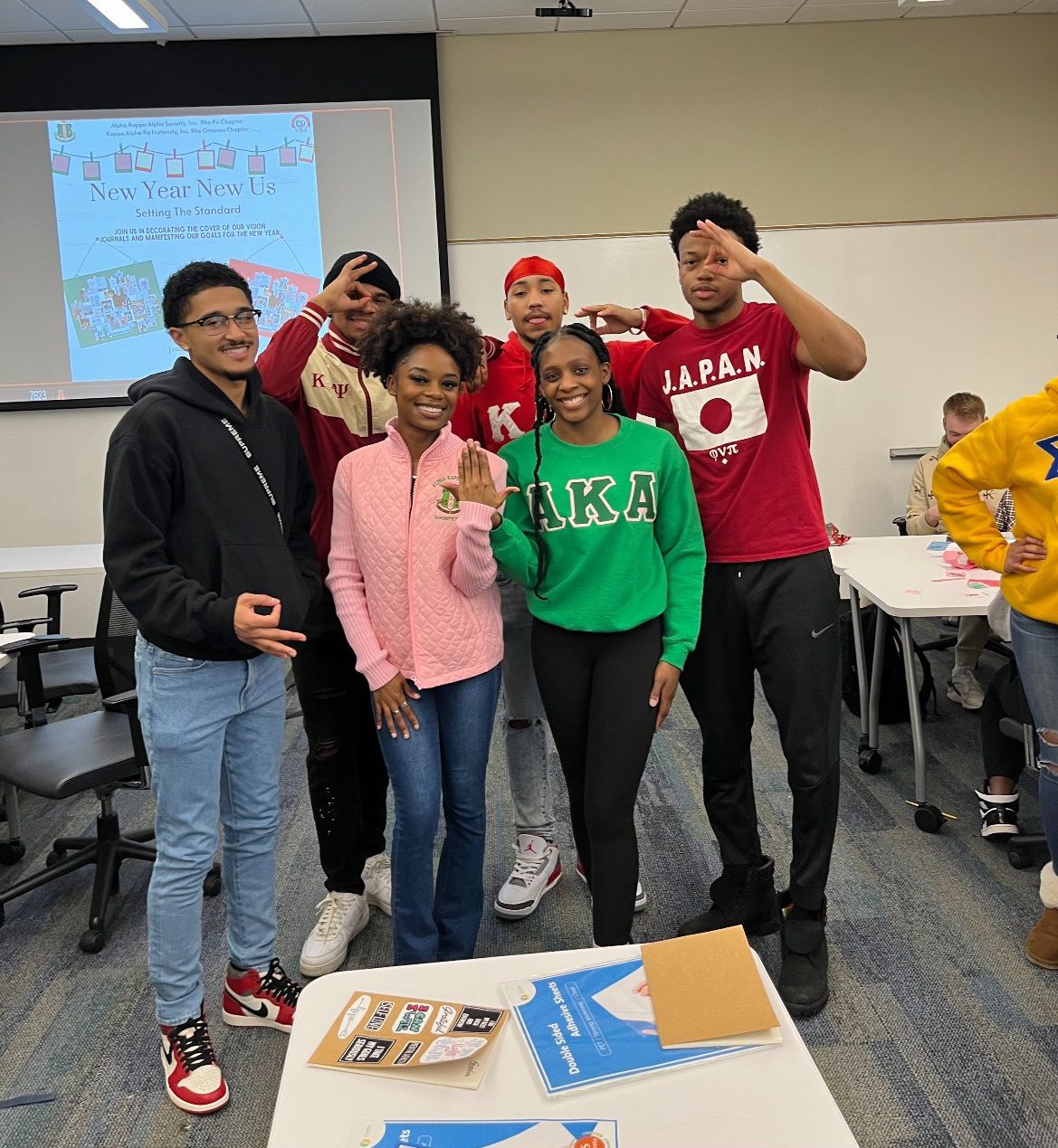

CINCINNATI — Xavier University student Shanna Turner credits her nearly two years as a member of the Alpha Kappa Alpha Sorority, Inc. with empowering her to reach “further and dream bigger” than she ever thought possible.

