MILWAUKEE — After graduating from Marquette University in the middle of the COVID-19 pandemic last spring, David Fraley was able to land a full-time job as a software engineer. So why did he decide to take on extra, unpaid work on a vaccine management project?

“I just don’t like to sleep,” Fraley jokes.

In reality, Fraley says, “COVID has affected me personally, in various ways — none of them positive. I have some skills that can help stop COVID. And if I can help, if I can do my part, then I will.”

Fraley is the project manager for MassVaxx, which is creating an open-source software system to help COVID-19 vaccinations run more smoothly. The goal is to build out two websites, one for patients to register and another for health care workers to track the shots, that can easily be booted up by health departments or other vaccinators.

With this effort, the team — mostly made up of Marquette students and faculty, plus some Rochester Institute of Technology students and professional developers — hopes they can help get shots in arms more efficiently and put an end to the pandemic.

Even before COVID-19 swept the world, the need for a digital vaccine management system was clear, says Marquette professor Dana Cook and a coder for MassVaxx. Early in 2020, Cook had already been in talks with the Southeast Wisconsin Incident Management Team about recruiting students for a coding project.

Emergency management experts predicted that in the case of a pandemic, getting lots of vaccines out would be “kind of a disaster,” Cook says, since most health departments relied on plain old pen and paper to keep track of information.

“We started hearing about COVID, and didn't really know the extent of what would happen,” Cook says. “But we started talking about this as a long-standing need that has never been met.”

Of course, as the novel coronavirus continued to spread, that long-time need became even more relevant.

Cook and another Marquette instructor, Teri Sippel Schmidt, started rounding up students to kick off the project at a hackathon over the summer. After that session, Cook says, they’d produced only a “quick and dirty” version of the software — but they ended up with a growing team that wanted to keep the effort going.

“We regrouped, and we were thinking, ‘Hey, we can actually do something real with this,’” Fraley says.

The all-volunteer group, now more than 20 strong, has been working for months since those early days to develop the software into a usable product. And MassVaxx has come a long way since the original rough draft: Fraley says they’re almost done with development and looking to do some real-world testing in the next couple weeks.

