GRAFTON, Wis. — In the small village of Grafton, on the side of a grassy hill that slopes down to the Milwaukee River, a bright blue sign marks the spot.

It’s the site where some of the country’s most important blues voices once flocked from all across the country to record their music — the former factory and recording studio of Paramount Records.

What You Need To Know

- At the turn of the 20th century, the Wisconsin Chair Company started making records to help sell its phonograph cabinets

- Paramount Records became one of the most influential producers of blues music in the U.S.

- Artists like Ma Rainey, Louis Armstrong and Charley Patton recorded music in Grafton — but many weren't paid for their work

- Some are still fighting for Black artists to get more recognition for their role in this local history

The buildings have long been torn down, but Paramount’s legacy lives on. The music it captured from some of the great Black artists of the 1900s would form the basis for generations of American culture.

“I don't know how to convey in words the magnitude of this history,” said Angie Mack, a Grafton-based music teacher and local blues historian.

And it all started from an unexpected place: In a highly segregated Wisconsin town, when a chair company decided it would try its luck in the record industry.

“There's this really important, fundamental piece of Black Wisconsin history, of Black American history, right here, in small-town Grafton,” said Sergio Gonzalez, an assistant professor at Marquette University. “We often find these stories in places that we didn't think they would be. But in many ways, it's impossible to talk about Port Washington and Grafton without talking about Paramount.”

Building the blues

In the beginning, the Wisconsin Chair Company “did exactly what its name says,” Gonzalez explained: It made chairs.

After it was founded in the 1880s, the Port Washington-based company grew into one of the main economic drivers in the area, Gonzalez said. At its peak, the company employed one out of every six workers in Ozaukee County.

Around the turn of the century, the Wisconsin Chair Company started adding other types of furniture to its lineup — including phonograph cabinets that were designed to hold record players.

“Pretty quickly the company realized that they could sell more cabinets if they could also include music,” Gonzalez said. “And so, it began to branch out into the actual record-making industry.”

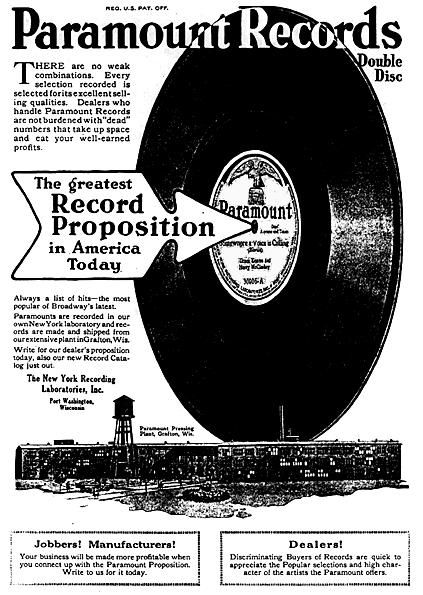

That marketing scheme led the company to dive into the music business with its very own label: Paramount Records.

The records were designed as a bonus that customers would get along with their cabinets, Gonzalez explained, like a free prize in a box of cereal. At first, these mostly were made up of “ethnic music” — records for specific immigrant groups, including German and Scandinavian songs.

But Paramount really hit gold when it turned its attention to a different genre: Blues music, or “race records” as they were called at the time, Gonzalez said. As the Great Migration was bringing many Black residents to cities in the north, like Chicago and New York, it was opening up a new market for record sales.

“The people who were buying these were the people who were arriving in urban spaces,” Gonzalez said. “People who had a little bit of disposable income, because they were now working in industrial jobs and made more money than they would have been in the agricultural south.”

Paramount started out pressing records that were captured in studios in New York. But by 1929, the company set up its own recording studio in Grafton, in an “old, barn-like building” attached to the factory, Mack said.

With the help of J. Mayo Williams, a Chicago newspaper man who was brought on as a talent scout, Paramount Records would go on to bring some of the greatest blues artists of the time into the studio. Kevin Ramsey, an actor and artist who wrote a musical about Paramount Records, said the range of brilliant artists really struck him while he was researching for the show.

"This all-white, German Scandinavian town furniture company, it's producing blues records," Ramsey said. "But it just wasn't any blues artists they were producing. They were producing some of the great trailblazers of American sound."

From Louis Armstrong to Ethel Waters, Ma Rainey to Charley Patton — the “Father of the Delta Blues” — dozens of artists across the country made their way up to Grafton to record their music. One of the label’s big stars was Blind Lemon Jefferson, a blind guitarist with his own haunting style, Gonzalez said.

Some of the names, like Skip James and Son House, might not be as widely known, Ramsey said. But these unsung heroes were all some of "the founding fathers, founding mothers, of this American sound," he said.

Paramount’s history “throws a wrench in our understanding of what Wisconsin music is all about,” Gonzalez said. It’s not just polka, Steve Miller and Bon Iver, but also some of the fundamental music of Black America.

