MILWAUKEE (SPECTRUM NEWS) — Last week, Bieneke Bron spent a day exploring the lush greenery in a state park — like many of her fellow Wisconsinites will do this summer. But she wasn’t there to simply enjoy the great outdoors.

Bron, a postdoctoral researcher at the University of Wisconsin-Madison, was on the hunt for a tiny threat: the black-legged tick. Also known as a deer tick, this arachnid is notorious for its ability to spread illnesses like Lyme disease to humans.

Bron and other researchers have been surveying parks across the state to figure out where the ticks are living and help people protect themselves from the “nasty disease agents” they carry. The “tick team” also created a mobile app that lets people submit their own data to help with the research and offers information about safety.

“There is no one solution to stop Lyme disease and tick-borne diseases. So that's really frustrating,” Bron says. “What I hope that our research can accomplish is that we will have developed better strategies to prevent tick-borne diseases.”

The Wisconsin tick invasion

Lyme disease spreads when infected ticks bite humans and transfer the disease-causing bacteria — most commonly, a bacterial species called Borrelia burgdorferi. Often, these bites are from tiny nymphs: immature ticks that haven’t yet grown to full size, which are mostly active in the spring and summer, according to the Centers for Disease Control.

In order to transmit the bacteria, ticks have to be embedded on the body for a long time, around 36 to 48 hours, the CDC reports. But once they’ve latched on, they can be hard to spot, since they often attach to hidden areas like armpits, belly buttons, and scalps. The nymphal ticks are especially tricky because they only measure about 2 millimeters wide.

“If you find a tick, and you're like, ‘I had no idea this tick was here. Man, it's only the size of a poppyseed’ — that's the nymph,” Bron says.

Deer tick populations have been spreading throughout Wisconsin since the 1970s, Bron says, starting out mostly in the northwest parts of the state.

Today, the ticks have made their way to pretty much every corner of Wisconsin, which is one of the top states for Lyme disease cases in the U.S. The Wisconsin Department of Health Services estimates that 3,105 people were infected in 2018 — a rate that has more than doubled over the past decade.

Ticks have probably been in Wisconsin for thousands of years, from when the glaciers that once covered parts of the state started receding, says Susan Paskewitz, an entomology professor at UW-Madison. Around 1900, humans destroyed a lot of the ticks’ habitat by cutting down the trees where they like to live and hunting the white-tailed deer they like to feed on, so the populations plummeted, she says. But as some of the landscape has reverted back to forest, the ticks have bounced back too.

“It's taken a while, but now they're everywhere,” Paskewitz says. “And they continue to move not just in Wisconsin, but in the upper Midwest.”

Paskewitz says the tick team has been working to identify all the places where ticks live in Wisconsin.

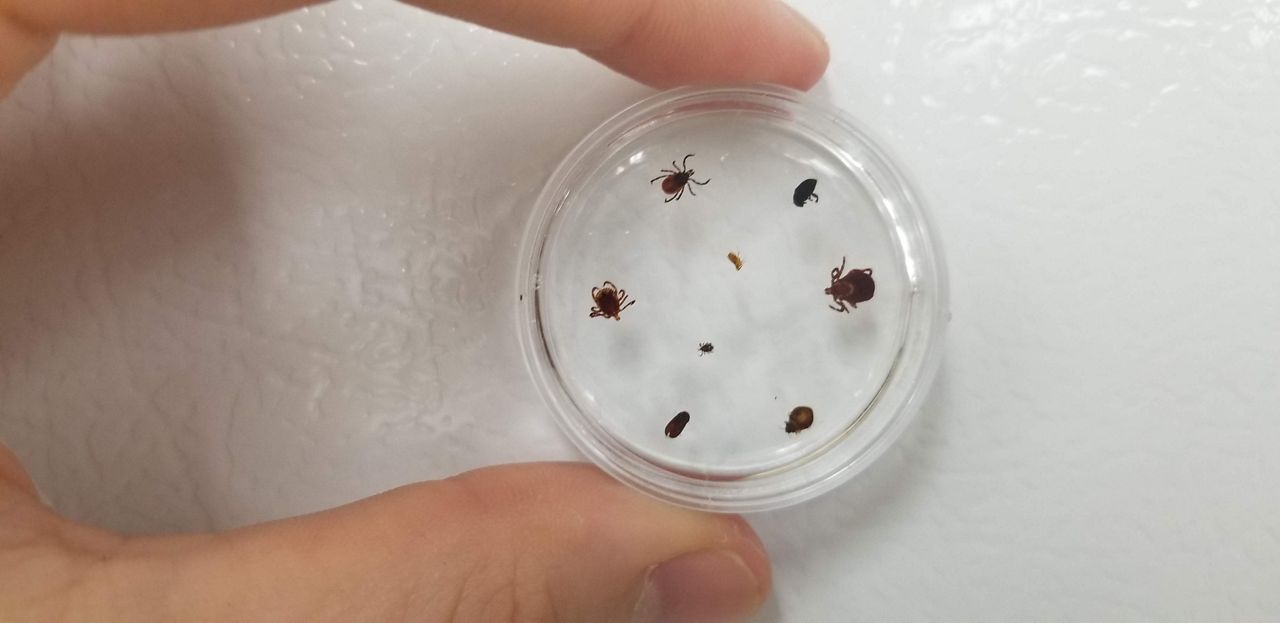

In their fieldwork last week — which involved dragging a big sheet of white denim across the forest floor and checking the critters that get picked up — the researchers found enough ticks to officially establish a population in Dodge County. Now, Winnebago County is the only one left in Wisconsin without an established tick population, Paskewitz says, although the research team plans to keep checking the area.