The senior is a member of the organization’s Rho Psi chapter. Turner is also the campus president of the National Pan-Hellenic Council, often called the “Divine Nine.” It’s the umbrella organization for the nine historical Black fraternities and sororities on college campuses nationwide.

“They made me feel at home right away,” the 22-year-old African American said of the group of sorority members she met when she arrived on campus.

What You Need To Know

- For more than a century, Black fraternities and sororities have offered safe spaces for students to learn and grow at colleges across the country

- Beyond providing educational support, the organizations aim to address social injustices on and off campus

- A huge part of Black Greek life is creating a lifelong social network with fraternity brothers and sorority sisters of all ages

Because she’s a first-generation college student, Turner admitted not knowing about the Divine Nine when applying to colleges.

Having a small, close-knit campus was important for Turner. Living nearly 2,400 miles from friends and family, she thought it would be important to find “her community” right away.

Turner attended a “pretty diverse” high school in Alameda, California. Xavier’s campus has become more multicultural in recent decades, but it’s still a predominantly white institution or PWI.

Of the school’s roughly 4,600 undergrad students, about 24.8% are persons of color. Only 476 of those students, or 10.4%, identify as Black or African American, per data from Xavier University.

She recalled it being difficult to choose between Xavier or a historically Black college or university. She ultimately picked her soon-to-be alma mater because of its psychology program.

“I just felt drawn to Alpha Kappa Alpha Sorority, Inc.,” Turner said of her first impressions of the sorority.

She mentioned being impressed by the impact prophytes — members of the organization who initiated before her — have had on the community over the years. She also enjoys the social programs the sorority runs every year.

“I definitely found my community,” she added.

Meeting the "Divine Nine"

Besides Alpha Kappa Alpha Sorority, Inc., there’s also Delta Sigma Theta Sorority, Inc., Kappa Alpha Psi Fraternity, Inc., Omega Psi Phi Fraternity, Inc., Phi Beta Sigma Fraternity, Inc., Zeta Phi Beta Sorority, Inc., Sigma Gamma Rho Sorority, Inc., and Iota Phi Theta Fraternity, Inc.

The first Black fraternity was Alpha Phi Alpha Fraternity, Inc., founded in 1906 at Cornell University.

Black fraternities and sororities are guided by the principles and practices of their national chapters, said Anthony Milburn, an associate professor at Central State University. It’s a historical Black college or university near Dayton, Ohio.

But Milburn, a history professor, noted differences between Black fraternities and sororities and their white counterparts. Milburn joined Alpha Phi Alpha Fraternity, Inc., while studying at The Ohio State University.

The Black Greek-lettered organizations have a focus on promoting social justice both on their respective campuses and across the country. They take part in several educational, economic and public service activities throughout the year.

This year, Turner and her sorority sisters focused on issues such as supporting families and promoting economic success. She fondly recalled an event earlier this year where the group cooked meals for teens at a local runway shelter. They also talked to them about continuing their education.

Students don’t pledge new members to join the Divine Nine organizations, Milburn said. Instead, they’re engaged in a learning process, requiring a learning of the organization’s history and mission, he said, noting a student’s grades will often improve during the process.

“In my experience, Black fraternities and sororities are much more community focused; they’re much more in tune with public service to those communities,” he added. “And that’s whether you’re talking about a chapter at Central State, Wilberforce University, Ohio University, or Bowling Green State University.”

While Black Greek organizations operate similarly across their national chapters, their practical function for students who take part there may function slightly differently than those chapters at PWIs, such as Ohio State, Milburn said.

Most of the organizations were born in part of the 20th century, an era when Black people were denied basic rights and privileges.

Racial discrimination and isolation on predominantly white campuses created a need for Black students to stand together in solidarity and provide a cultural “safe space” for them to pursue education, Milburn said.

Cornell University — an Ivy League school in Ithaca, N.Y. — was one of a few major universities to allow Black students. But while they could attend classes, those students couldn’t live in campus housing because of social segregation.

Instead, Black students found lodging and community with local Black families, according to Cornell University. A group of Black students formed a literary society in one of these houses to create a support network for both academic and social success. It would later become Alpha Phi Alpha Fraternity, Inc.

