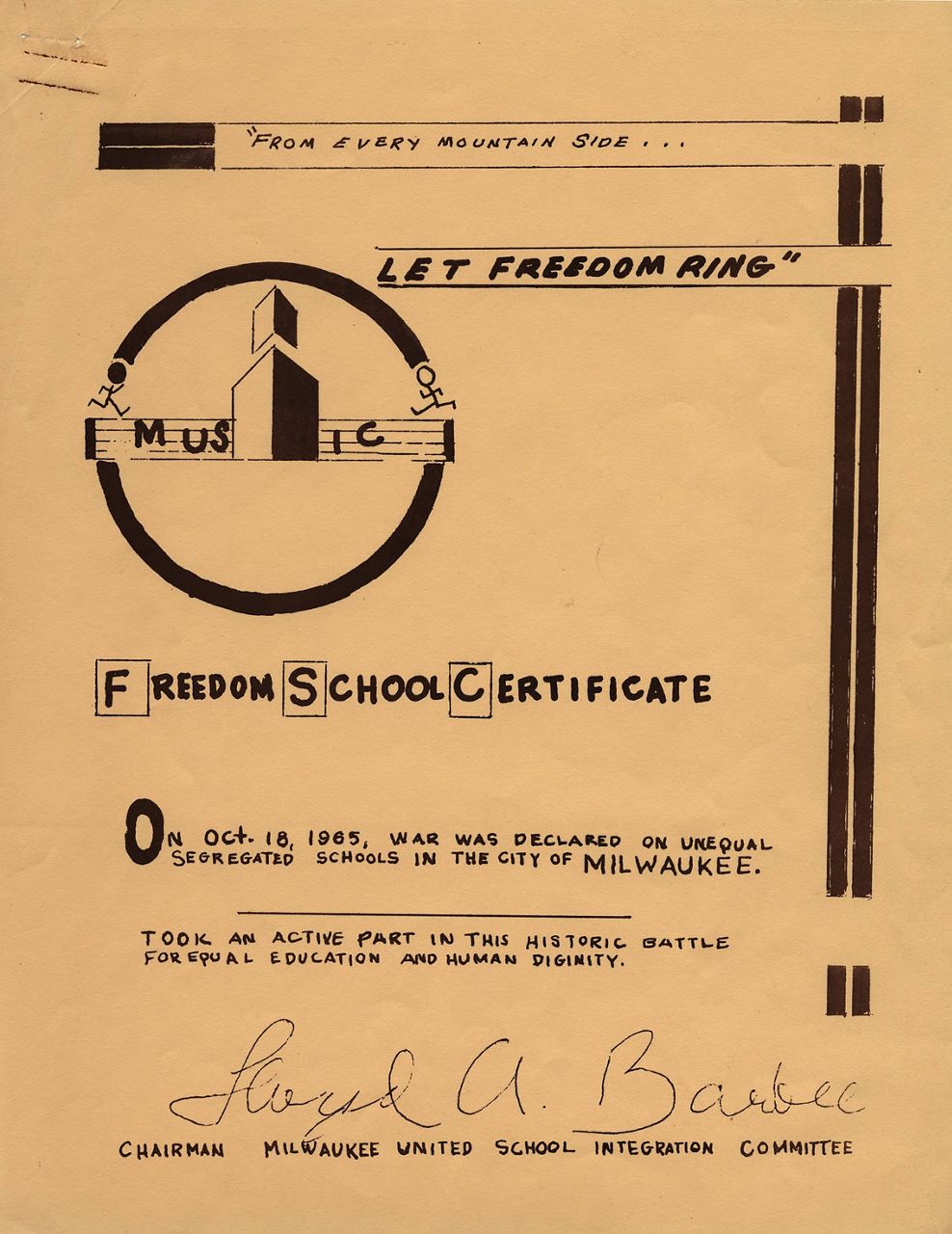

Milwaukeeans decided to take action. Civil rights leader Lloyd Barbee, along with other community leaders, came together in 1964 to create MUSIC — the Milwaukee United School Integration Committee — and put pressure on the school board to truly desegregate.

“Milwaukee operates Negro schools and white schools as a matter of day to day practice,” Barbee wrote in a 1965 letter. “Such racial segregation in public education, regardless of its cause, is discrimination and must be eliminated.”

The issue wasn’t just that many schools were primarily of one race — although that was an issue, leaders argued, since segregation “prevents children of both races from getting to know each other as human beings and fellow Americans” and “preserves racial fears and hatreds.”

But even beyond that, primarily Black schools were not seen to have the same resources as mostly white ones, said Dave Driscoll, curator of economic history at the Wisconsin Historical Society.