Because the deer ticks have dispersed so much over the past couple decades, Paskewitz says Wisconsinites, including health care providers, don’t always realize how widespread they are. Earlier this month, the team did a “blitz” of 15 parks in the Madison area and found ticks at seven of them. They’ve even found ticks in people’s yards, Paskewitz says, meaning tick prevention steps could be important even if you’re just out mowing your lawn.

“There still seems to be some confusion or lack of information, really, amongst a lot of people about where you can actually pick up these ticks,” she says. “A lot of people know that if you go to northern Wisconsin, you'll get them — maybe if you're out at your cabin in our beautiful Northwoods. But they're not as sure about if you're living in Milwaukee, for example.”

Tick science in your pocket

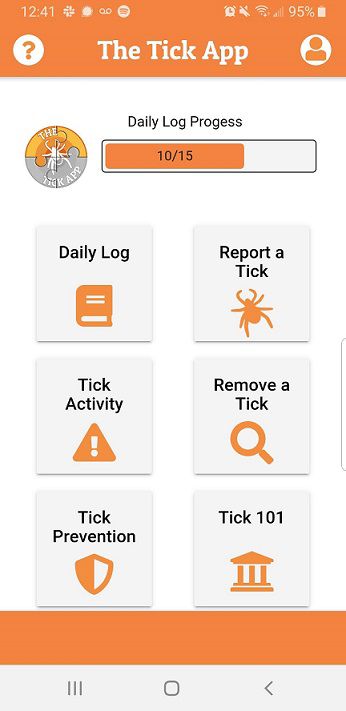

Everyday people can also contribute to the tracking effort through the Tick App — a free smartphone app launched in 2018 to help crowdsource information and provide educational resources.

The app, which UW-Madison developed along with researchers from Columbia University and Michigan State University, gives the team insight into people’s encounters with ticks, Bron says. Users are encouraged to fill out daily logs about their outdoor activities, any prevention methods they used, and whether they found ticks on any household members — humans or pets.

This year, 3,000 people in the U.S. have used the Tick App, including 620 from Wisconsin, Bron says. The researchers have gotten more than 5,000 daily logs so far.

“That project has been really exciting because it's allowed us to ask a lot of questions of citizen scientists who enroll in the Tick App,” Paskewitz says. “It's a research tool.”

By learning more about people’s habits, researchers get a better idea about what kinds of public health information people need, Paskewitz explains. For example, by comparing responses from Wisconsin and other tick hotspots like New York and New Jersey, researchers have seen that Wisconsinites spend more time doing outdoor activities like hiking and camping — and are more likely to mow their own lawns.

Plus, the Tick App provides information on how to identify ticks and prevent bites, including warnings about potential tick activity in the area. If they think they’ve found a tick, users can send photos to the tick team for confirmation.

“I hope it really serves sort of a public health piece,” Bron says. “That it helps people better understand what ticks are and how to protect themselves, and which ones are the dangerous ones and which ones are really a nuisance.”

How to stay safe from bites this summer

So far this summer, Paskewitz says the tick team has found relatively low numbers of ticks in the parks they’ve surveyed. In their early June “blitz,” the researchers picked up 11 adult deer ticks and eight nymphs, Bron adds. But this could have to do with outside factors affecting the collection, like weather conditions, and researchers expect the numbers of nymphal ticks to increase over the course of the summer.

So how can Wisconsinites keep themselves safe from Lyme disease — or other tick-borne illnesses — as they’re enjoying the great outdoors?

“Just being aware that you need to protect yourself if you're going to be outside in an area where you could be exposed to ticks,” Paskewitz says. She recommends using repellent and wearing clothes that have been treated with permethrin, a chemical that repels ticks and can also kill them before they embed on your body.

It’s also a good habit to perform regular tick checks on yourself and other family members or household pets, Paskewitz adds. Make sure to keep an eye out for the tiny nymph “teenagers” that are harder to spot than the full-grown ticks or even bigger wood ticks, a separate species that doesn’t transmit Lyme.

When going out for a hike, Bron advises staying on trails instead of wandering into wooded areas where ticks tend to thrive and tucking your pants into your socks to limit skin exposure. And once you get back, make sure to shower and toss your clothes in the dryer to get rid of any ticks that might have hitched a ride home with you.

If you do feel like you’re coming down with something, Paskewitz says, make sure you tell your health provider about any possible tick exposure so they can consider Lyme disease or any of the other tick-borne diseases, like anaplasmosis or babesiosis.

Lyme disease can be hard to identify because its symptoms are pretty generic, Bron says. If you have flu-like symptoms in the summertime, including fever and aches, Lyme is definitely a possibility. Of course, the coronavirus crisis adds another layer of complication — but unlike COVID-19, Lyme disease won’t make you cough, she says.

Even though most Wisconsin residents know about tick-transmitted diseases, they don’t always take all the proper measures to protect themselves, Bron says. Through their work, she says the tick team hopes to close that gap.

“Almost everybody we run into will say, Oh, I had Lyme disease, or someone else had Lyme disease, or my dog had Lyme disease,” she says. “But it’s one thing to be aware, and another thing to take action.”