He was just a kid, sitting in the stands at the Brown County Fairgrounds, watching the racing car his dad built go around the track.

This, thought John Close, was simply the best thing ever.

But then came his first job after graduating from UW-Oshkosh. He was given an opportunity to document the state racing scene for the Capitol Times newspaper in Madison for $25 a story. This, thought John Close, was the greatest job anyone could have.

Until, of course, that time in 1986 when Close got to cover his first NASCAR race in Bristol, Tenn., an event won by Rusty Wallace, a driver he covered for many years in Wisconsin and whom he considered a friend.

“It’s still one of the best days I ever had at the racetrack,’’ said Close, a Manitowoc native. “As a kid, I never, ever dreamed that I’d get to do anything like that.’’

But then life changed gears again and, well, let’s face it, most of us never lay eyes on our childhood hero, much less meet them. But John Close? He worked for him.

“Every Tuesday he would come into my office and sit down and there he’d be across the desk from me, you know, in the hat and sunglasses and his bottle of Sun Drop,’’ Close said of Richard Petty, the king of NASCAR. “And, he’d want to know what was going on.’’

This was 1996 and Close was doing public relations and managing Petty’s NASCAR Craftsman Truck Series team. Absolutely nothing, thought John Close, could ever be better than this. How could it be?

Well, when Wisconsin’s Rich Bickle was in a pinch at the end of the 1995 Busch Series season and asked John Close if he could do him a favor, it got a whole lot better.

“It’s probably the only time I was ever scared,’’ said Close.

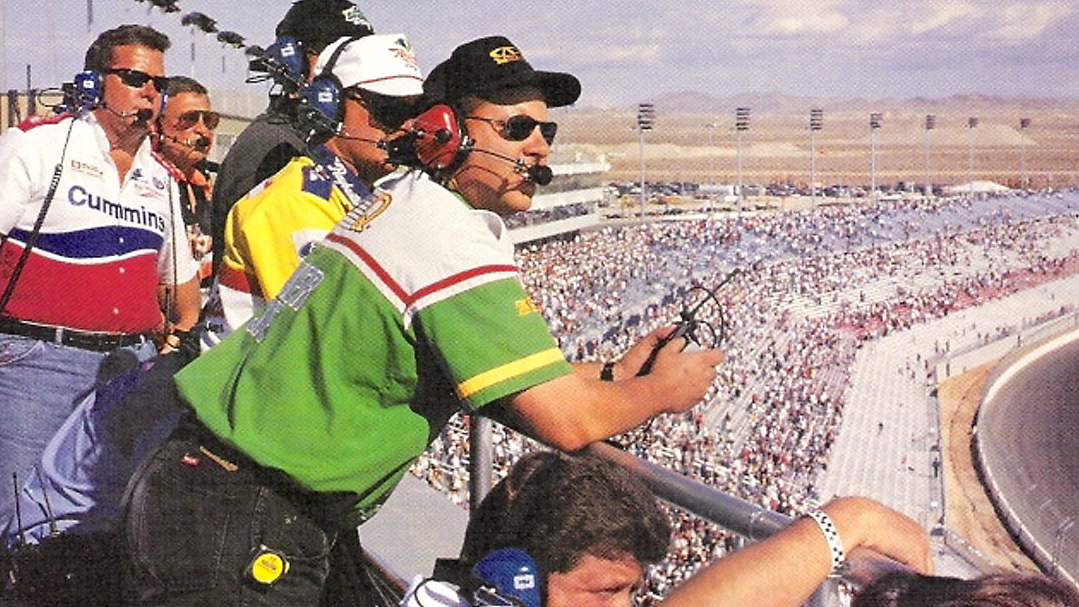

Bickle needed a spotter, the person who sits high above the track and relays vital information to the driver the entire race, keeping them alert of what is happening on the track and helping them steer clear of trouble.

It was a job Close had never done before and Bickle, in some form, was putting his life in Close’s hands.

