ASHLAND COUNTY, Wis. — Mark Edlund and David Burge know their way around a diatom.

The two scientists, who both work at the Science Museum of Minnesota, spend a lot of time peering at these organisms — single-celled algae that have evolved to protect themselves in glassy silica shells.

“You know you've been looking at diatoms long enough when you lay down to go to sleep at night, and all you can see is a microscope slide and the diatoms on it,” Burge said.

But when Edlund looked at a sample from Wisconsin’s Apostle Islands, he saw a shape that didn’t seem to have a match among all those mental images.

“We thought, ‘Huh, I wonder if this is something new,’” Edlund said.

As it turns out, they were right. The diatoms they’d picked up belonged to a species that had never been seen before.

The researchers officially described the new species, which they named Semiorbis eliasiae, in a recent study, solidifying it as the latest addition to the tiny world of diatoms.

“It's not something you get to do every day in science, to actually discover something brand new,” Edlund said. “To see something that no one else has ever found before.”

Shaping up

The researchers didn’t actually set out in “discovery mode,” Edlund explained — but “with diatoms, there is always this chance that you will run into something new.”

For more than a decade, Edlund has partnered with the National Park Service on a project to keep tabs on different Great Lakes parks, including the Apostle Islands National Lakeshore. His team happened upon the new creatures as part of this monitoring effort.

Some of that work involves pulling up sediment cores — tubes of mud suctioned up from the bottoms of lakes whose layers lay out an ecological timeline. Diatoms, in particular, are useful for monitoring, Edlund said: Their silica shells tend to stay well preserved over the years, and their populations respond quickly to shifts in nutrients, water pH or other factors.

“They're a tool that we use to understand how environments have changed and are changing,” Edlund said.

Back in 2007, the monitoring team took a sediment core sample from Outer Lagoon — a shallow body of water way out at the tip of the park, formed when currents piled up enough sand and gravel to separate it from the rest of Lake Superior.

And in the lab, Edlund discovered that the core included something special: Diatoms from the unusual Semiorbis group.

“It's hard for me to convey how rare this thing is,” Edlund said. “Honestly, I have been studying diatoms for over 30 years, and this is the second time I've ever collected this genus in my whole life.”

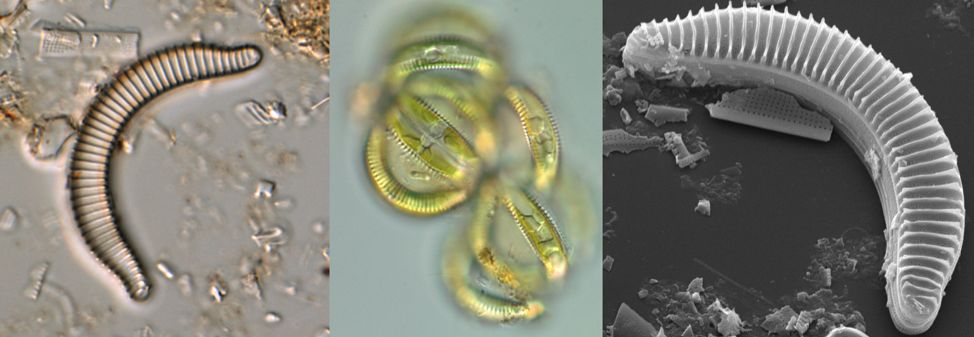

Semiorbis species have a unique shape, Burge said. They look like little half-moons instead of the squares or circles that are more common for diatoms.

But the Apostle Islands samples didn’t look like other Semiorbis types that were already in the books, Edlund said. Eventually, he and Burge decided to take a closer look at whether this diatom could really be something new.

After reaching out to other researchers from around the world, they got their hands on a few different Semiorbis samples from New Jersey, Florida, Norway and Canada. When they set the Apostle Islands against this global array, “this is where it just jumped out at us that it was different,” Edlund said.

If you unbent one of the Wisconsin diatoms from its semicircular curve, you’d have a pretty uniform shape that looks a lot like a pencil, Burge said. Other Semiorbis species would be a little wavier, showing different wide and skinny sections.

With some more technical analysis of the shapes, the scientists confirmed that the Wisconsin diatoms were distinct enough to be named as their own species. Edlund picked out the name Semiorbis eliasiae after his colleague, Joan Elias — a retired NPS water quality specialist who helped set up the monitoring collaboration in the first place.

For Burge and Edlund, this isn’t their first new-species rodeo. Burge said he’s now been involved with five diatom species discoveries; Edlund said his count is over 60.

Still, the researchers said that the chance to uncover something new is a big part of the thrill of science.

“I love space and exploration, the discovering or venturing into the unknown,” Burge said. “And when I realized that I wouldn't be going into space, the next best place to examine the unknown was through a microscope.”

Little algae, big impact

Even if you’ve never seen a diatom — and you probably haven’t, unless you’ve squinted through a microscope to check one out — you’ve definitely felt the impacts of the teeny-tiny organisms, Burge and Edlund said.

Let’s pause for a second. Take five deep breaths. In, out, in, out …

You should thank diatoms for one of those five breaths, Burge said: “They play a significant role in providing oxygen for the planet and clean air that we breathe.”

Like other plants, diatoms go through photosynthesis — taking in sunlight and turning it into energy. And like other plants, through that process, they also suck up carbon dioxide and turn it into oxygen.

Algae, in general, produce about half of the oxygen we breathe, Burge said, and diatoms in particular pump out about 20% of it.

Plus, Edlund pointed out, they make up the base of the food web for many aquatic ecosystems. The energy they soak up from the sun gets eaten and passed along by fish, which in turn provide food for ospreys and eagles (or even humans).

Diatoms are pretty much all around, Burge said. And they’re a diverse bunch, with tons of different species suited to different homes.

“In rivers, lakes, wet walls, the moss on the side of trees, the oceans, under ice sheets, diatoms have made life in all of these very unique aquatic environments,” Burge said. “You just need a little bit of moisture.”

While there are already 30,000 diatom species recognized by scientists — now including Semiorbis eliasiae — estimates show that there could be as many as 70,000 more waiting to be uncovered, Burge said.

These days, there’s better technology and more “trained eyes” watching out for new diatoms, Burge said. So maybe Semiorbis eliasiae should enjoy its time in the spotlight since some other new and shiny species is sure to come along.

Getting a better handle on these species now will be key to understanding how things are changing in the future, Edlund said. Having a baseline is useful for projects like the NPS partnership, which uses diatom communities to measure shifts in whole ecosystems.

And, of course, a new species is something that just “gets those scientific juices flowing,” he said.

“The take-home message for me is that scientific discovery still happens at this most basic level,” Edlund said. “We can still go out in this world and find something absolutely brand new that no one else has ever seen, no one else has ever collected, and bring that out for the world to see.”