MADISON, Wis. — Sterling Martin has long had a passion for science. But he hasn’t always been able to talk to his family about it. He just couldn’t find the words.

Martin — now a biophysics graduate student at UW-Madison — grew up in Shiprock, New Mexico, a part of the Navajo reservation. His family mainly spoke Diné Bizaad, the traditional Navajo language.

Historically, the Diné language doesn’t have direct translations for a lot of scientific terms, Martin explained. That gap became clear when he’d try to explain to his family what he was learning about in college and get stuck with English words that didn’t cross over well.

“I could always just see that they weren’t really understanding. And it always felt weird and bad, because I want to share what I’m doing,” Martin said. “And I realized that this was kind of a nationwide problem.”

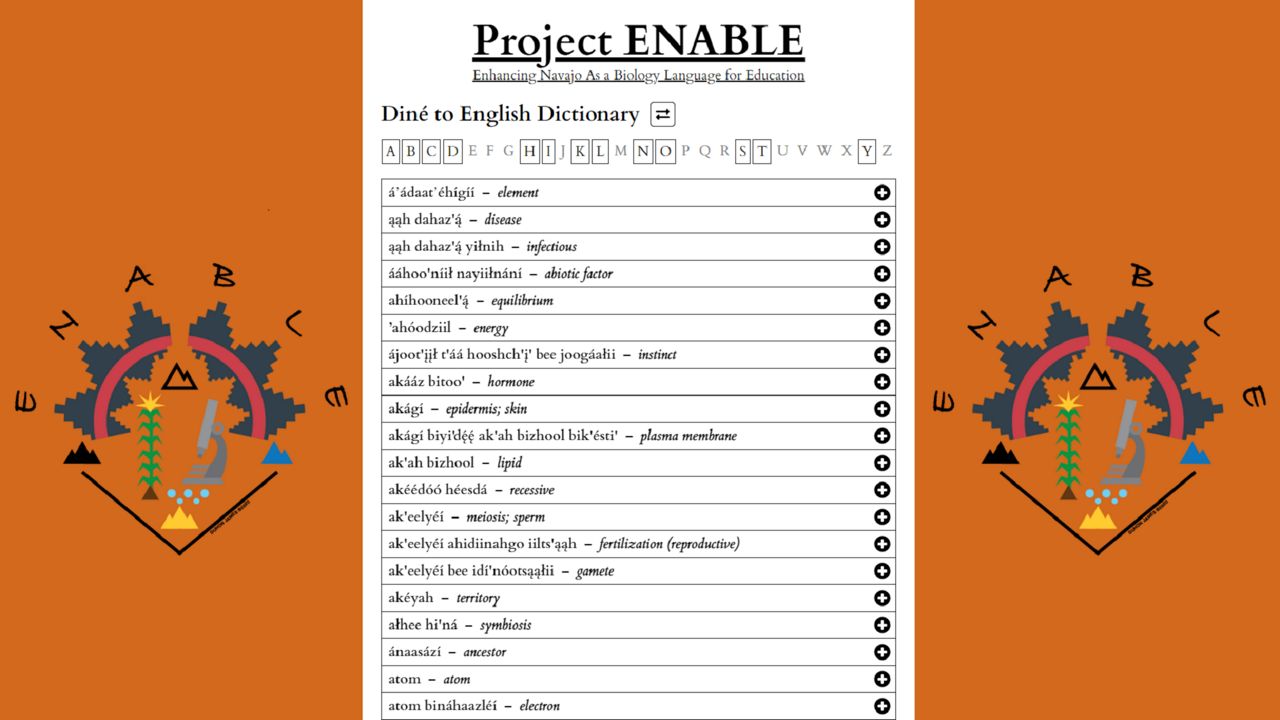

To break down some of those barriers, Martin teamed up with other scientists and language experts to create Project ENABLE, which stands for “Enhancing Navajo As a Biology Language for Education.” The effort focuses on creating new Diné words to describe biology concepts, as a way to preserve the endangered language and open doors for better communication about science.

The Project ENABLE team launched their online dictionary last month, offering Diné translations for around 250 biology terms — from “abiotic factor” to “zygote.”

For Martin, the project has already made a big difference. Talking with his family members — including some who have helped give feedback on the translations — he said he’s already seen a “huge change” in how they understand modern biology.

“I really can't explain how amazing it is to be able to talk to my mom and grandma, who Navajo was their first language,” Martin said. “Explaining these words, and being able to just have that conversation.”

