Anne Van Herynen is an Appleton resident who grew up in Zevenaar, Holland, near the German border. World War II broke out during her formative years, and following is the third of a three-part series of how a young, teenage girl lived through the tragedies and triumphs of one of the most significant periods in our history. Read parts one and two.

APPLETON, Wis.— Anne Van Herwynen’s life growing up in Holland during WWII seemed to be a living nightmare.

Loss of freedom of speech, loss of freedom to go as you please, destruction and death.

And then the German SS (Schutzstaffel) Soldiers came to her home town of Zevenaar.

They not only came to town, they went to the homes of local residents and demanded they give up a room in their home so they could take up residence.

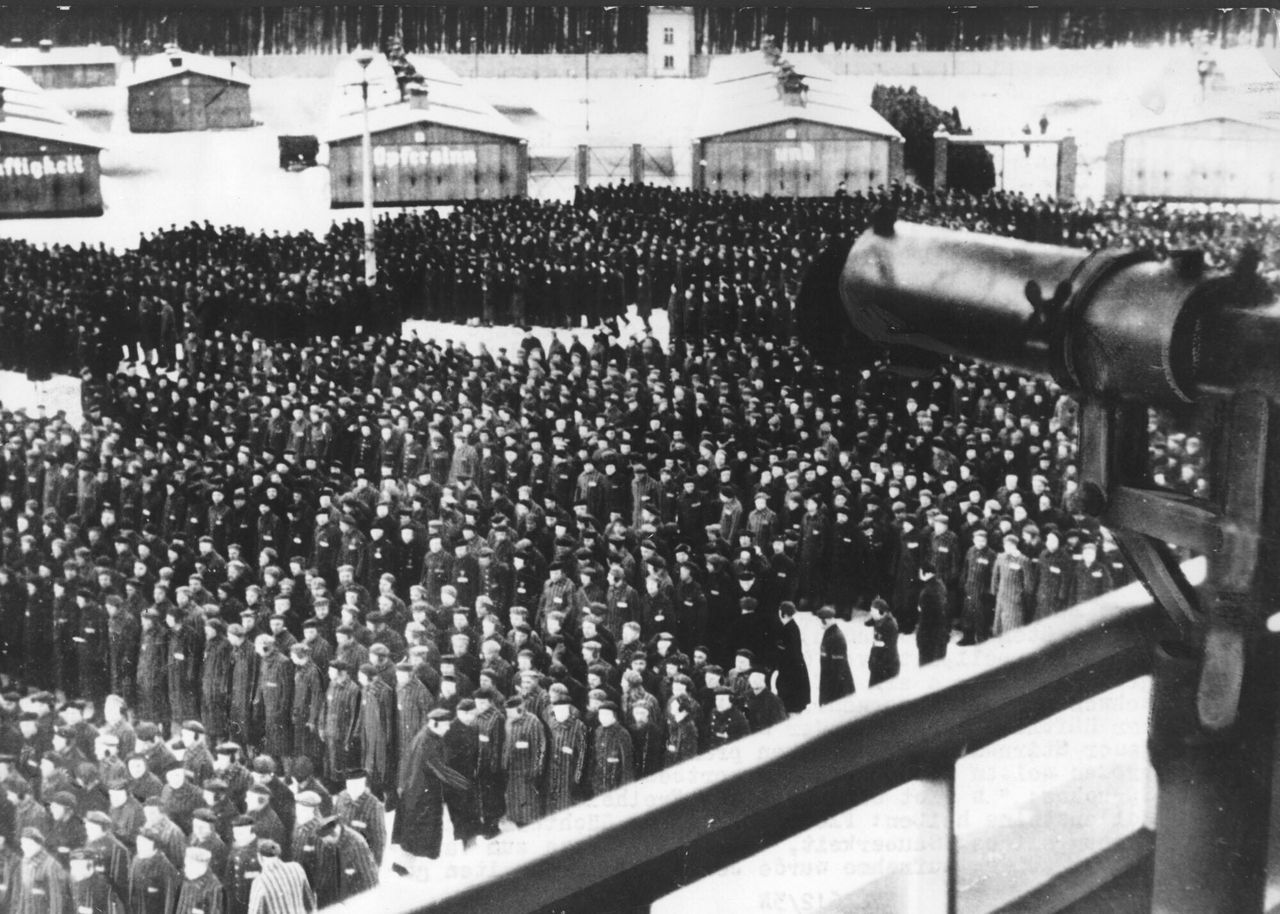

These were originally Hitler’s personal bodyguard unit that eventually became the elite guard of the Nazi Reich, specifically charged with the capture and murder of European Jews. Ruthless only begins to describe their existence.

“The SS, they were something else,’’ Van Herwynen said. “The bad ones. The black uniforms. We had to take the SS into our house. Can you imagine that?’’

When they came to the Van Herwynen’s home, there was immediate conflict.

Van Herwynen’s grandmother gave the SS their bedroom because it had an outside door.

“She said, ‘You don’t have to bother us,’’’ said Van Herwynen. “And I thought, ‘Here we go again.’

“Anyhow, he’s looking over the room. He’s looking over the bed and we had a picture in there of Queen Wilhelmina, and he took a look at that picture and said, ‘That picture has to come down.’ ‘No,’ she said. ‘That picture is going to stay here.’ He looked at her again and said, ‘That picture is going to come down.’ ‘No,’ she said. ‘That picture is going to stay there.’ And I thought, ‘Grandma, you’re asking for it.’’’

Grandma was a stout woman, standing all of 4-foot-6. This particular SS soldier was well over 6-feet tall.

“And he said a third time, ‘That picture is going to come down,’’ Van Herwynen said. “And she went like this with her hands on her hips, and said, ‘Now, you listen to me, young man. You hang your Adolph Hitler on the wall and we hang the queen on the wall.’ So the Germans slept in the bed with the Queen on the wall, for three months. And there was no picture of Hitler, just the queen.’’’