Over the years, the fraternity has grown to roughly 900 chapters across the country, with membership that includes trailblazers such as Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr., W.E.B. Dubois and Thurgood Marshall.

Altogether, the council’s membership exceeds 1.5 million individuals around the world.

“The original goal was to provide a place where students of color could come together to discuss academics, talk about life and support each other through their educational journey,” Milburn said.

Creating brothers and sisters for life

To promote continued successes after graduation, the Divine Nine undergraduate organizations align with graduate chapters. Those groups have members like Sharon D. Howard, who remain involved after graduating.

That’s one of the big differences between Black Greek life and its white counterparts, said Howard, who graduated from the University of Dayton in 1978.

“Our involvement becomes even stronger once we graduate,” she said.

Today, there are more than 350,000 members of Alpha Kappa Alpha Sorority, Inc. across the globe. Howard described the large roster of alums as the equivalent of having sisters all over the planet.

Howard gave a hypothetical example of a sorority member losing their wallet during a trip to Las Vegas to describe the relationship between the sorority's members: "That person could go to the sorority directory, look up the local chapter, and would have women she’s never met doing what they can to help.”

The graduate chapters also serve as mentors to the young women and men who are on college campuses today.

“It doesn’t matter what age or where you went to school, because you’re all linked forever,” Howard said. “You have a band of sisters or brothers who can assist you with navigating a new journey in life.”

Howard chose UD because her father went to school there. She grew up and attended public school in West Dayton, a predominantly Black part of the city.

She praised UD for having a longstanding commitment to embracing cultural differences. But she was quick to note that the school’s student body wasn’t amazingly diverse, “especially back in the day.”

Being a self-described “natural extrovert” was a bonus for Howard as she adapted to her new surroundings. Fellow Black students who weren’t as naturally outgoing may have had more difficulties given what she referred to as “differentiators” between them and the predominantly white students, she said. She mentioned everything from religion to socioeconomic status.

Campus organizations, fraternities or otherwise, can make it easier to overcome that “initial shock” and make it to your second year, Howard said.

“That’s what the sorority did for me,” she added.

To Howard, the Divine Nine served as an opportunity to celebrate various facets of Black life. She noted “stepping” or a step show as being unique to Black Greek organizations.

While it’s “good, old-fashioned fun,” it’s rooted in African American cultural heritage, Howard said. Each sorority and fraternity have their own dances.

“It is creative, it’s expressive, and it’s our cultural,” Howard said.

Are Black fraternities and sororities still needed today?

Samuel Terry serves as the assistant director of Xavier’s Center for Diversity Inclusion. It oversees multicultural affairs on campus, such as the NPHC.

The office’s job, Terry said, is to create a campus environment where students of all backgrounds and cultures feel accepted.

He noted Xavier’s commitment to promoting diversity on campus through roughly 12 cultural organizations available to students.

Supporting diversity on campus is important because it provides a sense of belonging to students who aren’t represented broadly on campus.

Black fraternities and sororities still have an important place on college campuses, said Terry, a member of Alpha Phi Alpha Fraternity, Inc. He noted Black students still face unique obstacles compared to some of their peers.

Barriers to graduating from college for some African American students are evidenced by the relatively low retention rates of Black students across the nation, based on data presented by the United Negro College Fund. Among students enrolled in four-year public institutions, 45.9% of Black students complete their degrees in six years – the lowest rate compared to other races and ethnicities. Black men have the lowest completion rate at 40%.

Terry noted that, whether intentionally or not, minority students still to this day deal with microaggressions in classrooms and dorm rooms.

“We were founded in 1906, and we’re still fighting for the same injustices that were happening back then, so I don’t think our mission will ever change,” Terry said.

Looking back, Turner says she loved her time at Xavier. She’d probably still have gone to school there even if it didn’t have any Black sororities or fraternities, she said. But she stressed that being part of one has made her more confident to take on new things, such as running a campus-wide student organization.

“I’ve learned to never doubt or put limits on myself,” Turner said. “Alpha Kappa Alpha has definitely pushed me to strive for more.”