Editor's Note: Caution advised. Some details in this story may be disturbing to readers.

Gabriel Schauf was going to be an actor on Broadway, or become part of the cast of Saturday Night Live.

That was the plan when he went off to the University of Minnesota to become a theater major.

And then, life happened.

Today, Gabriel Schauf plans funerals.

“This is an amazing profession,’’ Schauf said. “I think, when people here mortician or undertaker or embalmer, those buzz words, people flinch. ‘That’s a job? Who would want to sign up for that?’ I’ve met people and they go, ‘What do you do for a living?’ I say, ‘I’m a funeral director.’ And I’ve actually had people go, ‘Oh, I’m sorry.’

“It’s like, ‘I didn’t get tricked into this.’ It’s actually a really cool job.’’

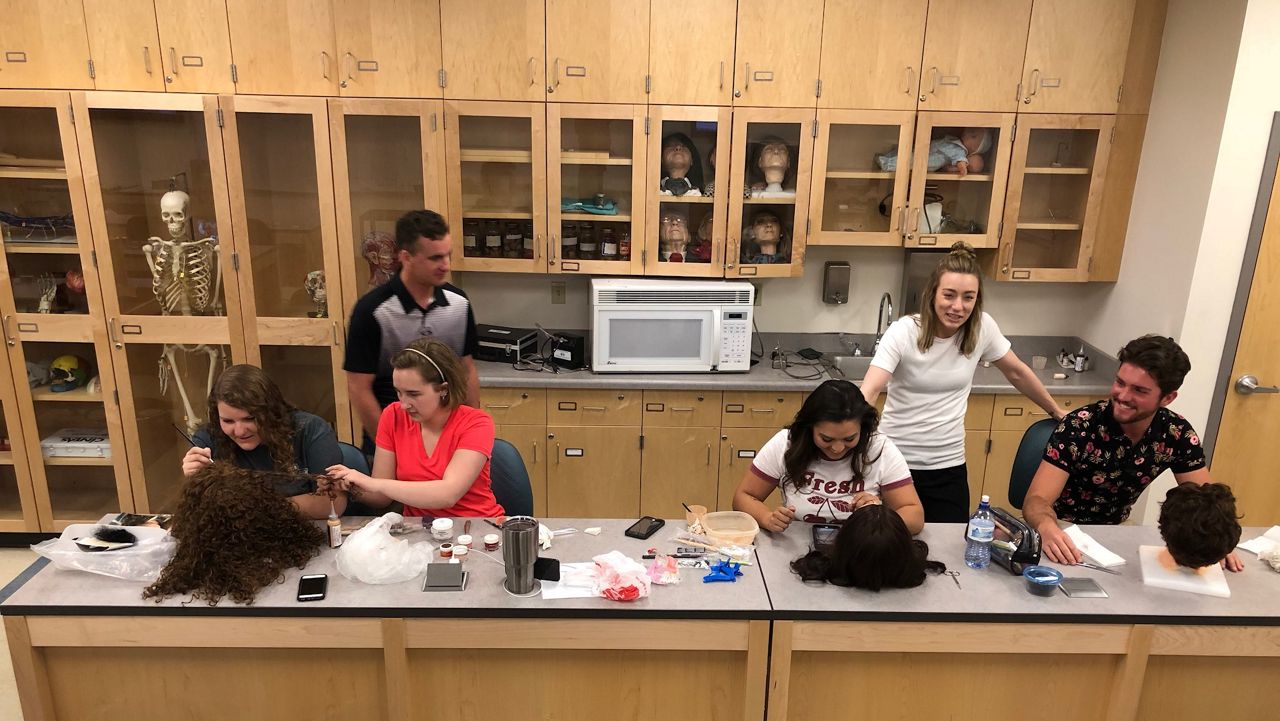

Part of Schauf’s job now is teaching those who want to become funeral directors — yes, people do really want to do that — at Milwaukee Area Technical College.

It’s a growing program that through an articulation agreement — an official guarantee that classes completed at one school will be accepted when a student transfers to another school — is being expanded to include Fox Valley, Gateway, Blackhawk and Chippewa Valley technical colleges.

The idea of this being more or less just a family business is, well, dying.

“We do have a lot of non-traditional students as well,’’ Schauf said. “We see a steady flow of traffic of maybe former military personnel, emergency medical personnel, firefighters, we’ve had some police officers come through, second-career students who kind of — again, may have considered this or looked at it as an option — and then just kind of found that right time to do it.’’

****

The program is growing as well because of a series of changes that have made it more viable to fit into a two-year associate’s degree.

Schauf said two years ago the Wisconsin State Legislature agreed to eliminate some credits in the state statutes that were deemed unnecessary, which reduced the number of credits required from 93 to 64.

