CLEVELAND — University Hospitals Harrington Heart & Vascular Institute's new study further proves those who faced housing discrimination decades ago suffer higher rates or poor health outcomes.

The findings were published in the Journal of the American College of Cardiology.

The poor health outcomes include heart disease, kidney failure and diabetes.

The federal government created the Home Owners' Loan Corporation in the 1930s to stabilize the housing market during the Great Depression. The HOLC also offered home mortgage refinance services to some homeowners in default and to expand home buying opportunities for some citizens.

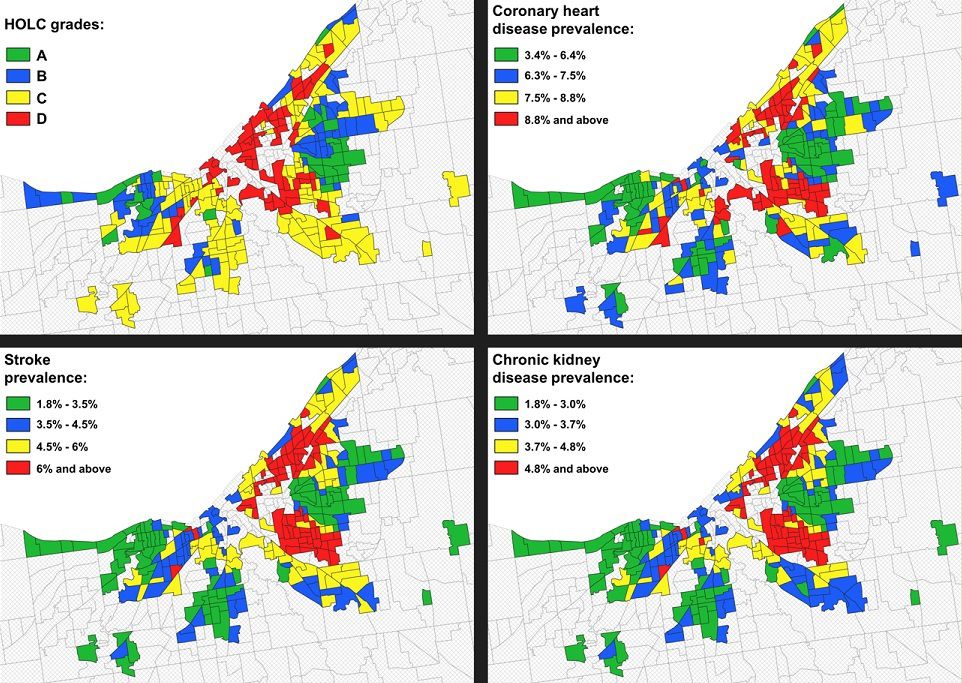

There were nearly 200 U.S. cities mapped by the HOLC to denote potential lending risk: A (“best” or green), B (“still desirable” or blue), C (“definitely declining” or yellow) and D (“hazardous” or red), with the latter deemed as a “redlined” neighborhood.

Majority Black neighborhoods were more often "redlined," which meant people living there were more likely to be denied a loan to buy or renovate homes. The practice was not outlawed until the 1960s.

“Earlier studies have shown that Black adults living in previously redlined areas had a lower cardiovascular health score than Black adults living in neighborhoods given a grade of A,” said Dr. Sadeer Al-Kindi, cardiologist at UH Harrington Heart & Vascular Institute and co-author of the study. “Our study is the first to examine the national relationship between redlined neighborhoods and cardiovascular diseases. It supports the results of previous related studies while additionally showing that historic redlining is associated with an increased risk of comorbidities and a lack of access to appropriate medical care today.”

The study linked 1930s redlining maps with current neighborhood maps to examine the prevalence of cardiovascular risk factors and disease obtained through the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention data. They were ranked by neighborhood category (A through D, A meaning "lowest risk" and D meaning "highest risk").

More than 11,000 HOLC-graded census tracks and 38.5 million people across the country were included in the study.

The results show an overall increase in rates of obesity, diabetes, high blood pressure, and smoking across the grading spectrum from A to D.

Nearly twice the amount of adults between the ages of 18 and 64 did not have health insurance in D-graded areas compared to those in A-graded locations. Neighborhoods with a better grade had more routine health visits and better cholesterol screening as compared to neighborhoods with a worse grade.

“Our group at UH Harrington Heart & Vascular Institute wanted to study redlining in this way to better understand the socio-environmental underpinning of health inequities. Such understanding can provide unprecedented new information with which one can attempt to solve the current epidemic in chronic non-communicable diseases,” said Dr. Sanjay Rajagopalan, chief of the Division of Cardiovascular Medicine and Chief Academic and Scientific Officer of UH Harrington Heart & Vascular Institute.

Rajagopalan is also the Herman K. Hellerstein, MD, Chair in Cardiovascular Research.

“UH is committed to improving the health of all people in Northeast Ohio by advancing science and human health and this study provides a foundation for programs like ACHIEVE GreatER,” Rajagopalan said.

ACHIEVE GreatER, announced last year, is an initiative funded by a transformative $18.2 million grant from the National Institutes of Health. Through the initiative, University Hospitals will provide care to those living in the Cuyahoga Metropolitan Housing Authority. More than half of the Metropolitan Housing Authority units fall into a previously redlined category.

“ACHIEVE GreatER has an ultimate goal of reducing cardiovascular complications and hospitalizations by improving blood pressure, lipids and glucose targets for Black patients at risk of heart health issues,” said Dr. Rajagopalan, who is also the principal investigator of Cleveland’s ACHIEVE GreatER team.

Health workers will go into the communities to provide personalized health advice, such as diet and exercise, and services including screenings for blood pressure, cholesterol and average blood sugar.

“The mission of University Hospitals is to heal, to teach and to discover. With our redlining study, we have confirmed a problem that needs addressed. Now, armed with this crucial information, we have an opportunity to heal and a duty to act,” said Dr. Mehdi Shishehbor, president of UH Harrington Heart & Vascular Institute, and Angela and James Hambrick Chair in Innovation.