Black students were being left with inadequate supplies and underqualified teachers, Benson said — even as many Black families had migrated north in part to make sure their kids could get a real education.

“Lloyd Barbee and others were trying to change that. Get the school district to basically do better by their Black students,” Driscoll said. “And they weren't making a lot of progress, and that prompted the boycotts.”

Community classrooms

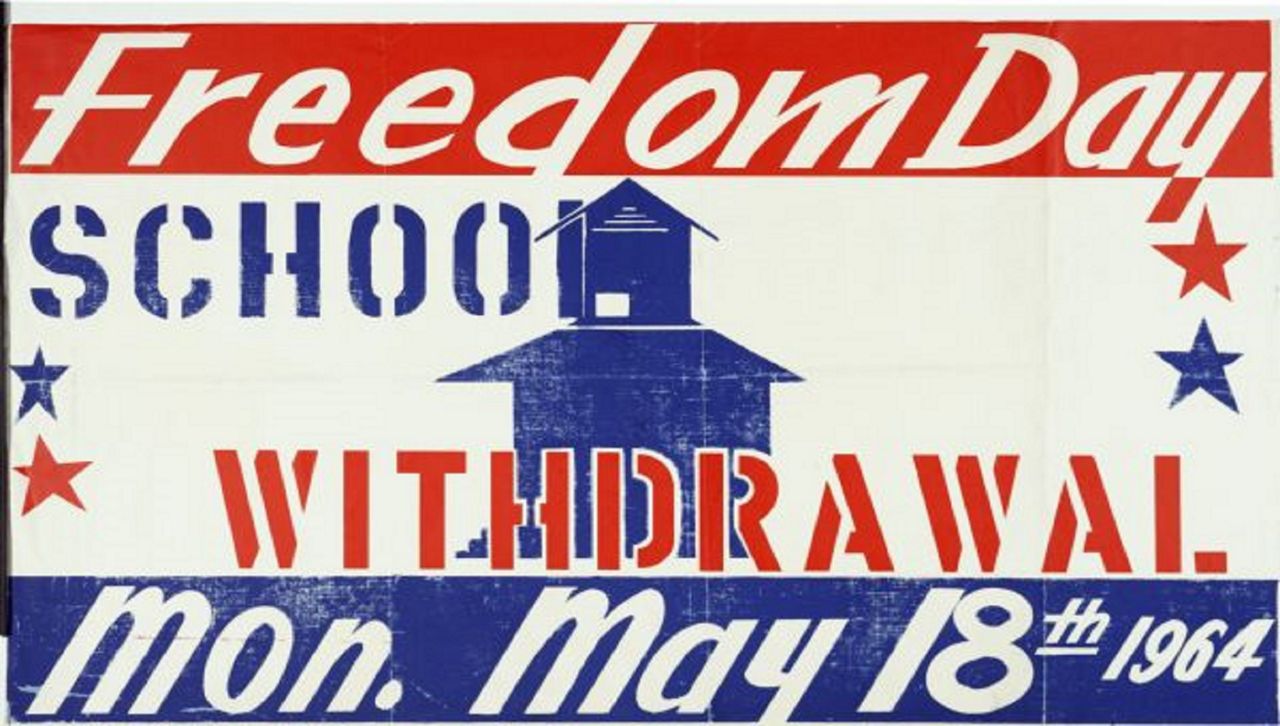

So, on May 18, 1964 — one decade and one day after Brown v. Board first passed — thousands of children in Milwaukee went to school, just not the school they were assigned.

MUSIC had convinced parents across the district to keep their kids out of public schools to bring attention to the segregation issue, Benson said. During this first boycott, around 11,500 students stayed out of their normal classrooms, he said.

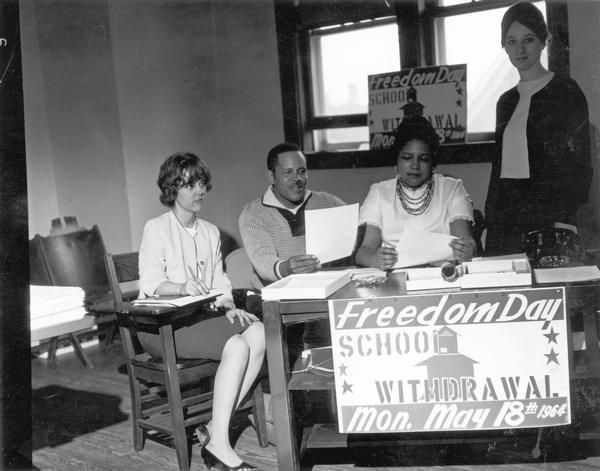

But for boycotting students, this wasn’t a day off. Instead, many of them headed to local churches and centers for Freedom Schools run by parents, organizers and other community members.