Also, to be qualified by the state, students must serve a year’s apprenticeship. So in 2018, the Wisconsin State Examining Board for Funeral Directors worked with the state legislature to change the requirement for becoming a funeral director’s apprentice to a two-day, 16-hour course. Previously, students had to have 28 college credits before they could qualify.

“The job market is really good,’’ said Schauf. “I don’t know the exact numbers but I do know funeral homes are looking. Especially with the baby boomers coming through, the calls are increasing.”

In the articulation agreement, students from around the state can complete their general courses for the program at their local technical college, then do their technical work with MATC before they take the required national board exam.

“The nice thing there is students can stay in their area if they’re working for a funeral home in that area,’’ said Schauf. “They can continue to work for that funeral home, which is a very important aspect to this and get all their education.’’

Important because, let’s face it, working on a dead body is not a natural thing to do.

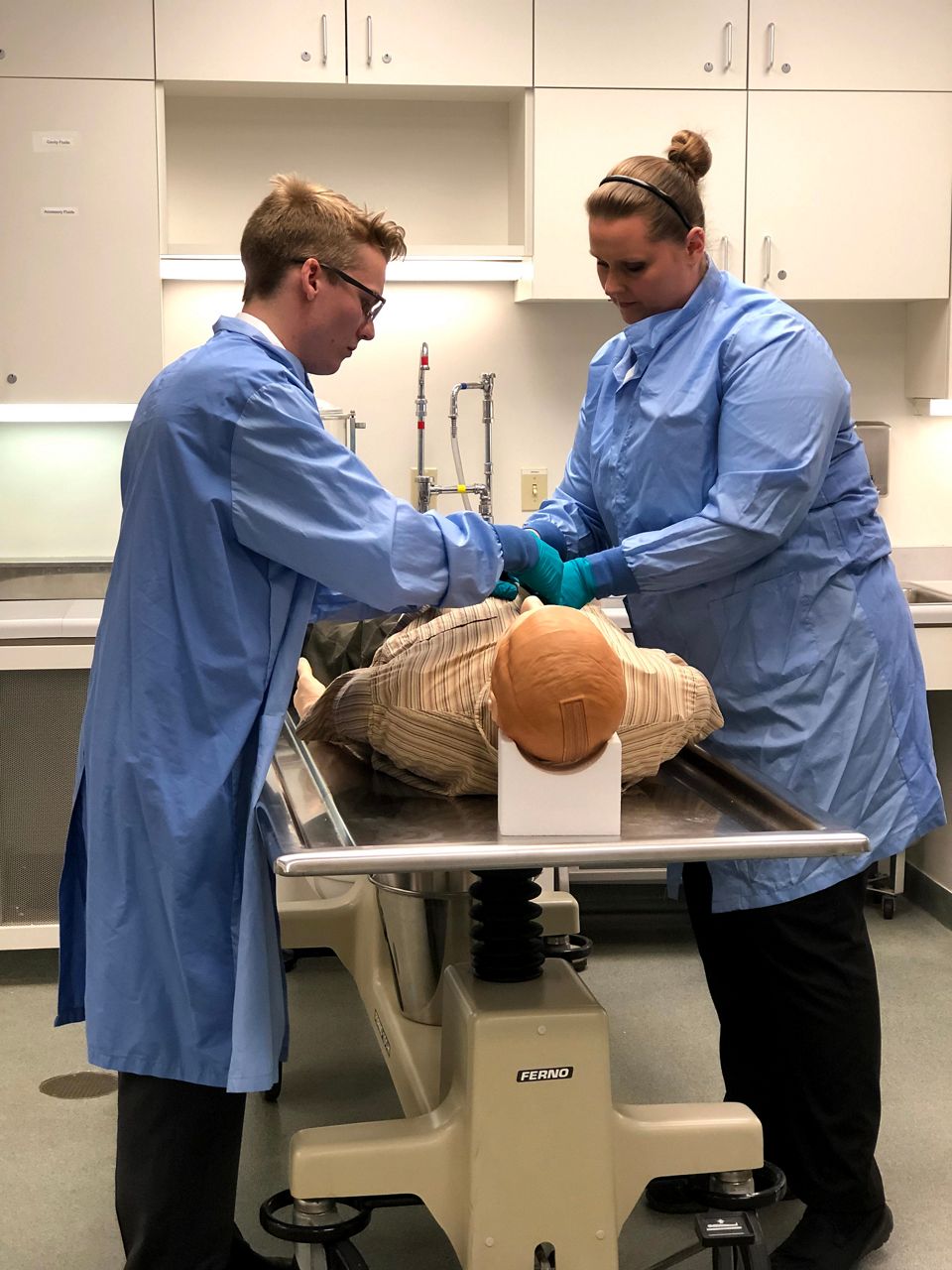

“So many of them have been working at a funeral home, even for a few months,’’ said Schauf. “They’re getting that experience. We do occasionally get some folks who just haven’t done that part yet, we’ll say, and yeah, it is interesting. You have to ease them into it. You try your best to explain to them what they’re about to see, you’ve got to talk about the condition of the body — it is baby steps.’’

