DAYTON, Ohio — Raúl Ordóñez has spent his career designing control systems for aerospace companies and the United States Air Force to help with airplane performance.

Now, he’s dedicating his decades of electrical engineering experience and understanding of data modeling to help improve system performance in a less science-minded area.

Homelessness.

What You Need To Know

- A new University of Dayton class aims to help Montgomery County tackle homelessness

- Engineering Systems for the Common Good is a new class offered by Raúl Ordóñez

- Engineering students are taking a deep dive into data to help the county analyze its approach to tacking on homelessness

- The class is part of UD's new human rights in engineering minor

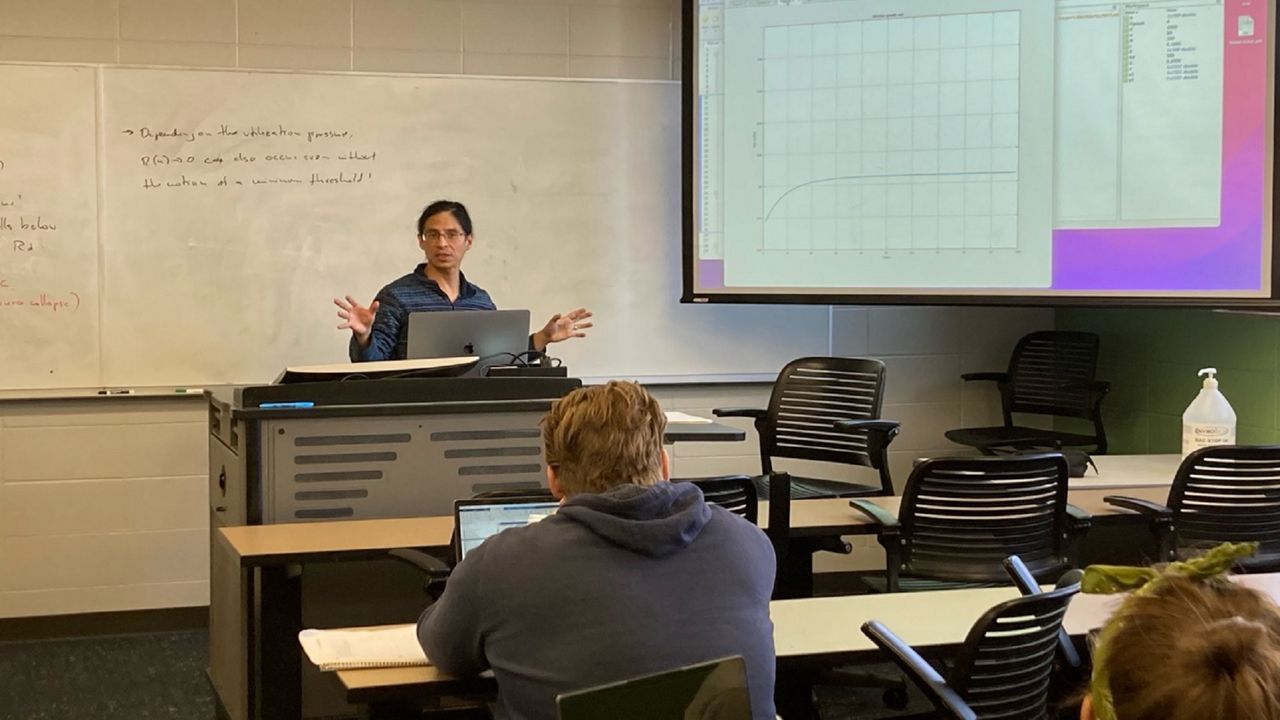

Ordóñez, a University of Dayton professor, is teaching a course this semester called Engineering Systems for the Common Good.

As part of their final project, students are using differential equations and statistical models to examine changes in the number of people experiencing homelessness in greater Dayton and analyze the reasons for it.

The class is part of a broader partnership on the issue between Ordóñez and Montgomery County Homeless Solutions.

“As the number of homeless people in Montgomery County changes with time, we can turn the data into a model,” said Ordóñez, a professor of electrical and computer engineering. “Then we’ll be able to see what factors influence different things, and how that changes when factors change.”