“They wanted to bring a message to the school system that they're still going to learn, but they're going to learn under our control,” Benson said.

MUSIC ended up holding three major school boycotts over the course of three years. And each time, the Freedom Schools offered their own teachings on four main concepts: “Freedom, justice, brotherhood and equality.”

At the time, there was a big push for Black people to learn more about Black history, Baker said. The various Freedom School sites were named after icons like Martin Luther King, Crispus Attucks and James Baldwin; lessons highlighted stories from Black heroes and civil rights activists.

Schedules for the Freedom Schools show that the classes took a hands-on approach to learning, with plenty of room for creative expression.

Elementary schoolers drew pictures of Black heroes and created plays to act out different types of freedoms. Older students wrote essays about their future goals and heard from a panel of local civil rights leaders. Schools held dance-offs and shared Freedom Songs (“We’re gonna shake up all Milwaukee,” the lyrics to one song declare).

And once classes got out, young people had the chance to put their new civil rights lessons to the test: “Encourage students to picket at the School Board after school each afternoon,” the principals’ instructions advise. “Offer them rides to do this if you are sure that they have their parents’ permission.”

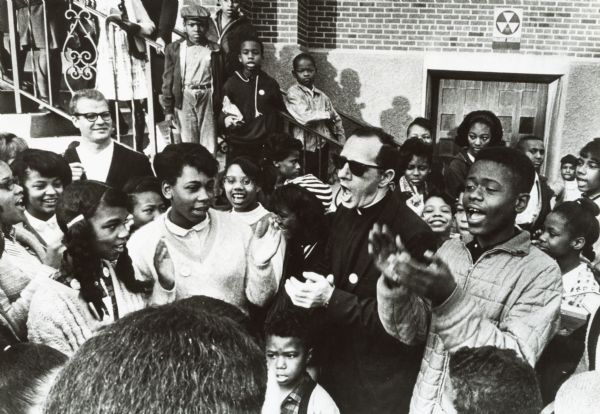

Throughout the neighborhoods, an impressive range of people mobilized to make the Freedom Schools happen, Baker said.

Parents volunteered as crossing guards and chauffeurs. Students at Marquette and UW-Milwaukee volunteered as instructors. Even groundbreaking alderwoman Vel Phillips pitched in to teach.

“It was a really important act of solidarity, which saw people from all across Milwaukee’s Black community getting engaged,” Baker said.

Taking to the courts

In 1966, MUSIC held its last Freedom School boycott.

Through the boycott efforts, Benson said, the organization was able to deliver a key message to the city: “Our kids are important. They’re the one most important thing that we have, and we have a responsibility to educate them, and you’re still discriminating against them.”

But reaching MUSIC’s goal of a desegregated school system would take some more time — and a different kind of action. Even after the boycotts and other direct actions from local leaders, the school board was slow to make a change, Baker said.

Barbee decided to turn to the courts, where he saw many Black people securing their rights, Baker said. He filed a federal lawsuit against the board, claiming that they were unconstitutionally keeping schools segregated.

In 1976, a decade after the Freedom School efforts came to a close, a federal judge agreed with him.

“Sometimes, change doesn’t happen overnight,” Baker said. “As much as we want to flip a switch, and for our bad history to be erased, the reality of it is it takes time to change the hearts, minds and culture of a city.”

Even though it took some time, Baker said it’s important to recognize how drastically things have changed in the wake of the MUSIC boycotts.

The ruling in Barbee’s case created a “direct line” to future school choice programs in the city, Baker said. Milwaukee Public Schools would go on to create magnet schools to attract a mix of students, and would also open up student transfers between suburban and city districts with Chapter 220.

For Driscoll, the boycotts are part of a civil rights story that is important to tell across the state. The Wisconsin Historical Society recently brought five desks into its collection that were used at one of the original Freedom Schools — with the hope that they might help give people a way into this history.

“Everyone, certainly of my age, sat in a desk exactly like this at some point or another,” Driscoll said. “That makes it easier for a lot of people to absorb history, if you can be mentally transported to a place.”

And Baker, who himself has been active in racial and social justice movements, said there’s a lot of inspiration in the Freedom School efforts — from the intergenerational team-up between the city’s elders and its youngest residents, to the way it brought a huge swath of the community together.

“I do believe that Milwaukee has always been at the vanguard of justice and social change, and we oftentimes don't get the credit,” Baker said. “The record speaks for itself. And so, we have a lot to be proud of.”