MADISON, Wis. – Amid the pandemic, there has been lots of talk about tax credits leaving many people wondering about what they really mean and how they can help Americans.

Former House Speaker Paul Ryan hopes two of those reforms can reduce poverty and grow the economy. He moderated a virtual conversation about the Earned Income and Child Tax credits on Friday.

Ryan, who once led the House Ways and Means Committee, still has a lot of ideas about how to improve tax credits.

The American Idea Foundation hosted a bipartisan discussion to talk about ways to improve policies like the Earned Income Tax Credit (EITC), which helps low- to moderate-income workers and families get a tax break.

“The highest marginal tax rate isn't, you know the best quarterback in the world, Aaron Rodgers," Ryan said. "It is paid by, you know the single mom who's working her way out of poverty who loses these benefits and all of a sudden loses like 80 cents on the dollar."

Experts said the EITC is a big way to incentivize employment, but its efficacy has been limited with so many losing jobs during the pandemic.

“Better infant health, better school performance, higher college enrollment, higher earnings in young adulthood,” Diane Whitmore Schanzenbach of Northwestern University said of the credit's benefits. “This is an investment that pays off over, you know a lifetime.”

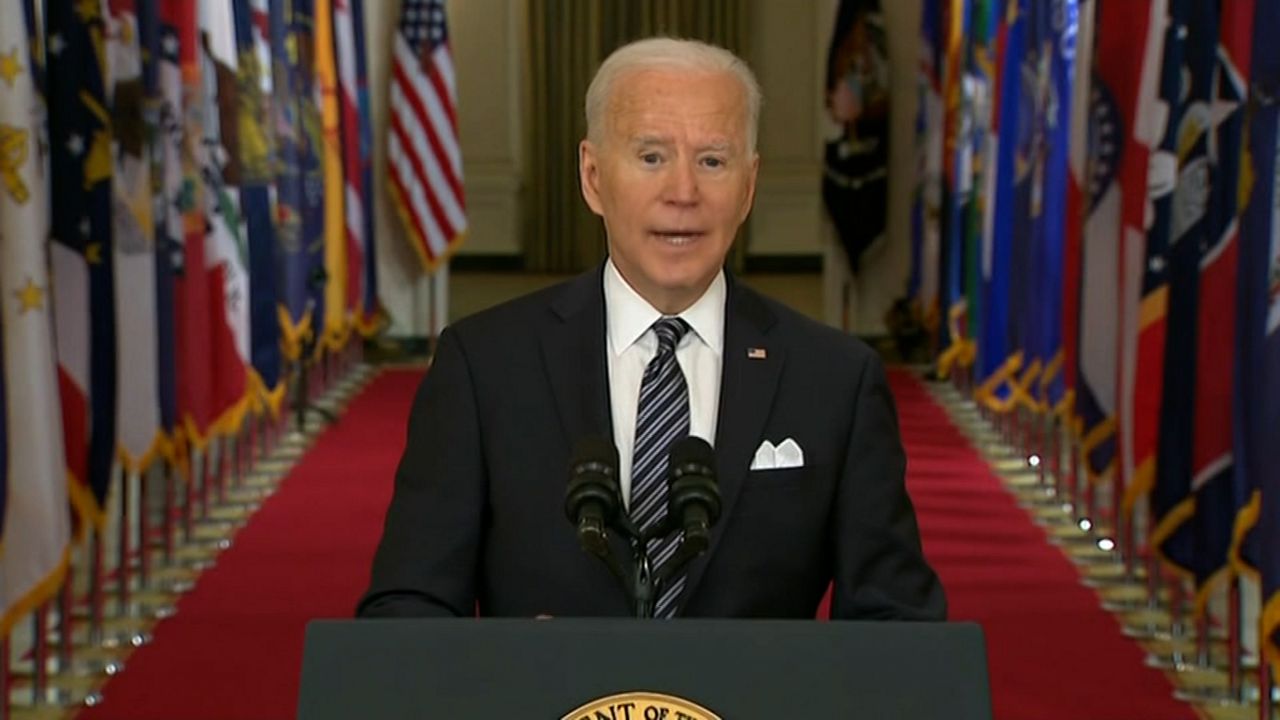

The $1.9 trillion American Rescue Plan signed by President Joe Biden last month temporarily increases the Child Tax Credit (CTC) from a max of $2,000 to as much as $3,600 per child.

Families will get a $3,000 annual benefit for each child ages 6-17, and $3,600 for each child under the age of 6 for the 2021 tax year.

Expanding the amount, and who qualifies, could incentivize the life choices many people make.

“I do think policies like the Child Tax Credit, and reforms to it, can encourage more family formation, more children on the margin,” Scott Winship of the American Enterprise Institute said.

Other experts want to take it a step further and allow the credit to be borrowed up front.

“So our idea was that these dollars, upfront in the child's life when it's most important to a child's development, give parents a lot more choice in how and who is going to be raising their kids,” Katharine Stevens, also of the American Enterprise Institute, said.

Instead of spreading the credit out as a child grows up, Stevens thinks getting the credit in one or multiple lump sums sooner could be more beneficial to help make it affordable for a parent to stay home or get higher-quality child care.

Assuming it is the maximum credit, and the parent has sufficient work earnings for the life of the child, there is a total of $34,000 available, according to Stevens.

“Our thought was it's kind of dribbled out over these years where, by the time the kid is 16, you're earning more money, the kid is not in childcare, you may not even notice it,” Stevens said. “So, what we proposed was allowing parents to borrow up to $30,000 of their lifetime child tax credit in the first five years of the child's life.”

Regardless of a possible solution, the whole point of bouncing ideas around Friday was about finding ways to improve anti-poverty tools for policymakers.