WASHINGTON, D.C. — Even as prescription drug costs have skyrocketed in recent years, Hart Pharmacy in Cincinnati is getting less money per prescription, costing the pharmacy tens of thousands of dollars each year. Third-generation pharmacist and owner Sarah Priestly said costs associated with PBMs forced her to cut back hours for her staff of 16.

“For now, we’re OK, but we’re making harder decisions than we’ve ever had to,” Priestly said.

Pharmacy benefit managers, or PBMs, are companies that control access to prescription drugs by negotiating drug prices with drugmakers and deciding how much insurers pay pharmacies for medicines and services.

PBMs have become an integral but poorly understood component of the American health care system.

What You Need To Know

- Pharmacy benefit managers, or PBMs, play a large role in the American health care system

- A growing chorus of pharmacists, patients and lawmakers claim PBMs seek to maximize their own profits rather than drive down health care costs

- Congress and the Ohio Attorney General are taking measures to enact stricter PBM regulations

They were designed to bring down health care costs. Drugmakers want their drugs listed on PBMs’ formularies, which determine which drugs are covered by insurance. Pharmacies want to be listed in-network, which gives them access to more patients. In exchange, both agree to offer discount on drug prices.

A growing chorus of pharmacists, patients and lawmakers claim PBMs instead seek to maximize their own profits.

Ohio Attorney General Dave Yost said he gets several calls a week from patients and independent pharmacists struggling due to PBM policies.

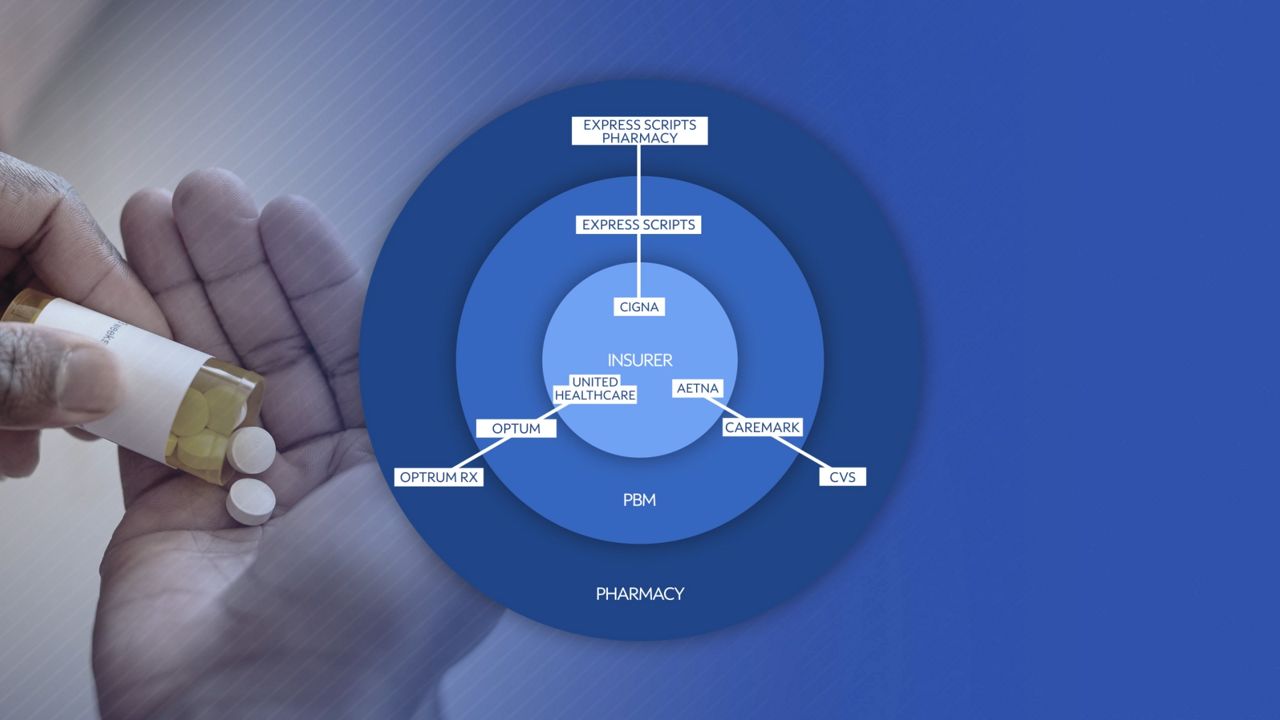

The heart of the issue, Yost said, was the market dominance of three major PBMs: CVS Caremark, Express Scripts and Optum. Together, the three hold 79% of market share.

All three companies are linked to their own respective insurance company and retail or online pharmacy.

This concentrated influence has allowed PBMs to increase their profits at the expense of patients and independent pharmacies, Yost alleged.

“It’s like an old river in an industrial city. Every year after year after decade after decade there’s more sediment, there’s gunk that went into the river that sinks down on the bottom. Pretty soon all you’ve got left is gunk and hardly any water. The only way to fix it is to dredge it out and start over. That’s where we are with our healthcare system when it comes to PBMs,” Yost said. “They are adding complications and burdens to the system that are adding no value and driving prices up.”

Yost filed a lawsuit in 2023 against seven PBMs, included Express Scripts, for allegedly price fixing prescription drugs via a Swiss company.

“In our lawsuit, we accuse them of sharing information overseas amongst themselves that is actually having an anti-competitive impact here in America,” Yost said.

The case is currently in legal limbo after the PBMs sought to move the case from state court to federal court, then get it dismissed. In January a U.S. District Court judge denied the motion to dismiss and moved the case back to state court. The defendants appealed the ruling to the U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals, where no hearing has yet been scheduled.

Yost soon tried another tactic to rein in what he calls the “nefarious tactics” of PBMs. On Feb. 20 he led a coalition of 39 attorneys general calling for stricter federal PBM regulations.

The letter urged Congress to act on several pieces of legislation that would require more transparency in PBM transactions, delink PBM fees from drug prices and ban PMBs from compensating certain pharmacies differently for the same drugs, among other measures.

Several of those measures cleared two Senate committees to be included in the 2024 federal budget appropriations bills, but disagreement between House and Senate Republicans on the scope of the measures led to them getting sidelined, likely until a lame duck session after the November elections.

Rep. Greg Landsman, D-Ohio, is working on a more modest bill that he believes can pass more quickly with bipartisan support. The Medicare PBM Accountability Act targets spread pricing, in which PBMs charge insurers a higher amount for a drug than is reimbursed to the pharmacy. The bill would require PBMs to disclose the profit they make on prescription drugs for seniors.

“It requires the kind of transparency that anyone would expect,” Landsman said. “So that when you are buying and selling prescription drugs and you’re putting it on the market, are you getting kickbacks? Are you seeing savings and are you passing those on to shareholders as opposed to seniors? And if you are, we’ve got to put an end to it.”

PBMs are pushing back against stricter regulations. The industry group Pharmaceutical Care Management Association (PCMA) spent $15.4 million on lobbying last year.

Landsman said he was not deterred by industry pressure.

“The TV commercials get me even more determined to get this done because if you have that kind of money—millions and millions of dollars to spend on TV commercials—that means you could be passing on those savings,” Landsman said.

Express Scripts and Optum did not respond to a request for comment on allegations made in this story. CVS Caremark referred the request for comment to PCMA, which did not respond.