MILWAUKEE — When a person catches COVID-19, they can shed the virus that causes it in a few different ways. Mostly, this happens through the respiratory system: Sneezing, coughing, breathing, talking.

But scientists have learned that the SARS-CoV-2 virus also exits out of another end of the body — the back end, to put it delicately.

Sandra McLellan, a professor at UW-Milwaukee’s School of Freshwater Sciences, learned from early reports out of China that the virus’s genetic signature could be traced in feces. For McLellan, who has spent years studying wastewater, the research sparked a “light bulb.”

“That was a little unexpected because, when you think about viruses, they’re very specific to different body sites,” McLellan says. “So the fact that it actually passed through the body that way gave us the opportunity to say, ‘Hey, this is a way we can track it.’”

Over the course of the pandemic, researchers in McLellan’s lab, along with collaborators at the State Laboratory of Hygiene in Madison, have been working on ways to follow the coronavirus through Wisconsin’s pipes and sewers. In December, they launched a wastewater surveillance dashboard with the Department of Health Services, which shares real-time data on how much viral RNA is showing up in samples from across the state.

As of Wednesday, all of the regions on the DHS dashboard showed viral concentrations in wastewater were decreasing or showing no significant change — mostly in line with the state’s case rates, although some areas are seeing their infections tick up in recent weeks.

Unlike other COVID-19 surveillance, which relies on individual people’s nose swabs or spit vials, the wastewater method takes more of a bird’s-eye view. “It gives us a picture of what’s happening in the whole community,” McLellan says.

The researchers get bottles of sewage from wastewater treatment plants across the state, which pull in wastewater from their regions over a course of 24 hours.

The result is a mixture of everyone’s waste — including their coronavirus traces, says Dagmara Antkiewicz, an environmental toxicologist at the State Laboratory of Hygiene who’s working on the project.

“Everybody uses the bathroom,” Antkiewicz says. “So you really have that well-mixed sample that represents the population.”