Finding the right words

Creating hundreds of brand-new words didn’t happen overnight. Since the project first kicked off in 2019, it’s been a “slow and steady” process, said Susana Wadgymar, a Project ENABLE co-founder and assistant professor of biology at Davidson College.

“It’s been a labor of love,” Wadgymar said.

The team chose to focus on biology terms at the middle-school level, explained Joanna Bundus, another co-founder. That’s around the time when science learning moves from simple, straightforward words to more technical language, said Bundus, who joined the project as a former postdoctoral fellow at UW-Madison.

The word list was created with the help of biology teachers on the Navajo reservation, Bundus said. Throughout the process, “we wanted to get the expertise of people on the Navajo reservation who would actually be using the words the most,” she added.

After coming up with their list, the Project ENABLE members broke down the biology terms into accessible definitions in English, Martin explained. They then handed over these simplified definitions to their Diné linguist, Frank Morgan, an expert translator who grew up speaking Navajo as his first language.

“He’s a very traditional person, so when he makes these words, he comes at it from the aspect of the Navajo perspective,” Martin said.

For many of the terms, that means bringing together existing Navajo words to create meaning in new ways — sometimes through a mental image or action, Wadgymar said.

Martin pointed to the term “DNA” as an example. Instead of trying to figure out some direct translation for “deoxyribonucleic acid” — which might not end up having much meaning for Navajo speakers — Morgan built out a word that literally means “strands of life,” which gives a better sense of the molecules’ purpose and their double helix shape.

The terms in Project ENABLE’s dictionary build off each other, too. The translation for “chromosome” (iiná bitł'óól bit'oh) literally means “nest of DNA,” Bundus explained — conveying a mental picture of many strands of life tangled up together.

The word for “bacteria,” which translates to “bug you can’t see,” gets folded into the one for “antibiotic”: Ch'osh doo yit'íinii bee naatseedí, or “kill the bug you can’t see.”

Through all of this, Martin said it was important to have an expert who could navigate the ins and outs of the Navajo language — like a sentence structure that’s much different from English and the way speaking with distinct tones can change the meaning of a word. (One Diné word can translate to “beaver” or “poop,” depending on the tone, he said.)

And knowing the cultural context, including what words and topics would be taboo to use, was also key for the translation process.

“Sacred animals, things that have spiritual meanings, we’re very careful not to use those,” Martin said. “It can be very off-putting for traditional people.”

Sharing science, saving language

After years of work, it’s been a “game changer” for the team to finally have their translations available for Navajo speakers to use, Wadgymar said.

The website is specifically designed for easy access on the reservation, where internet service can be spotty, Bundus said. Project ENABLE’s web developer, Ira Fich, built out a site that doesn’t use too much data and won’t have to be reloaded every time someone wants to check a new word, she said.

The team is still working to flesh out the dictionary with example sentences in the Diné language and illustrations of biology concepts, Bundus said.

And they’d like to keep expanding their word list, Wadgymar said, especially focusing on medicine and the environment. Both of these topics have a disproportionate impact on Native communities, she said, like with the heavy toll of COVID-19 on tribes and the risks of climate change for indigenous lands.

Wadgymar said she hopes the Navajo community will benefit from having more access to the English-dominated field of modern science — in a way that can still incorporate their cultural background.

“I'm an educator and I think about accessibility to knowledge, and how disproportionate that is across different communities,” Wadgymar said. “Indigenous communities in specific have not had enough outreach and enough investment. So anything that we can do to help on that front is greatly needed.”

Breaking down these communication barriers has benefits for the wider scientific world too, she said, creating more common ground for different communities to learn from each other.

For Martin, preserving the Navajo language itself is another important, and personal, piece of the work. Like many other endangered Native languages, Diné bizaad has seen its number of speakers drop significantly in recent decades.

“A lot of my generation doesn’t really speak Navajo anymore,” Martin said.

By helping modernize the language with new scientific words, he hopes Project ENABLE can help carry Diné bizaad forward for new generations and get more Navajo people working in STEM subjects.

After spending time away from home for his studies, Martin said he started losing some of his own fluency with the Navajo language. But working on the project, he’s been able to reconnect — and has already seen the joy on his family’s faces when they hear the new words they’ve created.

“I’ve been out here for so long, and I’ve always wanted to find a way to give back,” Martin said. “It's been really hard being so far away. And I feel like this is the one little thing I can do.”

To see the whole list of translations, check out the Project ENABLE website.