Here in America, it was Benjamin Franklin's key and kite experiment involving lightning and electricity that many of us remember learning about in school. But Franklin's meteorological discoveries went well beyond what our elementary school textbooks details.

What You Need To Know

- Benjamin Franklin discovered many modern meteorological concepts

- He correctly hypothesized the flow and movement of storms

- His kite experiment proved that lightning was indeed electricity

- Many of his discoveries are used in modern meteorology today

One of the most exciting aspects of being a meteorologist is the ability to not only study a phenomenon that affects literally everything and everyone, but using new and exciting technology to do it. New radars, applications, and advancements all keep us looking toward the future as we continue to improve and evolve everyday.

But sometimes it's fun to look back -- way back, to when scientists first started discovering how to forecast the weather. Although technology was either primitive or non-existent, we can oftentimes learn some great lessons from those who were pioneers in the field.

The study of weather can be traced all the way back to nearly 3000 B.C., when observers in India wrote about cloud observations and the water cycle. Fast forward to 350 B.C., to when the Greek philosopher Aristotle wrote Meteorology, the first real compilation of meteorological studies, terms and collective observations.

In many ways, Benjamin Franklin was America's first national meteorologist.

It's widely known that Franklin took part in multiple transatlantic crossings. In fact, it was during these travels in the 1720s that he observed the water temperatures of different points in the ocean. Whenever he crossed the Gulf Stream, he noted how the temperatures were in some cases over 20 degrees warmer than areas out and away from the coast.

Not only did the better understanding of the currents help Franklin suggest using that flow to help improve the speed of ships, but the discovery of that warm ocean current allowed meteorologists to help track and predict the movements of hurricanes -- something we all use today.

In late October 1743, Franklin was excited to view a lunar eclipse. As an experienced astronomer, he set himself up to view it from his home in Philadelphia, and was eager to contrast it with how it looked in Boston, where his brother (1 of 9 siblings) lived.

Unfortunately, it did not turn out great, as clouds, rain and brisk winds kicked up, blocking the view of the event. With Boston in the northeast, Franklin assumed his brother also experienced the same weather.

But when the notes arrived from Boston, an interesting observation was made: his brother had seen the eclipse, detailing the event, but noted that afterward, the weather turned nasty with northeast winds, clouds and heavy rain (most likely a nor'easter).

This not only intrigued the scientist, but inspired him to set out and gather more observations between Philadelphia and Boston, leading him to document for the first time, the movement of storm systems in the northern hemisphere.

After years of studying the destruction and damage this storm (and others after it) left behind, Franklin correctly determined that storms do not always travel in the direction of prevailing wind, and that the surface winds of a storm system were only incidental to the forward movement of the storm.