The school has a relationship with the Milwaukee County Medical Examiner’s office, as well as some local funeral homes in the area — for families who wish to donate organs or tissues — who provide cadavers for the students to work with.

In the case of the medical examiner’s office, many of the bodies provided are abandoned or unclaimed.

“With those bodies, we take them into our care, our students work with them, they embalm them,’’ said Schauf. “Of course we’re there supervising. We’re there teaching, educating. The students are getting a great experience with that. We have clothes that are donated so the bodies are dressed. They’re casketed. They’re taken care of. There’s a certain care and respect given to that individual, and then they complete that burial process. At least this way, it’s kind of a win-win-win. The bodies are getting cared for, appropriately being attended to — the way anybody deserves — and the students are getting a great experience in that as well.

“That’s one of the nice things about having this lab, and the opportunity to do embalming as part of the program, is that students have time to acclimate themselves and learn these techniques safely and to standard. It’s just a good opportunity to get them comfortable with the situation.’’

****

Kyle Grant took the job as a part-time gig in college because the business owner was a family friend who needed help.

The business was the Wilson Funeral Home in Racine and part of Grant’s job was to “pick up people from places.”

“Some of my family and friends were weirded out by it,’’ he said. “Right away they were going, ‘Oh my gosh, you’re going to pick up dead people?’ And I said, ‘I hate to say it that way but, essentially, yes.’ But that’s not everything this job is.’’

Grant was attending UW-Parkside and earned his degree in criminal justice. He was equipped with an abundance of caring genes and wanted a profession where he could help people. Initially, he thought that would be as a parole officer. But working at the funeral home changed his mind.

“I kind of started to think, ‘Well, maybe I’m more supposed to help people get through death,’" he said. "‘Maybe I’m more compassionate that way.’’’“I kind of started to think, ‘Well, maybe I’m more supposed to help people get through death,’" he said. "‘Maybe I’m more compassionate that way.’’’

He leans on the words of his old teacher, Gabe Schauf, to explain how that works.

“He says, ‘You’re more caring for the living family as funeral directors,’’’ said Grant.

“I would say even more of my job is working with the living family and caring for them and getting them through this most difficult time in their life.’’

It’s not normal to have to process death on a daily basis. There is a lot of stress, a lot of sadness. And when you start out, it can stop you in your tracks.

“You know, I remember the first time I saw a dead person,” Grant said. “Growing up, I was going to funerals when I was a kid, and I did see the open casket body and that’s when they’re all prepared and look nice, so that’s one thing.

)

“I remember when I first went on a house call with my boss, when I first got hired here five years ago, I remember seeing the lady that we were going to pick up, and it was an older lady and her mouth and her eyes were wide open, and that freaked me out. For a second there, that was a shock of reality, you know, that this is what death really looks like when it’s not prepared, makeup, open casket, nice funeral setting; like this is really what death is about.’’

To ensure his job doesn’t become overwhelming, Grant said he makes sure he keeps up with his hobbies of music and baseball and relies on a solid support system.

“Most aspects of this job I’ve figured out a way to kind of just get through it, or just kind of how to process it,’’ Grant said. “Whether it’s a death from overdose or death from suicide, anything like that. But when it comes to children, I don’t think that’s something I’ll truly ever know how to get through. I hate it when I see children die. I hate it when I see anybody die, but when we get calls and we get a baby or get a child, that’s when it’s really hard.’’

It may not be a desired profession for the masses, but it’s a job someone has to do.

“They (friends and family) look up to me for what I do,’’ he said, “helping people through this time. So just having a great support system and knowing that you’re doing good and making a difference in people’s lives, that really helps me get through my days as a funeral director.’’

****

The look of a funeral has continued to evolve, as families are looking beyond a church, a casket and a few verses of “Amazing Grace” to celebrate their loved one’s life.

“We’ve really become a profession of event planners,’’ said Schauf. “We create these cool, elaborate services that are based on telling that person’s life story. I’ve done services at golf courses. You know, we all meet, you golf nine holes, everybody meets at the 18th hole at the end, you do a little prayer service and you all take a shot and that could be a funeral. Host a poker tournament; that could be a funeral. Go fishing at grandpa’s favorite lake, meet in the middle of the lake after a morning of fishing and scatter some of the cremated remains in the lake and say some prayers, that can be a funeral.

“And people don’t realize they could do that. Being able to offer that to families and say, 'Hey, let’s send this person off right.' I think that’s an amazing opportunity that we have.’’