APPLETON, Wis. — Nathan Johnson remembers when his parents put the handcuffs on him.

Nathan is an avid esports spectator and video game player — emphasis on avid. But his parents leaned more heavily toward the "everything in moderation" philosophy.

What You Need To Know

- The total global esports audience was expected to grow to 495 million people in 2020, according to an annual report on the industry by Newzoo, an esports market research firm

- By the end of 2021, in the U.S., esports will have more viewers than every professional sports league except for the NFL, according to Activate, a management consulting firm for technology, internet, media and entertainment industries

- In 2019, the Overwatch Grand Finals was held at Philadelphia’s Wells Fargo Center and sold out a month before the competition

- Global esports revenue will grow to $1.1 billion in 2020, up 15.7% from 2019, Newzoo reports

“They’ve restricted me,’’ said the senior at Fox Valley Lutheran High School.

But then about three years ago, the administration at FVL decided to start an esports team and join the Wisconsin High School Esports Association (WHSEA), and the results were predictable.

“I jumped right in,’’ said Johnson.

“Ever since this has become an actual thing, (my parents) realize that this is a thing I can do and I can get stuff out of it. So they’ve been very supportive so far, which is nice.”

It wasn’t that long when we bickered back and forth about how hanging out with the Super Smash Brothers and some of their compatriots — Overwatch, Smite and Rocket League — were affecting our students’ academic performance.

But then some smart people realized that kids and video games are pretty much joined at the hip. A July study from the Entertainment Software Association said 76% of kids under 18 are gamers — and figured out that by giving the Super Smash Brothers a hall pass, it could actually lead to the development of a critically important educational tool.

“It’s not just that we’re playing games,’’ said Mike Dahle, the president of the Wisconsin High School Esports Association (WHSEA) and a business education teacher at Elkhorn High School. “It’s what playing the games is doing for the kids.

“And, ultimately, that is the first and foremost thing that our organization is; it’s all about enhancing and enriching the educational experience. We’re connecting it to curriculums, we’re building those connections and relationships with our students, giving them an environment where they feel safe and comfortable and accepted. So it’s a lot of those other things just beyond the games, too.”

****

WSHEA launched in 2017 after Dahle and a few other state high schools, who went around the Midwest to compete in tournaments, didn’t care for how things were being run and decided to start their own organization.

And, shocker, school districts across the state weren’t exactly lining up to join.

“In the first year, I emailed about 200 school districts across the state and I got seven, including my own,’’ said Dahle.

Today, there are roughly 75 state high schools participating. Word of mouth, an ever-present social media presence spearheaded by Dahle, and a group of WSHEA representatives making presentations at local education conferences have changed a lot of minds.

“This is organized team play,’’ Dahle says of the sales pitch. “There are career opportunities associated with it, there are ways to connect it with curriculum, there are colleges that are offering scholarships to recruit these players; it’s a lot of the underserved population within our student body.

“One of the big initiatives for most schools is to get all of our students involved in at least one club or organization within our buildings because we know that with student involvement, attendance rates will increase, grades will improve and disciplinary actions will go down. So we know that the research is there, that if we get them participating, it’s going to be a positive impact on our community.

“With the (esports) program at Elkhorn, I can speak accurately that for 90% of our students, it’s the only extracurricular that they participate in.”

These students are not only gaining social skills like teamwork, cooperation and collaboration, but many begin to explore fields like science, technology, engineering and math.

“About 54% of our students that participate (in esports) are pursuing STEM-related majors,’’ said Dahle.