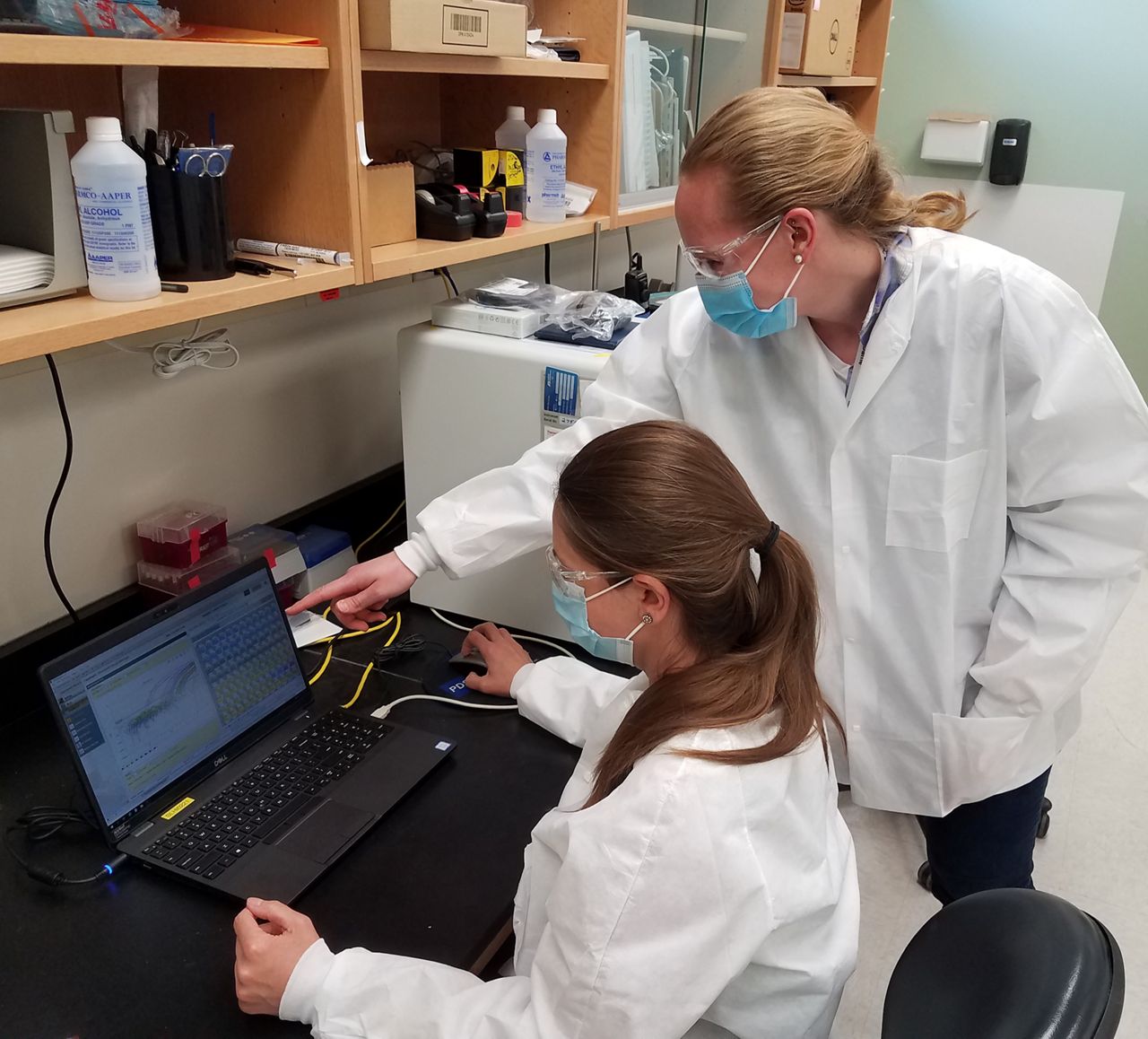

These days, the two labs are testing samples from around 70 plants in the state, covering more than half of all Wisconsinites. The UW-Milwaukee lab focuses on the populous southeast region, McLellan says, while the State Laboratory team takes in samples from a wider range of plants across the rest of the state.

