It’s called rock bottom. But there really isn’t such a place. Not in this world. Rock bottom is death. That is the only point where things can’t get worse.

Stephanie Good danced with rock bottom, time and again. But cheating death was never a deterrent. It was a green light to continue on her path of self-destruction.

Drugs were the reason her life was circling the drain. She overdosed twice, and each time NARCAN had to be used to bring her back. She was involved in a near-fatal car accident, after which she could hardly walk. She was put in jail multiple times. Someone sprayed bear mace in her face during a drug deal. She was assaulted and beat up in other drug deals. She watched friends overdose, then die.

“And I still continued to use,’’ she said.

She got pregnant. Then she made an appointment with Planned Parenthood.

“I was like, ‘I can’t do this. I can’t bring this child into the world. They’ll have nothing,’” said Good.

She went to the appointment. But her Catholic upbringing took hold.

“I couldn’t go through with it. I needed to keep the baby,’’ she said. “It was just a defining moment in my life, because I always would say, ‘I’m hurting nobody but myself with my addiction.’"

“And that’s not true. I was hurting my family and the community and so many people. But at that point, it was like, ‘Now my actions are affecting someone other than me. I literally have another human being inside of me.’ That was my wake up call.”

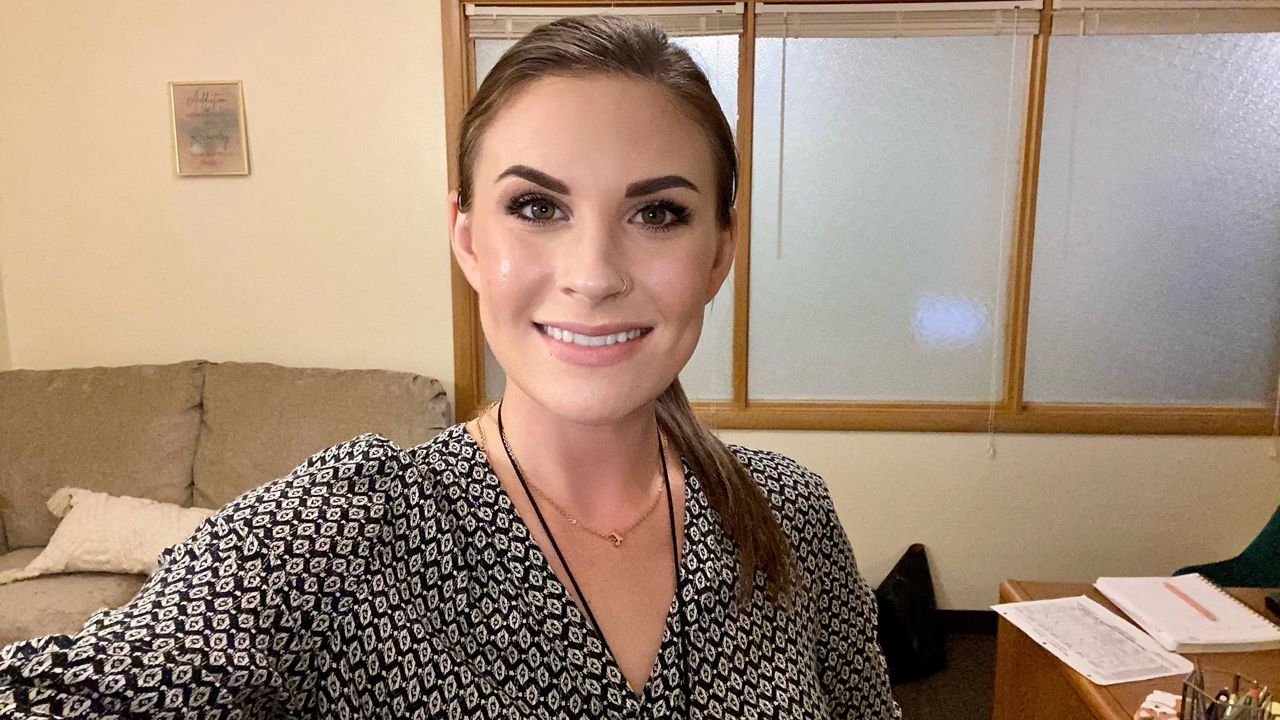

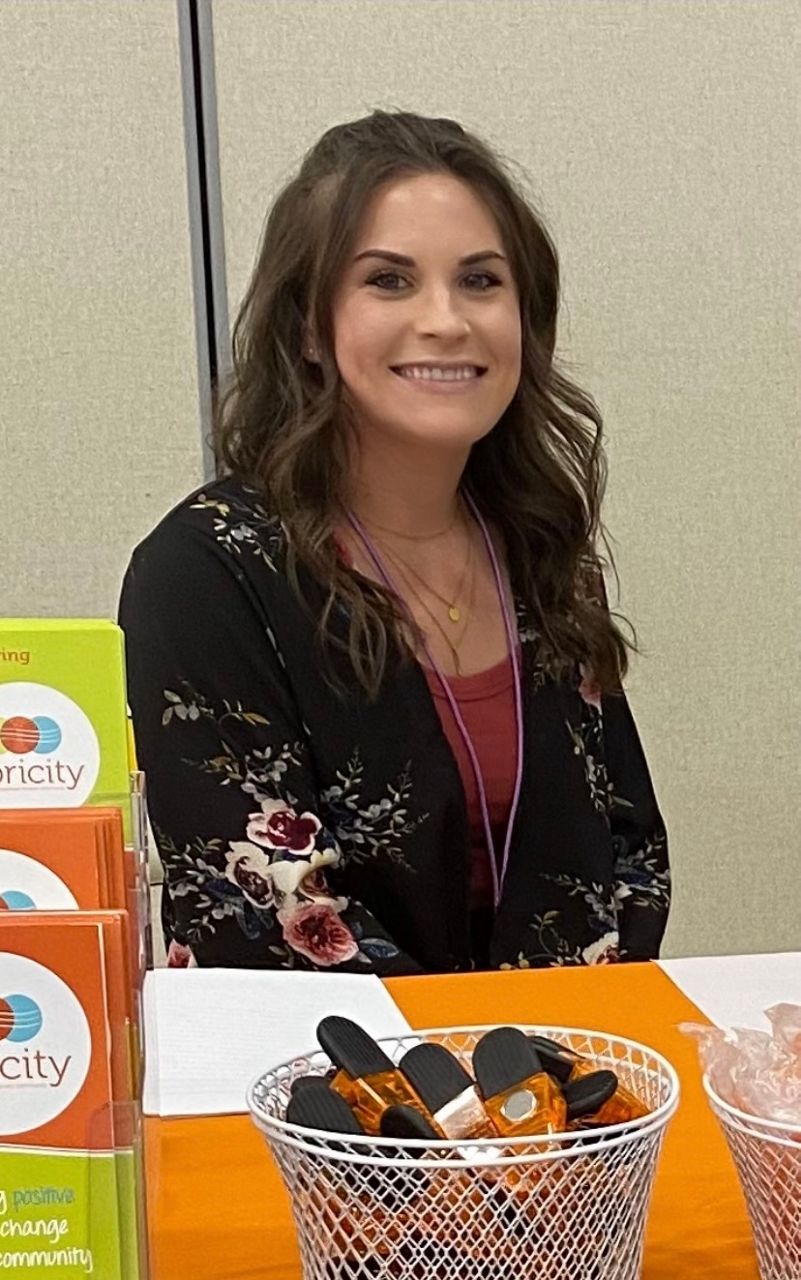

When Stephanie Good wakes up today, she’s a loving mother to her six-year-old son and a drug counselor at Mooring House, an addiction treatment center in Appleton.

“Freedom is the only word that comes to my mind,’’ she said. “When you’re in active addition, you’re a slave to a substance and you can’t function without that. Just to be able to function and not need something to feel good anymore, that’s the best feeling in the world to me.”

A feeling that took years to discover, and no drug could ever exceed.

****

No one could have ever guessed this could happen to Stephanie Good.

Grew up in the small town of Neshkoro in what she says was a picture-perfect childhood. Drugs were never part of the family tree.

But as an only child, she spent most of her time around adults. When school rolled around, she felt socially awkward. Classmates picked up on this, and the bullying began. She felt like she didn’t fit in anywhere.

