CINCINNATI — Mayra Tafoya is a self-described foodie. She enrolled in the culinary arts program at Cincinnati State Technical and Community College in 2019 with the goal of someday opening a restaurant to pay tribute to her Hispanic heritage.

But now, Tafoya no longer sees herself running a kitchen of her own.

It’s not that her love of food has changed or that the program dampened her ambitions for finding a career in the industry. It’s actually just the opposite. The 24-year-old said her appreciation for food has only grown over the past four years.

Her time in Cincinnati State’s Culinary and Food Science program showed her there are more professional opportunities to showcase her love for food than she ever imagined.

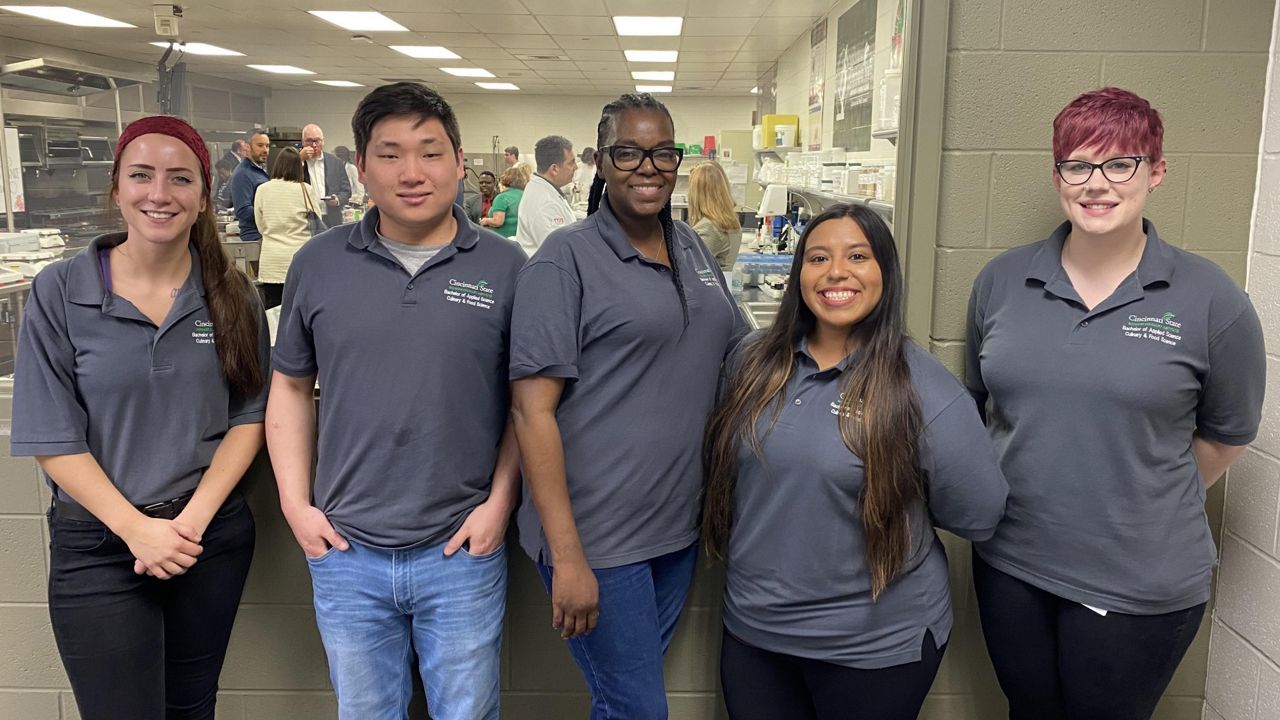

On May 7, Tafoya and nine members of her cohort will become the first-ever graduates of the program.

What You Need To Know

- The first cohort of Cincinnati State's Culinary and Food Science bachelor's program graduate this May

- The program teaches chefs the science behind food to help them find food industry jobs outside the kitchen

- Ohio's food and agriculture industry is a $124 billion business

The program aims to prepare students for entry-level food scientist and technologist positions in the food, beverage, or flavor industries. The graduates’ newly honed skills could lead them to careers in research and development, quality control or even specialty ingredient sales.

For some students, the courses just taught them the chemistry needed to unlock the flavors in ingredients and make them a better chef.

Tafoya is starting a full-time job with Perfetti Van Melle — a Dutch-Italian multinational company of confectionery and gum — after graduation.

“I thought I had to own my own businesses to do something in the food business. But I’ve learned I can do something amazing, have fun doing something new with every day even if I’m not always cooking,” she said.

The Cincinnati native joked about being intimidated by the prospect of opening her own eatery. She also didn’t know if working long hours in someone else’s kitchen was the professional path she wanted to take.

“This program gave me a chance to develop a career in this industry that allows me to balance life at work and home while still being able to express my love for food,” Tafoya added.

Creating a program from scratch

Students focus on fundamentals of culinary arts for their first two years. They work out of the state-of-the-art culinary and baking laboratories at the highly regarded Midwest Culinary Institute on Cincinnati State’s Clifton campus.