****

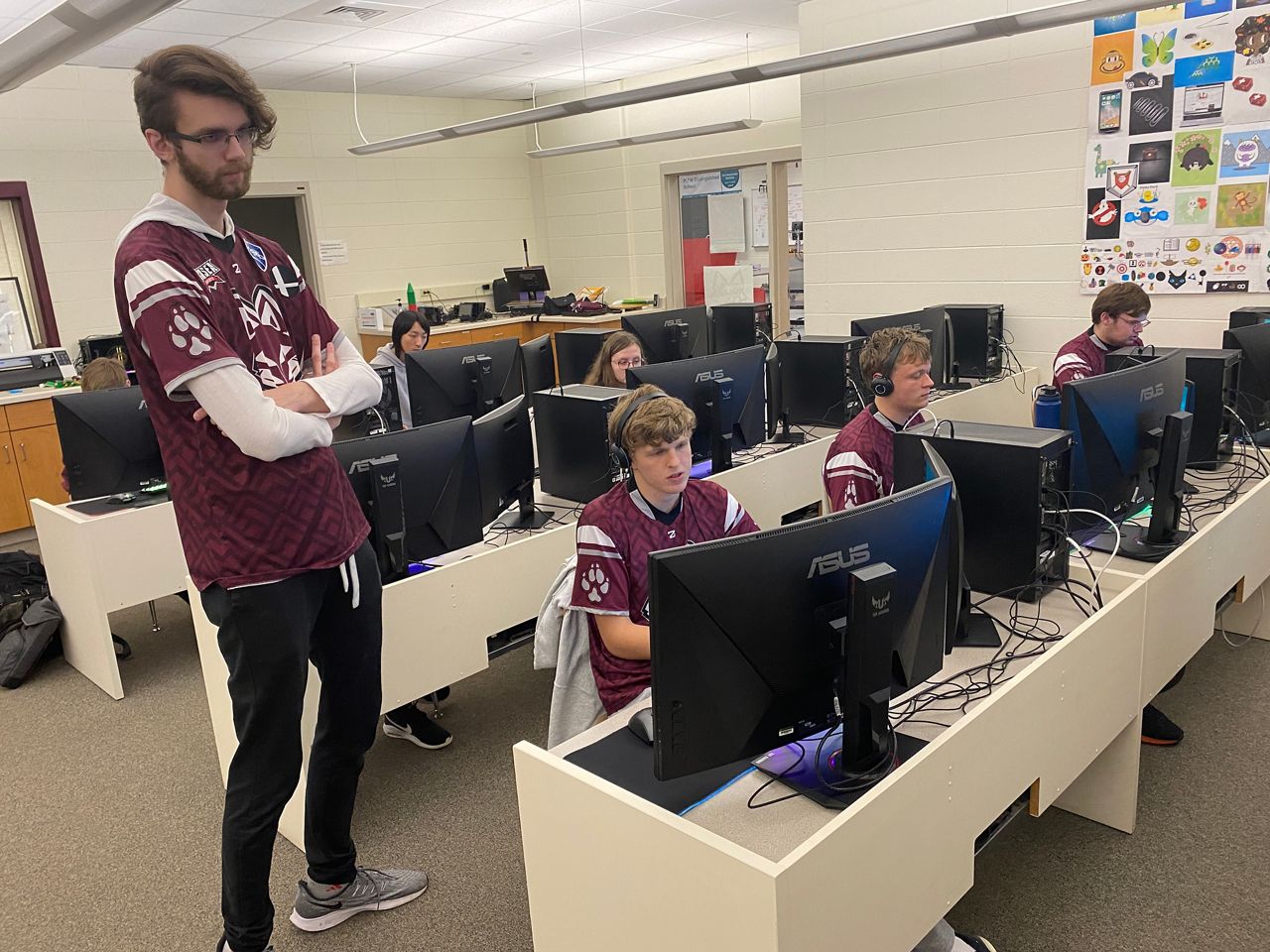

Nathan Johnson is a senior at Fox Valley Lutheran High School in Appleton and a co-captain of the Foxes’ esports team.

And when he found out FVL was going to sponsor an esports team, he couldn’t wait.

“I’m definitely more comfortable here than say other clubs because this is something I am passionate about,’’ he said. “So I’m just glad I have this opportunity to show that.”

He already has plans for college and wants to get into video game design, and says being a member of his esports team enables him to evaluate how certain games succeed, and also see their flaws. But, he says, that’s not the best part of being part of the FVL team.

“That I get to play video games with other people that I know,’’ he said. “Not just online people. I know them in high school and I can play with them and do stuff outside of school with them as well. I think that’s probably the best thing.”

Nathan Nolte oversees the FVL program and acknowledges there was some healthy skepticism among parents when the program was introduced.

“The first reaction of some people will be, ‘Oh, really, kids get to play video games in school?’” Nolte said.

“But I tell parents, one of the twists this puts on it is, now that this is their sport, their co-curricular, they have to follow the same training rules and the same eligibility requirements as any other athlete or sport. So, yes, they have to practice, but if they’re not doing their homework, they can become ineligible and they don’t get to participate. I think that’s provided a nice motivation for some students. Some students who I’ve had, who have maybe struggled with academics and homework wasn’t a priority, are like, ‘Oh, I don’t get to do this if I don’t get my stuff done? OK, I’ll get my stuff done so I can do this.’

“Plus it’s been a great recruitment tool for our admissions department; they get a lot of middle schools kids that say ‘Oh, you get to do esports?’’’

While there is not a suitable setup for parents and friends to watch matches live, they can view them through the WSHEA Twitch Channel.

And doing the play-by-play for some of those matches is Jason Schlaver, a 2020 FVL graduate who is also serving as an assistant coach for the FVL team.

This is a growth industry. According to Newzoo, the leading global provider of esports analytics, it will surpass $1 billion in revenue for the first time this year and projects $1.8 billion in 2022. Also, viewership is expected to be higher than every U.S. professional sports league, save for the NFL, this year.

“I’m looking to go full-time in it,’’ said Schlaver, “which is a little bit different than one might think.”

He has no professional training but instead is learning by watching others and hustling for work.

“One of the biggest things is getting out there and finding these smaller tournaments and trying to be like, ‘Hey, I want to broadcast this game,’’’ he said. “And just try and build up your community and try and build up a portfolio and once you do that, people will start to take notice.

“This is all game knowledge, this is all my taking notes from the professionals that do this for a living, this is just me learning to become one by myself. It’s been fun, it’s been a fun journey.”

****

While school budgets are seemingly always tight, esports is an affordable addition.

With schools using their own computers and computer labs, and with no travel except for the two WHSEA state tournaments a year — one in winter and one in spring — Dahle says it only costs his school about $100 a year to field all their esports teams.

In terms of value, it’s nearly impossible to beat the cost, it is invaluable to be able to offer an underserved part of the student body the opportunity to have the same high school experiences as their peers, and the return on a school’s investment is undeniable.

“We’ve got a few students who do other sports and other activities as well,’’ said Nolte, “but for the most part, this is what a lot of them have found that this is what they want to do. And this is what they put their time and energy in to, and it gives them school pride, a sense of belonging, a sense of how they can contribute.

“We do things where they can get jerseys and things like that. Why? Because it gives them that sense of team, gives them that sense of what they’re contributing to the school, they get recognized at the pep rally for Homecoming; all that.”

Story idea? You can reach Mike Woods at 920-246-6321 or at: michael.t.woods@charter.com