“And it was the most important thing to me at that time,” she said, “to be well-liked and to fit in.”

Depression was also an issue. She was especially close to her grandfather, who died when she was 13. It devastated her. They put her on medication for her depression.

When she got to high school, she noted the cool kids liked to party. That involved smoking pot and drinking beer.

“I thought I could connect with them in that way,” she said. “I didn’t really think twice about it. I just was happy that I was invited to go to lunch with them and thought it would be like a bonding experience. “And I think that was reinforced because when I smoked (marijuana), I felt better. And I wasn’t so socially awkward.”

Things escalated quickly. More parties, more connections, more drugs. Acid, cocaine, mushrooms and ecstasy were all in the rotation.

“So from the ages of 15 to 17, I was pretty much doing anything and everything I could get my hands on,’’ she said.

Her parents knew something was off. They grounded her, a lot. Took away car privileges. They thought beer and marijuana were the lone culprits. But by that time, she had moved on heroin.

“I just remember they were terrified because they didn’t know what to do,” she said.

Good went to a detox center and given Suboxone, a medication to treat opioid addiction in adults.

The medication was working. She was sober for six months and moved into her own place. Then she met her neighbor. He sold heroin and cocaine for a living.

“So super bad luck there,’’ said Good. “Yeah, I ended up relapsing.”

Her parents wanted to put her back in rehab. She wanted no part of it. Her parents won. They sent her to Los Angeles.

“I called everybody that I knew to try to get a plane ticket back home,” she said. “Nobody would help me. Everybody knew I needed to be there. They were kind of sick of my sh*t."

“While I was there, I was really sick. I was in withdrawal. If you don’t know much about opiate withdrawal, you literally want to die. It’s horrific. And I wanted to do anything I could to get out.”

She met a fellow patient who said he had access to money and drugs in the state of Washington.

“So, I devoted every waking second to figure out how to get out of there,’’ she said.

She called her mother, lied to her about how terrible conditions were in Los Angeles. Told her she wanted to go to a treatment center in Washington, one away from the city and more like home.

The manipulation worked. Her mom purchased a plane ticket, and she walked out of rehab.

“I actually flew out there with this person who I had just met to get drugs,’’ she said.

That’s when things spiraled; the NARCAN saves from overdosing, getting beat up at drug deals, and seeing friends die.

“My parents had flown out there and had an intervention with me,” Good said. “My whole family flew out from Wisconsin to Washington and surprised me. And it’s just like you see on the TV show. They all read their letters. And I listened to them, and I refused to go to treatment even after that.”

And then she became pregnant.

****

Despite everything, her parents were there for her when she came back to Wisconsin.

When her mom showed her Kindle, there were only stories about addiction and books about recovery. And her mom told her about her many sleepless nights.

“The only time that she would sleep, she told me, is when she knew I was in jail,’’ said Good. “Because she knew I was safe. And one of the times when I was in jail, she actually wrote a letter to the judge out in Washington asking him to keep me in there so that she would know I was safe.”

She decided she would go to school and enrolled in the Substance Use Disorder Counseling program at Fox Valley Technical College.

“I would say the majority of the students have been at least affected by it in some way, whether it’s a family member, a friend, or themselves,’’ said Jeremiah Olson, the department chair. “And then a fair amount of the students are in recovery themselves and have gone through treatment, and do it because they want to pay back the help that they received."

“For somebody to say, ‘Hey, I screwed up, but my life’s not over. I’m gonna pull myself out of this and get back on track.’ It’s a great sign of resiliency, and her ability just to be successful in all of her improvements.”

Stephanie Good’s life has purpose now. She is eternally grateful for her family’s support. Yet she knows, deep down, she did this. Well, she and her son.

“I feel lucky to have had the support I’ve had through my family, because I know not everyone has that,” she said. “But I’m extremely proud of myself, and it doesn’t happen for a lot of people. I definitely feel lucky and God had a purpose for me and that’s why I’m still here doing what I’m doing."

“But I do credit my son for saving my life. Without my son, I do believe I would not be here today.”

Story idea? You can reach Mike Woods at 920-246-6321 or at: michael.t.woods1@charter.com