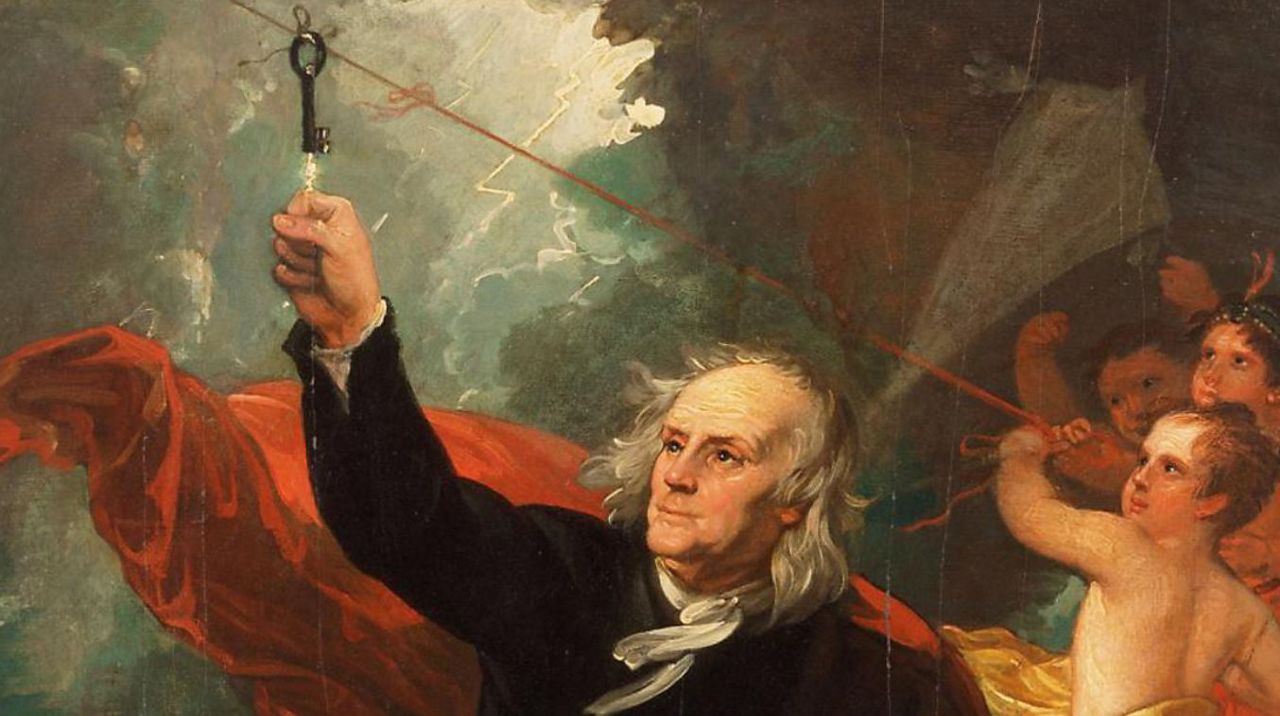

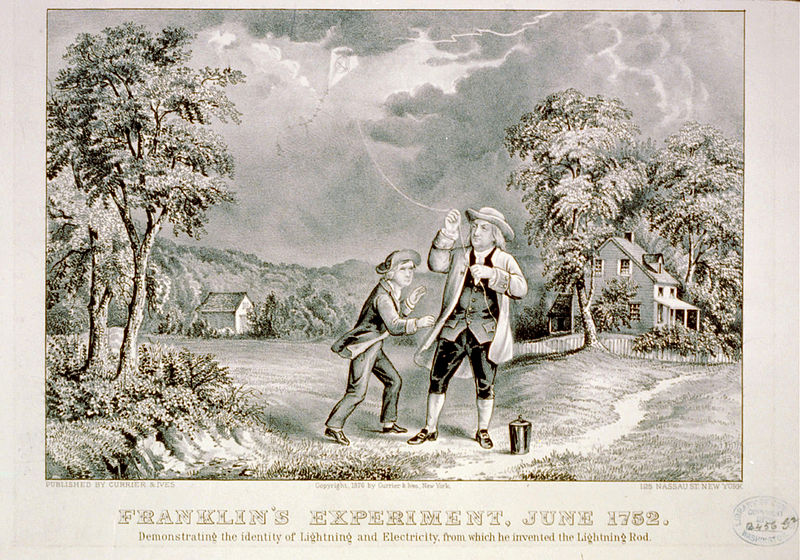

Nine years later in 1752, Franklin's famous kite and key experiment took place. The kite was NOT struck by lightning (Franklin would have been electrocuted) but instead, picked up the electrical charge from the storm.

He knew the dangers, but set up the experiment in such a way to have the kite collect electric charge from the cloud, proving lightning was indeed electricity. Interestingly and sadly, just a month later a Baltic scientist by the name of Georg Wilhelm Richmann attempted a similar experiment without using those precautions and was killed after being struck.

Franklin was fascinated with weather and climate his entire life. Just six years before his death, he published a number of "Meteorological Imaginations and Conjectures." He was one of the first people to question why we would see hail in the summertime.

He correctly deduced that the upper atmosphere was much colder than the air below it. Moist air flowing into the upper atmosphere could produce ice that could fall to earth before it melted. These hypotheses later became meteorological facts.

Before his death in 1790, Franklin also correctly identified weather phenomena including heat radiation, fog and wind direction.

While there have been numerous advancements in technology and science when it comes to meteorology, no other early American scientist even comes close to Benjamin Franklin -- a man whose concepts and discoveries we meteorologists still use today!