May 5, 1945 was liberation day. The country was largely in ruin, and over 205,000 Dutch men and women had lost their lives, over half (107,000) of which were Holocaust victims.

People were trying to put back together their lives as best they could, and Van Herwynen had met Tom and they were engaged to be married. But Tom was sent off to the war in Indonesia in May of 1947. In August, he was killed in battle.

Because Indonesia was Dutch territory, the bodies were not returned to Holland but buried there.

“That was tough,’’ Van Herwynen said. “I had had it. I had it with all the rigmarole in Holland. I thought, ‘Ah, the hell with it.’’’

She signed up to join the Navy and said she’d be willing to go to Indonesia. Her actual mission was to see where Tom was buried. She was 21 now, and her mind was made up.

But when the papers arrived at her home on where to report, grandma intercepted them. She gathered all of her kids together and then summoned Van Herwynen to her home.

As soon as she arrived, grandma had the papers in her hand.

“What is this?” she said to Van Herwynen.

“Grandma, I signed up for the Navy,’’ she told her.

“Oh, no. Oh, no,’’ said grandma. “Why do you want to do that?”

“Because I’m sick and tired of Holland. I’m just sick and tired of it, living here,’’ she told her.

“No, absolutely not,’’ grandma insisted.

“I looked grandma straight in the face,’’ said Van Herwynen, “and said, ‘You’re acting as if I’m going into a whorehouse.’ Oh, brother. That was the wrong thing to say.’’

Van Herwynen said it didn’t matter. She was 21 and could do what she wanted. Grandma said she didn’t care and was going to intervene nonetheless.

“And I knew she would,’’ said Van Herwynen. “I said, ‘OK, if I can’t join the Navy, I want to move away from this town. Because everybody knows me, and knows Tom, and knows what happened to Tom. I just couldn’t take that anymore.’’

Van Herwynen finally relented and agreed to move in with one of her uncles in the city of Oss.

It was here where a life that endured so much sadness began to turn.

She worked as a manager at a local business, and was befriended by another manager and his family. They were also friends with a man named Peter Van Herwynen.