“There’s just something about being up on that roof and it’s you and that driver against everybody else,’’ said Close, who helped Bickle to an 11th-place finish that day. “And yeah, the crew chief has a lot to do with it and the pit crew guys come out and they do their little 15 seconds of fun but, you know, it’s you and him for two-and-a-half, three hours, whatever it is. You know, it’s just more fun than you can have. It’s just the most fun I’ve ever had career-wise.’’

****

The biggest boost to John Close’s career happened his first day on the job, which also coincided with one of the worst days of his life.

He had moved to the “dark side”— which is how sportswriters at the time referred to the public relations profession — but the tradeoff was his paychecks would become plumper. It was Feb. 11, 1994, and Close was at Daytona International Speedway working for Cotter Communications and his new account, Bobby Labonte. But circumstances that day also had him looking after Neil Bonnett, whom he had become good friends while covering him during his short-track racing days in Wisconsin.

“So, literally, my first day on the job at the racetrack, I went to see Neil and told him that his rep wouldn’t be there and that I’d be handling things,’’ said Close. “And, we laughed and joked and had a great time and then, it was time for practice to start.’’

Just minutes later, Bonnett’s car crashed into the wall.

“I was at the infield care center, because that was the protocol as a PR person if your driver crashed,’’ said Close. “And they told me he had already been transported to Halifax Hospital. So we busted butt over there and Neil was already passed. He was gone.

“And so, my first day on the job as a newbie — nobody knew who I was — here I am at the hospital with a driver fatality. And in a very, very twisted, strange fate, by the end of that weekend, everybody knew who I was. And so, you know, my career got a boost from Neil’s passing because I went from nobody to someone everybody knew.

“And to this very day, it’s heartbreaking because Neil was the best man. He was just such a good guy and a great ambassador for racing. Unfortunately, racing has that dark side. There are fatalities and I couldn’t have had a more exacting lesson as to NASCAR public relations, especially in a crisis situation, than I got that first weekend. And that was something that throughout my career I drew on. So, at the time, it was very difficult, but looking back on it now it was, you know, you’ve got to make the best of it.’’

****

“Hey John. What is Dale Earnhardt really like?”

It’s a question, as both a writer and PR person, John Close would get often. Comes with the territory. But the reality is they don’t know. While they interact with them, rarely do they get a chance to know them. But they get glimpses.

“It’s pretty interesting because, you know, again, there’s perception and reality,’’ said Close of Earnhardt, NASCAR’s biggest star who died in a final-lap crash at the 2001 Daytona 500. “And the perception of Dale was ‘The Intimidator,’ this really hard veneer kind of guy who, on the racetrack was totally relentless. And I’m not saying he wasn’t that. But in private, he was very relaxed.’’

He recalled the time when actress Crystal Bernard, who appeared on the 1990s sitcom “Wings,” came to the track as part of a promotion. “Wings” was Earnhardt’s favorite TV show, and so his PR person came over and begged Close to bring her over to meet Earnhardt.

“And it was really interesting to see a guy who had all this adulation, all this fan love, if you will, just be completely on the other side of the fence,’’ said Close of Earnhardt. “And, you know, exhibiting that kind of behavior to her was probably the closest I ever got to see the real Dale Earnhardt.

“But Dale was great. I tell people this a lot, and they look at me kind of cockeyed sometimes, but the reality is, I believe Dale Earnhardt was way more important to NASCAR in death than he ever was when he was alive and on the racetrack."

“And by that, I mean, while he was a great champion, extremely accomplished driver, his passing made NASCAR really take a hard look at safety initiatives. Because if the best driver, the most accomplished, most skilled driver, could perish in a race car, there was something that needed to be fixed there.

"So from 2001 on, NASCAR started really implementing changes, not only to the race vehicles, but also to the actual equipment that the drivers wore, whether it was full-face helmets or the fire suits or the head and neck restraints. And I’m extremely happy to report that NASCAR to date has not had an on-track fatality since Dale Earnhardt. And I really believe that if his legacy is anything, it’s that. His passing spurred an era of safety conscious innovation that has benefited every driver, and fans and the sport since then.’’