Upper-level coursework includes food ingredient functionality, food product design and development, sensory evaluation and testing, food microbiology, and other preparation for professional careers. They use equipment such as PH meters and a viscometer to best understand properties of food such as acidity and consistency.

Grace Yek, who developed the bachelor’s degree tract, described it as a “rigorous applied science program” that’s “very hands-on and industry aware.” She noted that when students complete their coursework, they’ll have a “precise yet intuitive approach to food.”

Yek, a classically trained chef and a chemical engineer, stressed that there’s a lot more math and chemistry that culinary school.

Pastry chef Kiara Daniels, 27, compared baking to science and math because of the emphasis on precise measurements and knowing how ingredients work together. But she never knew “why” certain things behaved the way they did. She gave an example of the molecular differences between baking powder and baking soda.

Those insights have helped her become a better baker, Daniels said.

“Whether they’re cooking a kitchen or working in a lab, our students are ready for either environment because they understand how food works at the molecular level,” Yek said.

The program prepared Matthew Schmitt to take his passion for food to “the next level,” he said. The 23-year-old currently works as chef for Avril-Bleh Meat Market and Deli. He’s said he hopes to land a job at a regional food manufacturer in the next few weeks.

Schmitt enrolled at Cincinnati State with every intention of becoming a chef. But Yek approached him early on to let him know the program was in development and he and other students would be able to “roll right into the program” when they finished their associate degree, he said.

That’s just what they did. The inaugural class is graduating a full year earlier than projected.

Nicole Hatfield, who’s also graduating in May, said she entered culinary school with a very farm-to-table mindset that emphasized fresh ingredients. It was easy to “turn my nose away from consumer-packaged goods,” she said.

The last two years have taught her to appreciate the technical aspects of creating packaged ingredients and the processing that goes into it. One food mentioned during the event was guacamole. Home-made guac can turn brown in a matter of minutes, but by employing a process called high-pressure pasteurization, guacamole can be kept safe, colorful, and great tasting for weeks.

Not all members of the Culinary and Food Science staff have worked in a kitchen. One example is Karen DeWitt. After earning a degree in food science, she spent her entire career working in other areas of the food industry. DeWitt spent 34 years in food ingredient sales. Now retired, DeWitt teaches ingredient functionality and formulation, the student’s introductory class out of culinary school. She refers to it as their "introduction to industrial world.” She also leads the product development class.

“Here, you’ve got major flavor houses, meat manufactures, a major grocery company with its own product development lab. So, in Cincinnati, you can go about anywhere,” DeWitt added.

Helping young chefs make some major ‘dough’ after college

The Culinary and Food Science program is one of the few applied bachelor’s degree programs offered at Cincinnati State. The school is going to offer a nursing program this fall.

The Ohio General Assembly and the state’s Department of Higher Education allowed community colleges to offer bachelor’s in 2017. They did so to help address workforce shortages in particular fields in Ohio.

One of those industries is food and agricultural. It has an estimated economic impact of $124 billion every year, according to information from JobsOhio. There are more than 1,400 food manufacturers throughout the state.

A community college can only offer these programs if there’s isn’t one like it at a nearby university. The University of Cincinnati offered a food science program in the past. The school recruited Cincinnati State culinary arts graduates. That program ended in 2013-14.

Now, the closest program is at The Ohio State University in Columbus.

Dr. Monica Posey, president of Cincinnati State, said that one of the college’s chief goals is to “meet the needs of our regional workforce.” These programs do that by preparing students for well-paid, in-demand jobs that have a strong future potential, she said.

Even though commencement isn’t for another week, each of the Culinary and Food Science seniors has lined up a job or is completing co-ops, according to Cincinnati State. Some of those include the likes of Givaudan, Samuel Adams Boston Brewery, JTM, Flavor Producers and Archer Daniels Midland, also known as ADM.

Another of those companies is SugarCreek, a Blue Ash-based food manufacturer. It has six plants in the Midwest and annual sales of more than $1 billion.

Zach Shepard, director of culinary sales for SugarCreek, called the Cincinnati State program “invaluable” as it adds much needed highly trained talent in a field that needs it.

“Many of the companies where our graduates will work are at the forefront of innovation, bringing to market exciting global flavors, and minimally processed, healthy, fresh-tasting foods,” Yek added.

The traditional route is for students to study all four years at Cincinnati State. But Yek said there are “several entry points” to the program. One of the 60 current students in the program is a graduate of the school’s brewing degree tract.

Yek advised prospective students to reach out to her to discuss next steps.

As for Tafoya, she’s happy that her time at Cincinnati State is wrapping up. She, like her classmates, praised Yek, DeWitt and other professors for setting them on a stage of success.

One day, she hopes to see a product she helped create on the shelves of grocery stores across the country.

“Now, I have another way I can express my love for food and represent my Hispanic heritage,” she said.