Diving deep into the data to help neighbors

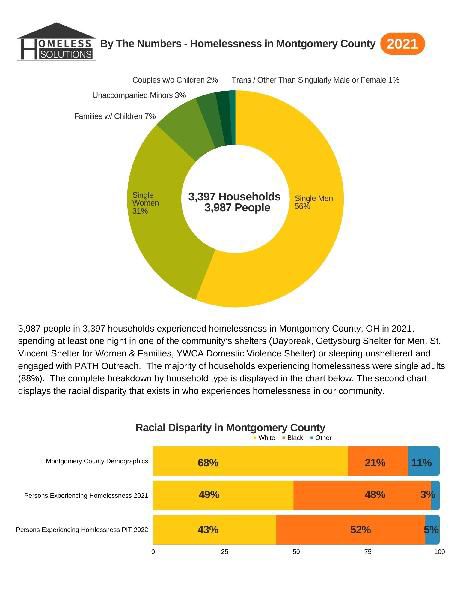

Nearly 4,000 people experienced homelessness in Montgomery County in 2021, spending at least one night in a community shelter or sleeping unsheltered, according to Montgomery County Homeless Solutions.

About 7% of those experiencing homelessness last year were families, per the data, while unaccompanied minors made up roughly 3% of the group.

Numbers across the county have actually been down the past few years, according to Kathleen Shanahan, homeless solutions program coordinator at Montgomery County. She attributed that to pandemic-related programs such as rental and mortgage funding, and moratoriums on evictions.

Now that those programs are ending, she predicts homelessness numbers to be back closer to pre-pandemic levels this year.

The use of data has grown since she began working in planning and coordination of homelessness resources in the mid-1990s, Shanahan said. But her staff doesn’t have the capacity or the technical ability to analyze it properly.

This semester alone, Ordóñez and his students are tackling 10 years’ worth of data to help the county better target its prevention resources and evaluate its housing intervention strategies.

“In a nutshell, this class will allow us to better understand our data and analyze it in a way that we don’t have the capacity to do here,” Shanahan added.

For this year, Shanahan’s expectations are modest. But long-term, she envisions being able to use the findings to identify trends or disparities in the system. She gave an example of analyzing the effects of deploying more targeted resources to families with children.

“I think it really has a lot of potential to help us look at data differently and develop alternative approaches to homelessness,” Shanahan added.

Creating students who create change

The course is an elective for fourth-year engineering students or any UD student who has the minimum required mathematical background in differential equations.

The semester’s class has seven students – five undergraduates, a graduate student in engineering management and an electrical engineering student who’s auditing the course.

One of those students is Noah Blum, 22, a computer engineering major. He called taking this class a “no brainer” after having Ordóñez last semester for a control systems course.

“At first, approaching social issues as an engineering problem was a little strange to me, but the approach definitely applies to everything,” Blum said. He chuckled while recalling the regularity with which Ordóñez reminds his class that “everything can be modeled with a control system.”

Questions the class is pondering to close out the fall semester include: What would it take to end chronic homelessness? How many are reusing services multiple times? And how many of them find a permanent home?

Ordóñez’s inspiration for the class came from two places: growing up seeing sweeping poverty in his native Ecuador and regular conversations over the years with his wife, Susanne, a UD law student.

The goal is to find a “way to use systems theory and mathematical models to address social problems,” Ordóñez said. He got that chance when UD’s School of Engineering created a human rights in engineering minor this year.

Ordóñez hopes the new program leads to not only more classes but expanded relationships between UD, the city of Dayton and Montgomery County. There’s also room for expanded growth between the School of Engineering and the Human Rights Program on the other side of campus, he said.

It’s not just about finding solutions to individual problems, Ordóñez feels. It’s about changing the way engineers approach their work.

Ordóñez wants his students in his class to see what they learn as engineers goes well beyond engineering. He wants them to gain a perspective that they have an “arsenal of skills and the ability to do more than ‘make better phones.’”

At least one of his students is already taking note.

“This semester is helping me to not only think about the social aspects when I’m doing something with engineering, but it’s also helping me realize the importance of addressing social issues from an engineer’s perspective,” Blum said.