“So one day my friend’s wife said to me, ‘Anne, why don’t you go out with Peter?’’ she said. “I said, ‘Huh?’ She said, ‘Well, he’s a good-looking guy. He’s from a good family and he has a good job.’ I said, ‘You know what? I wouldn’t go out with him if he was gold-plated.’

“Did I have to eat my words.”

Peter and Anne married and planned to move to Australia, but the Australian government bungled the application process. Peter suggested Canada. Anne balked.

So they moved to a southern province in Holland. Life there was good, but one day Anne received a letter from Peter’s brother, who had moved to the United States a few months earlier.

They had joked about following Peter’s brother to the States one day but now, in her hands, was this letter.

“You’d better get ready,’’ the letter said, “because you’ll like it here.’’

And in two years, there were on a ship crossing the Atlantic.

“It was hard on the family,’’ she said. “But I had to do it.”

They arrived in Hoboken, N.J. with two small children, three train tickets to Chicago and $100 in their pocket.

And that worried her more than anything that happened between 1939 and 1945.

“If I think about it now,’’ she said, “it scares me stiff.”

But Peter’s brother was able to get him a job at Behm Motors in Appleton, Wisconsin before they stepped foot in town. They arrived on a Friday night, and Peter started work Monday morning.

Anne would eventually go on to work at a local hospital, Appleton Medical Center, for 27 years, starting as a nurse’s aide, then as an EKG and EEG technician and was a part of starting the hospital’s sleep lab before she retired.

Dorothy Nelson, Van Herwynen’s daughter, has heard all the stories and to this day sits in amazement when it comes to her parents.

“Between my grandmother, and even mom herself, they showed a resistance to some things that I don’t know if I would have had the strength to do,’’ she said. “It’s pretty hard when you’re a young person and you’ve got the war going on around you, to make some of the decisions that she did, keeping her own personal values upfront, too.

“She always tells the story where (Adolph Hitler) paraded by and she refused to raise her arm, and that still sits with me now. Even when there’s TV shows on, I’ll think about that. It’s amazing to have been part of that, and again show her defiance in her own way, and that’s a way of cheating death because if you do that to the wrong person, you were out.

“And I’m still unsettled when you see the SS uniforms, and the movies with them in it, and how cruel they were and that it didn’t take much to get killed. So to have the strength to be able to stand up to them is pretty amazing.”

When people speak of The Greatest Generation, they mostly consider it from an American point of view.

But Dorothy knows people like her mom, grandmother and the people from countries like Holland, are very much a part of it.

“We’ve always been proud of my mom and dad, and the guts it took to come over here and start a new life, and the strength and character that they had in dealing with their circumstances,’’ she said. “I’m sure there were thousands of other people that went through the same thing. I’m sure they had memories, both good and bad, of the war times but they made a life for themselves and I think a lot of people that age, just moved on – took each day at a time and built a new life.

“I admire my parents and the other people like them who had the ability to move forward.”

It’s been a long, eye-opening and emotional afternoon with Anne Van Herwynen but, before she says goodbye to her guest, she thinks of one more tale to tell. She lets him know that she, too, worked for the Underground.

She was part of a secret message service that carried the locations of allied pilots who were shot down, so they could be rescued, put in the Underground — moving from farmhouse to farmhouse at night — and brought back to England.

“There was a whole setup,’’ she said. “I would bring the message to the next one who had to pick them up.’’

And given everything she has told you, you didn’t have to ask. She knew her life was in jeopardy each time she began to pedal with one of these notes.

“Kind of,’’ she said. “I don’t know. I didn’t think about it. I was just a girl on a bicycle.”

And then her eyes light up.

“You what I did when I was young, and I loved it?’’ she said. “The German soldiers would stop you and ask for directions, and I’d always give them the wrong ones. Why in the hell should I give them the good ones?”

You laugh and shake your head, and Anne looks at you with a knowing smile.

“I survived,’’ she said.

Story idea? You can reach Mike Woods at 920-246-6321 or at: michael.t.woods1@charter.com

Read part one, here.

Read part two, here.