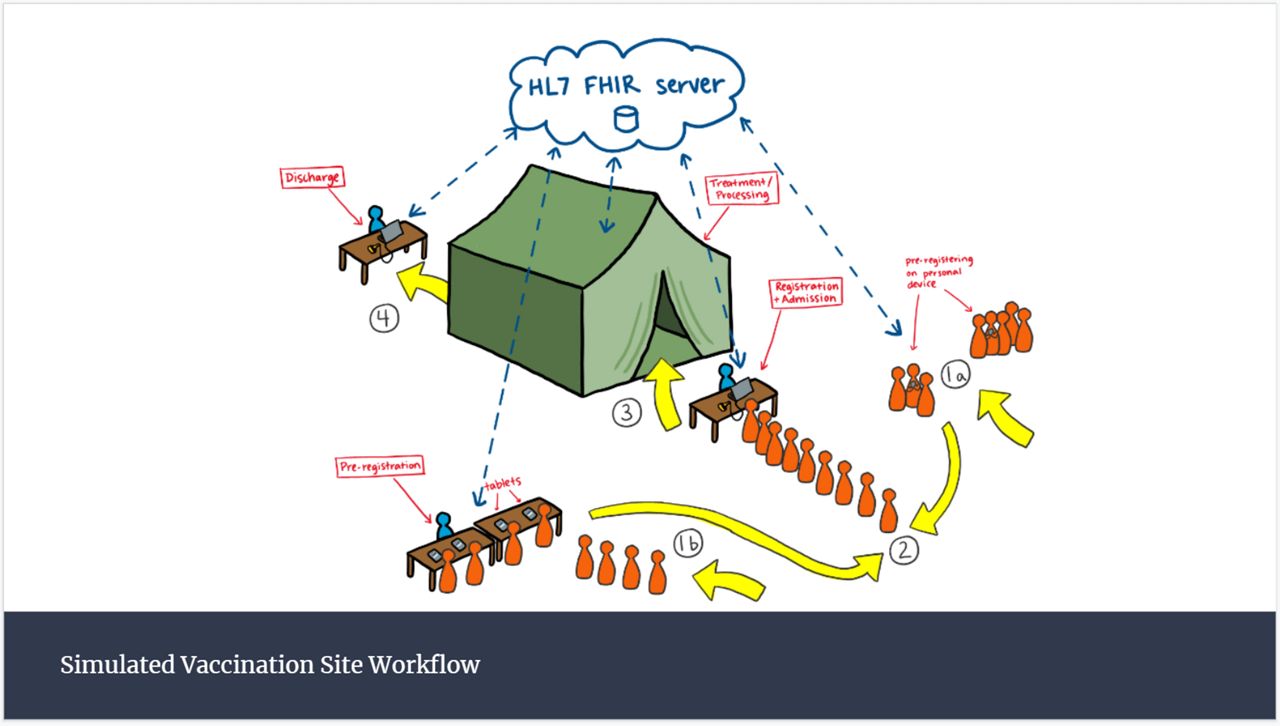

Their current product has two sides, explains Shahd Sawalhi, a Marquette junior and front-end software developer for MassVaxx. On one side, there’s the patient registration system — what “actual citizens” would use to input their information and get a QR code for check-in, she says.

And on the other, there’s the point of dispensing app, which would be used by nurses or other workers who are giving out the shots. The POD app would let vaccinators track every step in the vaccine workflow — from documenting the dose they use to monitoring any adverse reactions — and send that data to the Wisconsin Immunization Registry, Sawalhi says.

All of this would hopefully help local health departments move patients through the vaccine process quickly, while still securing all the important data they need, the team members say.

Sawalhi says seeing the bumps in the vaccine rollout so far — with people left waiting in long lines to get their shots, and information only taken down on paper — underlined the importance of making the vaccination process run efficiently.

“There was that inner drive or motivation, putting all the knowledge and the effort you can to stop this thing, which is COVID,” she says. “I feel like that was a motivation for most of the team.”

Many of the MassVaxx team members also felt strongly about keeping their code open-source, Cook says, rather than charging a fee for counties to run the software. Other data management tools can be pricey, she says, and under-resourced health departments may not have the funds to keep them on hand in case of emergency.

If anyone in Wisconsin or beyond wants to use the MassVaxx software, Fraley says, the team can easily help them install it, leaving only the limited costs of getting an actual website up and running.

“We don’t care who takes up our software,” Fraley says. “We just want to stop COVID.”

Though they’re in the process of incorporating a nonprofit to account for some expenses, Fraley says they’ve been all self-funded so far, relying on team members to volunteer as much time as they can manage. He says it’s sometimes been a challenge to find the right balance between day-to-day commitments and MassVaxx, since “there’s always more work that needs to be done on the project,” he says.

And for some of the team members, the project created a pretty steep learning curve, Cook says. Some, like Sawalhi, didn’t have much coding experience at all, or were working with new coding languages and tools. Cook herself says she hadn’t written a line of code in years before starting on the project, but has enjoyed being “in the trenches” working on development with the rest of the team.

“This was a really good chance to get back in ... and teach in a different capacity than in the classroom,” Cook says. “I’m learning, and they’re learning; we’re working through problems together.”

Fraley says MassVaxx has been in talks with a handful of groups, including some Wisconsin counties, who may be interested in using the software. He’s looking forward to getting the development side wrapped up so they can focus on installing the software for whoever needs it — reaching a point where “we’re actively stopping COVID.”

The software they’re developing could also have uses beyond our current crisis, Cook adds. Their tools could help out in future pandemics that require mass vaccination clinics, as well as hurricanes, floods, or other natural disasters where lots of people are seeking medical attention.

In the end, the team members say, they’re just hoping their work can be put to use.

“If anyone uses this anywhere, to any capacity, I think we'll all feel like we accomplished something,” Cook says. “We’d be OK with that.”