The 1,600 or so records captured at the Grafton studio were key to the blues genre, Mack said. And the blues, in turn, would be the foundation for a huge range of American music — from rock to R&B to jazz to hip hop.

“This history shaped American culture,” Mack said. “We have pop culture because of this, and the artists that recorded here.”

A complicated legacy

Soon enough, Paramount had grown into one of the most important producers of blues records in the country, Gonzalez said. But its heyday couldn’t last forever.

The Great Depression hit the music industry hard, and Paramount was no exception. By 1935, the company shuttered its Grafton studio — leaving us with another great “what if” of history, Gonzalez said.

“You think about Motown being one of the most important producers for American music, for Black music, in the 20th century,” Gonzalez said. “Grafton never really had the opportunity to achieve that status, because of the Great Depression.”

In its time at the top of the music business, Paramount was able to leave a legacy of music from some of the most important blues artists in the U.S. Its legacy, though, is also tied up with some painful parts of Wisconsin’s Black history.

For one, even as Black musicians were invited to record their music in Grafton, they weren’t welcomed as residents, or even guests in the mostly white village, Gonzalez said. Paramount’s Black artists would often head back to Milwaukee after their studio time, since it was a safer place for them to stay.

“It speaks to the really complicated history that Wisconsin has with questions of race,” Gonzalez said. “Wisconsin has not always been the most welcoming state for communities of color. But it certainly has invited communities of color into the state for their economic necessity.”

And even as blues records were bringing in big profits for the company, the artists themselves weren’t getting rich off of them, explained Pearl Ramsey, a performing artist and niece of Kevin Ramsey.

The vast majority of Paramount’s Black musicians never received royalties for their work, Gonzalez said. Fiilzen’s article details how some contracts would promise the artists one cent for every “net” record sale after expenses — but would tack on so many costs that the musicians would end up with nothing.

“They employed the people that live in this city, and created much of the wealth here,” Ramsey said. “But they didn't receive the royalties, and many of them died without the royalties that they created for the company.”

Blues music wouldn’t have been popular among the white Wisconsinites who ran the company, Mack said. Instead, the records were being marketed to largely Black customers — shipped to Chicago by mail order, or sold out of department stores in the south, as Sarah Filzen writes in the Wisconsin Magazine of History.

The cultural differences between Paramount’s workers and its musicians might help explain why few artifacts remain from the studio, Mack said.

Many of the original masters from Paramount’s sessions have been lost over the years, Gonzalez said. Records from the studio have become rare collector’s items.

In part, this might be because the records were cheaply produced to maximize profits, he said. But there also wasn’t much effort to preserve the history after the factory closed: Filzen’s article describes how metal masters were sold to a junk dealer for copper scraps, and how Paramount workers “used the leftover record inventory for target practice, like clay pigeons.”

“They were taking the records and just tossing them out,” Mack said. “They had no idea what these names meant. But they knew that these songs are what gave them their livelihood.”

‘It’s bigger than Wisconsin’

When Mack first learned that there had been a major record label based in her city, it came as a shock.

“I didn’t believe it was true,” Mack said. “I had never heard anything about a recording studio in Grafton, and I had lived here for some years.”

Mack said she first encountered Paramount when she got a flier in her mailbox from a record collector, who was visiting Grafton to see if anyone had records to sell. At the time, she said, there wasn’t much information out there about the history-making blues label.

Since she started digging into it more than 15 years ago, Mack has been inspired to bring more attention to the Paramount story.

“I'm looking for truth. I’m looking for justice,” she said. “I’m angry that this history has been glossed over for so long.”

That work has included pushing for the creation of Grafton’s downtown Paramount Plaza, which since 2006 has stood as a reminder of the city’s blues history. The plaza’s Walk of Fame — designed to look like a giant piano — recognizes some of the great talents who recorded with Paramount, like Henry Townsend, Jelly Roll Morton and Thomas A. Dorsey.

Even beyond Grafton, Gonzalez said he’s seen some growing interest in this history in recent years. Rock star Jack White, who has family ties to the Paramount factory, released an extensive boxed set of the label’s classic tracks in 2013 and digitized hundreds of songs from the studio.

Kevin Ramsey said he's hopeful that his musical, "Chasin' Dem Blues," can help engage audiences with this history and the music that is "such a powerful influence in all of our lives" — and acknowledge the contributions of artists who haven't always been recognized.

"So many African American performers in that day, and even in the continuing industry, have been ripped off," Ramsey said. "Their sounds, what they've created, was stolen."

Still, Mack thinks there’s a long way to go in highlighting this piece of Grafton history — and in recognizing the label’s Black musicians, whose work helped build the city and found generations of American music.

Mack said she’d like to see a museum dedicated to Paramount Records in the city, and hopes that schools will include blues history in their curriculum. Blues music shows up “in every fiber of American culture,” she said — so it’s only fair to make sure these artists get their due.

“It’s bigger than Grafton, and it’s bigger than Wisconsin,” Mack said. “This history has international appeal. And it has influenced culture ever since the needle hit the wax.”

)