****

In a career that spanned 40 years, John Close was a racing reporter, NASCAR PR professional, part of a NASCAR race day team for over 150 races, author of five books and also was a media coach for multiple NASCAR drivers, from a young Matt Kenseth to seven-time champion Jimmie Johnson.

“Racing is littered with drivers who had exceptional talent,’’ said Close, “but really had difficulty presenting themselves. And so they never ever got the opportunity to advance to the highest levels because they just were not able to project themselves in a positive way that would also be beneficial to secure big money marketing partners and pitching their products.’’

He also was part of a racing scene in Wisconsin that played such a vital part in NASCAR’s growth.

“Back in the 1970s and 80s, you had young stars, like Mark Martin and Rusty Wallace, who purposely came to Wisconsin to learn how to race from guys, like Dick Trickle and Tom Reffner, because those guys were the best there was at that time,’’ he said. “It wasn’t unusual to have Darrell Waltrip or Bobby Allison, Neil Bonnett and Dale Earnhardt; all those guys came and raced short-track cars up here.

“You know, later in my career, I can’t begin to tell you how many people - not only on a driver’s side, but crew chiefs, mechanics, media people - who apprenticed in Wisconsin and eventually got to NASCAR and other forms of national motorsports because Wisconsin racing is so epic.’’

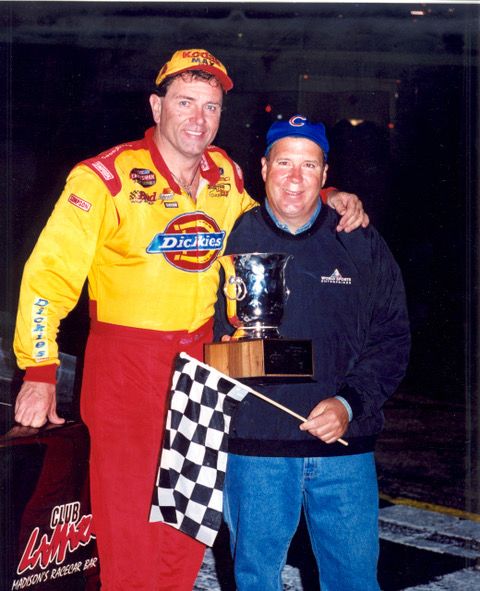

And it allowed him to not only cover the racing career of a legendary Wisconsin driver like Bickle, a guy who won a lot of races on the track and a lot of parties off it, it gave Bickle a chance to get to know Close.

And that’s how one day he tapped him on the shoulder and asked him to be his spotter, essentially putting his life into Close’s hands.

“He grew up around racing. He was just, you know, he wasn’t on the mechanical side of it, but he was a true racer in his heart,’’ Bickel said of Close. “And I mean, he’s super intelligent and super smart. I just thought, man, let’s give this a shot because we needed one and it worked out great.

“Actually, it was better than I thought it would be. Me and him, we’ve always been really good together.”

The ride has been memorable. If there is any regret, it’s that his dad, Lou, was not around to see his success, having passed away some 40 years ago.

“Not only did he introduce me to auto racing, and something that I have embraced and loved my entire life, but he’s still a great motivator to me,’’ said Close. “I can hear him all the time, you know? He had millions of sayings, and one of my favorites was, ‘You only need to know two things in life: The first is to believe in yourself and the second was to take a chance.’ And then there’d be a little pause, and he’d say, ‘If you take a chance, and it doesn’t work out, you still believe in yourself.’’’

And John Close always believed in John Close.

“I mean, I never anticipated writing and being a part of NASCAR; none of that stuff. It’s just amazing how life takes you in different directions. And if you if you apply yourself and you represent yourself well and you respect other people in the business, good things happen to you. I’ve been so fortunate to have more than my share of all of that.’’

Story idea? You can reach Mike Woods at 920-246-6321 or at Michael.t.woods1@charter.com