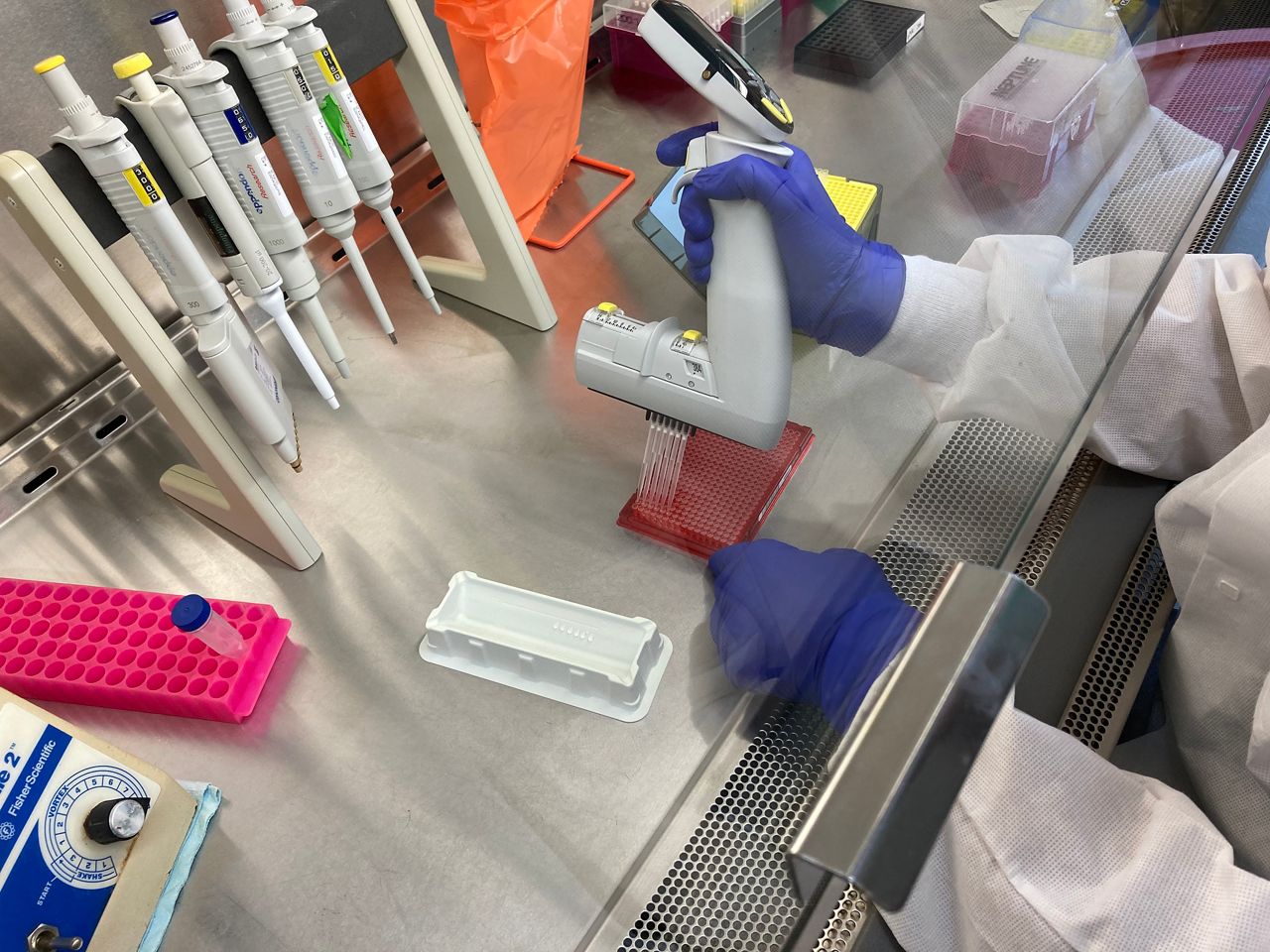

When the samples arrive, the researchers prep them for testing: First, they spike the sewage with different viruses that affect cows. These will serve as a control in the testing, to confirm that everything in the sample is showing up properly in the results, Antkiewicz explains.

From there, the mixture is run through a filter to separate out the useful stuff from the part that’s just, well, waste. The filter is shaken up with solution in a “bead basher,” which contains tiny beads that break the whole filter up into a liquid. Then, an RNA extractor pulls out the genetic material from the now-liquefied sample — leaving the lab workers with the genetic material they need.

The genetic testing uses a similar process to the diagnostic COVID-19 tests, McLellan says: It’s a PCR process that seeks out any bits of coronavirus RNA that are floating around in the sample. Instead of just giving a positive or negative signal, though, the test quantifies how much virus is present.

In this way, wastewater surveillance can give important insight into how much virus is flowing through a whole community — and whether other forms of testing are missing a trend.

Tracking COVID-19 in sewage doesn’t rely on people going to get tested themselves, Antkiewicz points out. So, in areas where testing is harder to come by, or at times when people are fatigued and not getting swabbed, wastewater testing may catch outbreaks that would otherwise fly under the radar.

“In areas where there's less testing, you might have a very different picture looking at the sewage from the one that you're getting from clinical tests,” Antkiewicz says.

Plus, as the DHS website points out, people may be shedding the virus (into the air and into the toilet) before they feel symptoms, so wastewater can give a bit of an advance warning for what’s to come. Some institutions — including dorms, nursing homes, and schools — have put targeted wastewater tracking in place as an early detection system.

Of course, McLellan points out that the wastewater testing isn’t a self-standing method: We still need pinpointed clinical testing to tell us who exactly is sick. Wastewater tracking offers just one more tool in the toolbox of the state’s pandemic response, the researchers say.

Moving forward, Antkiewicz says the team is hoping to expand their reach to even more plants across the state. They’re also considering more frequent sampling to more closely trace the ups and downs of coronavirus concentration.

And as immunity from COVID-19 vaccines starts to kick in, McLellan adds that wastewater monitoring will be useful to track infections as they hopefully dip down — or watch for any unexpected resurgences.

“It will be a confirmation that, yes, indeed, we’re actually getting ahead of this,” McLellan says. “And we’ll be glad at some point when we can’t detect it.”

Both scientists stress the importance of collaboration — with each other, with other partners across the state, and with fellow researchers all over the world — in making this tracking system work.

McLellan says she’s been holding regular calls with other experts to talk shop, and leads a nationwide team that’s creating a blueprint for starting up wastewater surveillance systems. The two Wisconsin labs are also part of an international collaboration with its own global “COVID19Poops Dashboard.”

The researchers are hopeful that wastewater surveillance could become a standard tool for other public health issues too — tracking lead levels, for example, or opioid use.

For now, though, their focus is on the current crisis: A pandemic that’s kicked off a “rollercoaster” of scientific problem-solving, as Antkiewicz calls it.

“Anybody who works in research, you want to be able to make a difference, and improve the situation, and advance science,” McLellan says. “So having such a real-world problem unfolding at your feet and watching it on the news every night really was a motivator for, ‘OK, let’s figure this out.’”